With ridiculous fines and a brief freezing of accounts, Mexican authorities said they had sanctioned in 2018 the companies of that country that participated in the million-dollar scheme that supplied products to Clap boxes, including those that sold milk powder of poor nutritional quality. With Alex Saab - architect and head of these operations- arrested in Cape Verde three weeks ago, the irregularities of an investigation that seemed to have done justice in Mexico begin to be revealed. In the end, it was a punishment that neither hurt nor compensated anyone.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Echoes of Alex Saab’s arrest reach several places from Cape Verde, where he was captured on June 12, following the activation of an Interpol red alert. First, Venezuela, his business center for almost a decade, and then, Colombia, where he was born and where his political connections and a trial against him are now reviving. The shock is also being felt in Mexico. Since 2016, Mexico has been a key country for Saab and his Colombian partner, Alvaro Pulido Vargas, in the million-dollar food supply scheme for the Local Supply and Production Committees (Clap) program that Nicolas Maduro’s government set up in Venezuela that year.

Mexican authorities are investigating the operations of Saab and Pulido since 2018, at the end of the administration of former president Enrique Peña Nieto. Although at the time they made accusations against the scheme developed by the Colombian businessmen, everything was diluted in a bureaucratic limbo. But the shake-up caused by the arrest of Alex Saab, now makes it possible to reveal the weaknesses of that investigation, which in practice, did not only absolve Saab’s and Pulido’s companies, but also the Mexican suppliers who shipped to Venezuela products of very low nutritional quality.

The behind-the-scenes of that process is a story of omissions and silences that shows how Mexican and Venezuelan authorities knew for months about the poor quality of the merchandise, but did nothing to stop that questionable trade and even relieved those responsible of any punishment.

On October 18, 2018, the Attorney General’s Office of Mexico, reported through Israel Lira - the deputy attorney general specialized in organized crime investigation - that food exports to Venezuela were being made through a “fraudulent scheme” with “unusual operations” and “low quality” products with “overpricing.”

The official pointed directly at Group Grand Limited, the Hong Kong-based shell company that Saab and Pulido control, and a company with the same name in Mexico, run by relatives and operators of the Colombian tandem, as well as the network of suppliers with which they entered into contracts. Despite the seriousness of the allegations and some initial measures, like the freezing of bank accounts, the same official opened the door to a “reparatory agreement” with those involved, by way of compensation.

“The accused will hand over to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) the amount of three million dollars, approximately 56 million pesos, which will be allocated to maintain the mandate of UNHCR in Latin America and the Caribbean,” Lira said at the time.

The shadow of the irregularity always surrounded that “reparatory agreement,” and the amount of the penalty seemed ridiculous for a business where hundreds of millions of dollars had been moved. Today, Santiago Nieto, head of Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), describes it as an “unusual event.”

“The businessmen and individuals charged made a reparatory agreement with the Attorney General’s Office that is illegal, because despite the existence of an irregularity of 156 million dollars, they were imposed a donation of only three million dollars (...) Instead of this money being deposited in an account of the Treasury of the Federation (Tesofe), as it happens in this type of cases, it went to the office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). We already reported this to the Ministry of Public Administration and to the Prosecutor’s Office,” Nieto explained to Claudia Solera, a reporter of the Excelsior daily newspaper in Mexico City and coauthor of this report.

Other documents prove the illegality and the flaws of the agreement with the companies operated by Alex Saab and Alvaro Pulido, as well as their Mexican suppliers.

By the time the Mexican Attorney General’s Office made both the complaint and the corresponding “reparatory agreement” public, there was plenty of evidence about the anomalies and the actors around the export scheme. Armando.Info had revealed the participation of Saab and Pulido in Group Grand Limited and, in February 2018, documented the poor nutritional quality of the Mexican milk powder that arrived with the CLAP boxes through a laboratory analysis of samples of the different brands of milk, conducted by the Institute of Food Science and Technology of Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV).

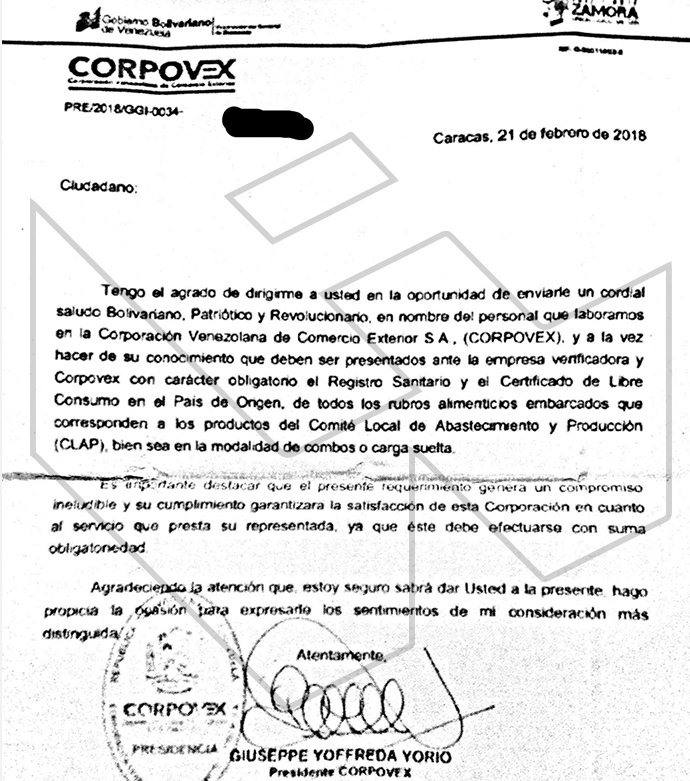

Shortly thereafter, the Venezuelan state-owned company Corpovex, in charge of centralizing public imports, asked the Mexican companies to comply with sanitary registries. The Venezuelan prosecutor in exile, Luisa Ortega Diaz, had said in August 2017 that Group Grand Limited “presumably belongs to the president of the Republic,” referring to Maduro.

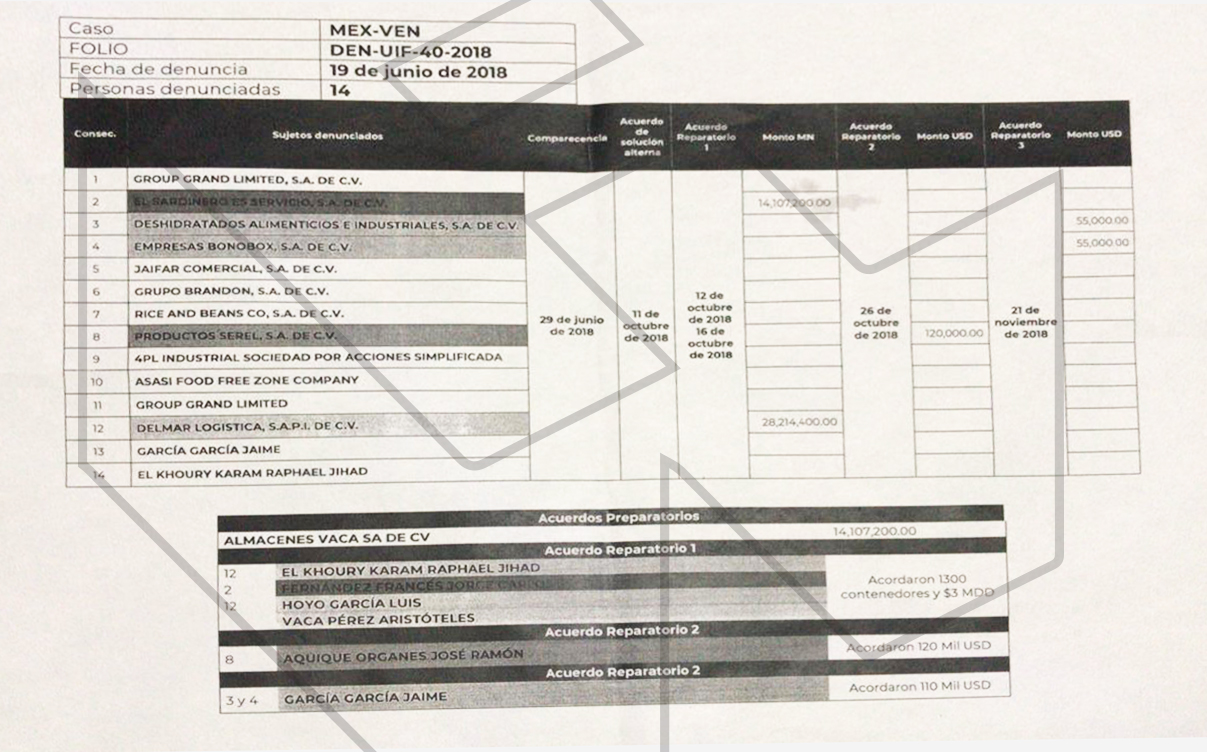

It is now known that the investigation that led to that pronouncement by Mexican authorities in October 2018, began in June of that year. At that time, the Financial Intelligence Unit filed complaint DEN-UIF-40-2018 to the Mexican Attorney General’s Office and the Ministry of Public Administration.

In addition to Group Grand Limited, the company controlled by Alex Saab and Alvaro Pulido, the brief listed Mexican companies, such as, El Sardinero, Deshidratados Alimenticios e Industriales (DAI), Empresas Bonobox, Jaifar Comercial, Grupo Brandon, Rice & Beans and Productos Serel. The list also included Asasi Food FZC, a company registered in the United Arab Emirates and also used by Saab and Pulido, and 4PL Industrial, a Colombian company that provides logistics and product packaging for the Claps, also linked to the Saab-Pulido duo. The complaint also included the names of Mexican businessmen Jaime Garcia and Raphael Jihad El Khoury Karam.

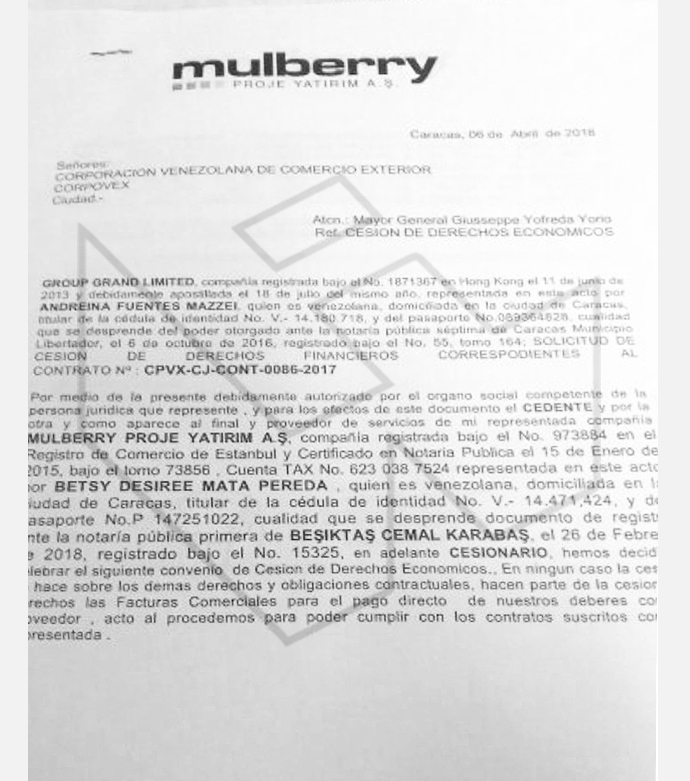

In April 2018, days before the disputed presidential election in which Maduro secured re-election, owners and executives of these companies had met with Alvaro Pulido Vargas at Madrid’s luxurious Hotel Villa Magna to expedite the deal. Suspicions against Group Grand Limited forced the Colombian businessmen to replace that company with Asasi Food FZC, registered in the United Arab Emirates―whereby they obtained a contract for 345 million Euros in 2018―and Mulberry Proje Yatirim, a Turkish company.

Indeed, in a letter dated April 2018, Group Grand Limited proposed to Corpovex - the state-owned company that signed the contracts with Claps intermediaries - the “transfer of the financial rights corresponding to contract CPVX-CJ-CONT-0086-2017” to the Turkish company Mulberry Proje Yatirim. This agreement amounted to almost 426 million dollars and was the second one achieved by Group Grand Limited for the Claps. The first one, for 340 million dollars, was signed in late 2016 through the State Government of Tachira, with Jose Vielma Mora in office.

Group Grand Limited, as well as Asasi Food FZC and Mulberry Proje Yatirim, in addition to Alex Saab and Alvaro Pulido themselves, were sanctioned by the U.S. Department of the Treasury in July 2019. “Several companies Saab and Pulido own or control were used in Saab and Pulido’s food corruption scheme,” the Treasury said in a statement.

Almost simultaneously, a Florida state court charged them for money laundering in connection with the first deal they struck with Chavismo in 2011 for the construction of prefabricated homes.

But authorities in Mexico, contrary to those in the United States, did not criminalize Saab’s and Pulido’s scheme. They simply opened the door to “reparatory agreements” that seem to be custom-made for the offenders.

For months, company El Sardinero was the main supplier of the Clap boxes that left the port of Veracruz in Mexico to the port of La Guaira, on the vessels named CNP Paita and Viking Merlin. Rice & Beans and Productos Serel also supplied their products, such as rice and lentils, while Grupo Brandon, a company with a very diffuse trace in the state of Nuevo Leon, virtually monopolized the shipments of milk powder with different brands of very poor nutritional quality.

The first reparatory agreement was completed on October 12, 2018. Each representative of El Sardinero, Delmar Logistica, Almacenes Vaca and Rice & Beans paid $ 750,000 for a total of $3 million that would go to UNHCR, announced by the Attorney General’s Office of Mexico a few days later. In addition, they promised to hand over to the authorities 1,300 containers with about two million Clap combos.

Santiago Nieto, current head of Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit, highlights several flaws in the resolution. “First, these three million dollars should not have been deposited to the UNHCR, as a penalty, but to the Tesofe, as provided for in the Code of Criminal Procedures in the event of a reparatory agreement. It should be so by law. It is also illegal to agree the confiscation of 1,300 containers, later sent to Venezuela, when one of the irregularities had been indeed the acquisition of these low quality nutritional foods.”

The businessmen, for their part, claim to have complied with the authorities’ demands at the time. For instance, regarding El Sardinero, they insist that they honored the “reparatory agreement,” as they paid the donation, paralyzed their business with Venezuela and delivered the two million Clap boxes to the Mexican Foreign Ministry.

But that was not the only “reparatory agreement.” On October 16, 2018, the Attorney General’s Office of Mexico agreed with representatives of the Kosmos group ―the products of which, namely Productos Serel and La Cosmopolitana, were also included in the Claps― to impose a fine of just $120,000, which they also had to pay to UNHCR. For example, Kosland milk powder was one of the products of Productos Serel and among those with the worst nutritional values. The penalty is insignificant considering that, according to the Mexican Financial Intelligence Unit, Productos Serel sold merchandise for several million dollars to Wellsford Trading Corp, another intermediary contracted by the Maduro government.

Wellsford Trading Corp, registered in Panama, signed on March 30, 2017, contract 0032 for almost $70 million with the state-owned Corpovex.

A third “reparatory agreement" was sealed on October 26, 2018. It was agreed upon with company Almacenes Vaca, on which a fine of just over 14 million pesos was imposed, equivalent to some $700,000, also payable to UNHCR. The owner of this company also owns Rice & Beans, another of the main Clap suppliers from 2017 to 2018. Just a single invoice of July 2018 shows that Rice & Beans charged Mulberry Proje Yatirim - the Turkish company, whereby Alex Saab and Alvaro Pulido replaced Group Grand Limited - $220,000 dollars for products.

The fourth “reparatory agreement” was signed on November 21, 2018. In this case, the authorities agreed a fine of $110,000 with the representative of companies Jaifar Comercial, Delmar Logistica and Empresas Bonobox, which at some point participated in the logistics for the Clap from Mexico.

But if the criteria of the “reparatory agreements” are now questioned by the head of the Mexican Financial Intelligence Unit, even stranger is that Group Grand Limited, the company used in Mexico by Alex Saab and Alvaro Pulido, has managed to recover their bank accounts after authorities ordered to freeze them.

Two years after the investigation started in Mexico, only three companies remain blocked in the financial system of that country: Grupo Brandon, Group Grand Limited Hong Kong and Group Grand Limited Mexico. However, the company managed by Saab and Pulido won in November 2019 an injunction against the Financial Intelligence Unit, thus, it could unfreeze two bank accounts in Scotiabank Inverlat.

The document that justified the decision states that under “Article 115 of the Law on Credit Institutions, the bloking only applies to commercial agreements represented by the Mexican State and in the case of the food pantries, the negotiations were made between private companies. Paradoxically, the Venezuelan government now describes Alex Saab as a “government agent” for the purchase of food and medicine, and even claims “diplomatic immunity” for him.

“The main problems that we have faced in Mexico regarding the case of the Clap pantries are, first, the illegal reparatory agreement established with the businessmen by the Attorney General’s Office of the previous administration, led by Alberto Elias Beltran, and, second, the case-law that former minister Eduardo Medina Mora promoted to avoid that there was a freezing of accounts by the FIU, in which it is established, that if there is no application of international nature, there is the possibility of unfreezing the accounts. And although there is an international application, the judges granted the injunction,” as censured by the head of the Financial Intelligence Unit.

The accounts of Group Grand Limited were initially blocked on October 5, 2018, after the suspicion of operations with funds from illegal sources. One of the company’s representatives in Mexico, Andres Leon Rodriguez, filed a petition for injunction against the measure. After a legal battle between the company and the authorities, the accounts were finally unblocked in November 2019.

Other companies that were reported by Mexican authorities for their participation in the Clap plot, such as Ilas Mexico, B-Eminet, Digrava and Evaporadora y Secadora de Leches are near to achieve a measure similar to the one that benefited Group Grand Limited. Another proof that the investigation in Mexico fell into oblivion and that there were hardly any responsible for the accusations made in October 2018. With the apprehension of Alex Saab, the Mexican Financial Intelligence Unit seems ready to resume what it began two years ago and delve into the suspicious trail that the millionaire Clap business left in that country.

This is a work investigated and published simultaneously by Armando.Info and the Excelsior de Mexico newspaper.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.