Aside from ethical questions, the logic of a private entity opening an offshore company seems elementary —to declare its profits in a territory where it can pay less tax than it should in its place of origin. But when it comes to a state-owned company like Petróleos de Venezuela, which is not obliged to pay taxes - and therefore does not need to evade them - it is difficult to understand why within its business scheme there is contracting with companies established in tax havens and there is even the creation of their own subsidiaries in these places. What does the Venezuelan public treasury gain from this?

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

"Managing and operating alone or in conjunction with other corporations, individuals or companies all types of facilities, refineries, terminals, pipelines, ports, jetties or quays for the transportation, handling, processing, refining and storage of oil, gas, coal, oils and fuels of all kinds, lubricants and hydrocarbons of any kind and all sorts of products or byproducts and liquids in general."

As the metaphor of that player who is fourth bat, catcher and boyfriend of the godmother of the team, the previous paragraph is just the first of eight objectives set by company Pdvsa Marketing Internacional (Aruba) AVV, established on that Caribbean island with a capital of $ 30,000, more than a modest amount for the pretensions of also issuing and buying bonds, participate in the liquidation of companies or participate in "all types of contracts with legal purpose". This is stated in the company's articles of incorporation, one of the 13.4 million documents obtained in a leak of the Appleby law firm by the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung and shared by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalism, better known as Paradise Papers.

The document states that the company was incorporated on July 22, 1991, and was relaunched in 2009 with the signatures of Asdrúbal Chávez -then vice president of Trade and Supplies of Pdvsa and current president of Citgo- and Eudomario Carruyo, then vice president of finance of the state oil company, fallen in disgrace after being blamed for participating in the diversion of resources that ended with the Pension Fund of the company. Although there are no clear signs to notice if the company made any contract through that Aruban branch and from which it does not leave a formal registration anywhere, the organization of this company in a tax haven is far from being an isolated practice in the times of the “redder than red” PDVSA.

Also in 2009, Pdvsa Gas contracted the services of the Appleby law firm for the incorporation of company Pdvsa Gas Accro Ltd - replacing another company known as Accroven Holdings Ltd - which was registered in Barbados in September of that year with a wide range of objectives and more ambitious purposes related to gas exploitation.

In 2010, Ricardo Coronado, the then general manager of the PDVSA Offshore Division, signed the as the sole director. After climbing high positions within the industry, he was accused of corruption by the Comptroller's Office Committee of the National Assembly and left the country long before the raid that now has directors like Eulogio del Pino and Nelson Martínez, among 63 other workers of the company, behind bars.

Although Pdvsa Gas's finance department did not officially respond to a questionnaire about the scope and operation of that company, not specified in any management report, a source from the oil company confirmed that the office is active, but did not specify the nature of its activities.

Why a State-Owned Company Opens Offices in a Tax Haven?

The leak of law firm Appleby also reveals that company WillPro Energy Services (Pigap II) was acquired by Pdvsa Gas - specialized in gas injection and compression services - for 112.4 million dollars, which is registered in the Cayman Islands, although it has an established office in Maturín, state of Monagas. Many unsuccessful attempts were made to establish a telephone contact with that branch.

Why a state-owned company opens offices in a tax haven? After clarifying the point that PDVSA has no need to evade taxes in Venezuela, a lawyer experienced in the organization of financial entities and offshore companies assured Armando.info that the first explanation can be found in the exchange control in force in Venezuela since 2003 and the possibility offered by these companies to have a business relationship with the oil company without passing through that control.

"The payments in US dollars received by an offshore company, even from Pdvsa, do not have to pass through the Central Bank of Venezuela," specifies the expert referring to the amendment to the BCV Law that released Pdvsa from the obligation to pass all its profits to this entity. "This made it easier to place foreign exchange in other places like Fonden or offshore companies."

The basic problem with these placements is their lack of transparency. Being out of Venezuelan jurisdiction, the Venezuelan Office of the Comptroller or the National Assembly can hardly ask for any accountability, especially if Pdvsa does not make these companies public. In its official organization chart, the state company only recognizes PDV Insurance Company (Pdvic) as the only company established in Bermuda.

"The ought-to-be is that Pdvsa does not have intermediaries and contracts directly, so that the companies can be duly audited"

The other relevant point is that by organizing subsidiaries in tax havens, Petróleos de Venezuela has the possibility of subcontracting without going through the bidding process established in Venezuelan laws. "The offshore company can, by nature, receive payments and also pay to any supplier practically without controls. If it is an offshore that is managed as a Pdvsa subsidiary, the bidding is also avoided because it is the company itself acquiring a good or service from a subsidiary. It does not mean that this happens, but it gives room to all kinds of subcontracting, surcharge and collection of commission."

An example of these uncontrolled management was what Pdvsa Insurance Company (Pdvic) did by giving 66.7 million dollars to a financial fund –Fractal Fund Management– that ended up entangled in the Ponzi scheme in which over 500 million dollars of the state oil company were lost. "The ought-to-be is that Pdvsa does not have intermediaries and contracts directly, so that the companies can be duly audited," concludes the lawyer.

The number and broadness of the objectives established by these companies in their articles of incorporation also contributes to the possibility of making all kind of contracting with any type of company. Tax havens allow these lax definitions to facilitate the establishment of companies, unlike the laws of other countries, including Venezuela, which order more specific definitions.

Another well-known case of a detrimental subcontracting for the Venezuelan public treasury was the lease of the Aban Pearl platform from offshore company Petromarine Energy Services Ltd, registered in Barbados. The platform, which collapsed on April 13, 2010, was contracted with a surcharge of up to 50 million dollars, according to the complaint filed by the Commission of the Comptroller's Office of the National Assembly with the Venezuelan Prosecutor's Office.

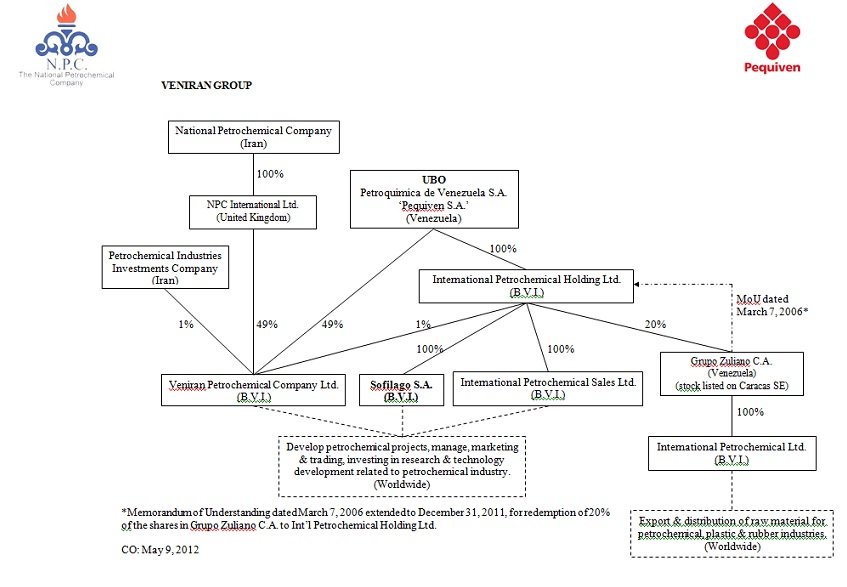

With the first leak of documents known as Panama Papers - that time from the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca– it was learned that Pdvsa’s liking for offshore companies was enough to create the joint venture Veniran Petrochemical Company in August 2007 between the Corporación Petroquímica de Venezuela (Pequiven) and its Iranian counterpart, National Petrochemical Company, then registered in the British Virgin Islands.

The prosecutor imposed by the Constituent, Tarek William Saab, reported this week the contracting of Pdvsa with company Petrosaudi Oil Services, which he qualified as a company without experience in offshore drilling, based in Barbados, without giving details about the potential loss for the Venezuelan state for contracting that company.

However, in the Paradise Papers there is proof that Pdvsa, through Petrosaudi Oil Services (Venezuela) Ltd, signed two drilling contracts, one, in October 2007, for 120 million dollars, which they called Neptune Drilling Contract; and the other, in September 2010, for 130 million dollars, which they called Saturn Drilling Contract.

Another leak shows that Pdvsa formed a joint venture (Petrolera Güiria) to exploit crude oil and gas in the Gulf of Paria together with the Italian oil company ENI and an offshore company called Ine Paria - previously called EOG Resources Venezuela Ltd -, registered in the Cayman Islands and with an office in Caracas. With the same company, it also created another joint venture (Petroparia) with the participation of the Chinese state company Sinopec. The then president of the Venezuelan Petroleum Corporation, Eulogio del Pino, who until a week ago was the "strong man" of Pdvsa, signed the papers of those companies on behalf of Venezuela.

Although the legality in the organization of these companies is not under discussion, Pdvsa does not give an official account of its relationship with most of them and, in some cases -as Pdvsa Gas Accro Ltd, PDVSA Marketing International (Aruba) AVV-, it does not even mention them in their management reports, much less the type of operations they do or the cost they represent to the State. So far, the only contribution of Pdvsa’s acquired liking in contracting offshore companies is the thickening of the veil of its operations.

Adrián Perdomo Mata has just entered the list of sanctioned entities of the US Department of the Treasury, as president of Minerven, the state company in charge of exploring, exporting and processing precious metals, particularly gold from the Guayana mines. His arrival in office coincided with the boom in exports of Venezuelan gold to new destinations, like Turkey, to finance food imports. Behind these secretive operations is the shadow of Alex Saab and Álvaro Pulido, the main beneficiaries of the sales of food for the Local Supply and Production Committee (Clap). Perdomo worked with them before Nicolás Maduro placed him in charge of the Venezuelan gold.

Gassan Salama, a Palestinian-cause activist, born in Colombia and naturalized Panamanian, frequently posts messages supporting the Cuban and Bolivarian revolutions on his social media accounts. But that leaning is not the main sign to doubt his impartiality as an observer of the elections in Venezuela, a role he played in the contested elections whereby Nicolás Maduro ratified himself as president. In fact, Salama, an entrepreneur and politician who has carried out controversial searches for submarine wrecks in Caribbean waters, found his true treasure in the main social aid and control program of Chavismo, the Clap, for which he receives millions of euros.

While the key role of Colombian entrepreneurs Alex Saab Morán and Álvaro Pulido Vargas in the import scheme of Nicolás Maduro’s Government program has come to light, almost nothing has been said about the participation of the traders who act as suppliers from Mexico. These are economic groups that, even before doing business with Venezuela, were not alien to public controversy.

Even though there are new brands, a new physical-chemical analysis requested by Armando.Info to UCV researchers shows that the milk powder currently distributed through the Venezuelan Government's food aid program, still has poor nutritional performance that jeopardizes the health of those who consume it. In the meantime, a mysterious supplier manages to monopolize the increasing imports and sales from Mexico to Venezuela.

Turkey and the coastal emirates of the Arabian Peninsula are now the homes of companies that supply the main social -and clientelist- program of the Government of Venezuela. Although the move from Mexico and Hong Kong, seems geographically epic, the companies has not changed hands. They are still owned by Colombian entrepreneurs Alex Nain Saab Morán and Álvaro Pulido Vargas, who control since 2016 a good part of the Import of food financed with public funds. Around the world for a business.

Since its opening in 2017, the Porsche Design Tower quickly became a symbol of luxury and ostentation in South Florida. Magnates from all over the world retreat behind the discretion of its tinted glass windows and virtually anonymous legal entities. But in recent days, two police investigations into illegal financial flows from abroad placed the building under an inconvenient spotlight. The justice just seized an apartment of over five million dollars from a Venezuelan agent.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.