An important ‘cold case' of high finance under Chavism can finally be solved thanks to the revelations arising out of the recent intervention in Curacao of Banco del Orinoco N.V., one of the jewels of the financial empire of the tycoon from Barinas ―the failed purchase in 2015 of Televen, one of the main private TV channels [in Venezuela]. This risky adventure left Vargas owing money to a somewhat questionable creditor. After delays and pressure, the banker had to dip into the turnover of his oil companies to get out of the difficulty.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

In September 2019, Banco del Orinoco N.V. was taken over by authorities in Curacao, the island nation 50 km (15 mi) off the coast of Venezuela that, like its former Dutch metropolis, maintains a status close to a tax haven. It was the closing act for the quarter-century history of the bank, registered in 1994. Its fall brought down other pieces of the offshore financial empire of Venezuelan magnate Victor Vargas, of which it was the cornerstone. Allbank of Panama and BOI Bank of Antigua, which shared accounts with each other and by which the same flow of funds circulated, collapsed within days.

Although it was not until September 2 that the Central Bank of Curacao and Sint Maarten decided to withdraw Banco del Orinoco’s operating license, by June 2019, it had warned the management of the bank that a final sanction was to be imposed in light of the evidence found on illegal management and chronic insolvency.

Long before that, at least since 2015, there had been rumors in the financial circles about the rich interest rates that Banco del Orinoco in Curacao was offering as a return to those who made placements in dollars, particularly wealthy clients of B.O.D. (Banco Occidental de Descuento) ―Vargas’ bank in Venezuela, also taken over by the National Superintendence in September 2019. It was about the ongoing effort by Vargas and his team to fill a hole in their balance sheets, dragged out for years; an effort that ended up resembling a pyramid scheme. As a result, when it fell apart, the funds of many Venezuelan investors, who never managed to redeem their CDs (certificates of deposit), or did so partially, got trapped in the bank’s files and in the evaporated money.Even so, the collapse left a crack open to see the bowels of a financial circuit that inflated like a soap bubble throughout the revolutionary period in Venezuela, up to a point that some media, especially Spanish media, did not hesitate to style Vargas as Chavez’s banker.

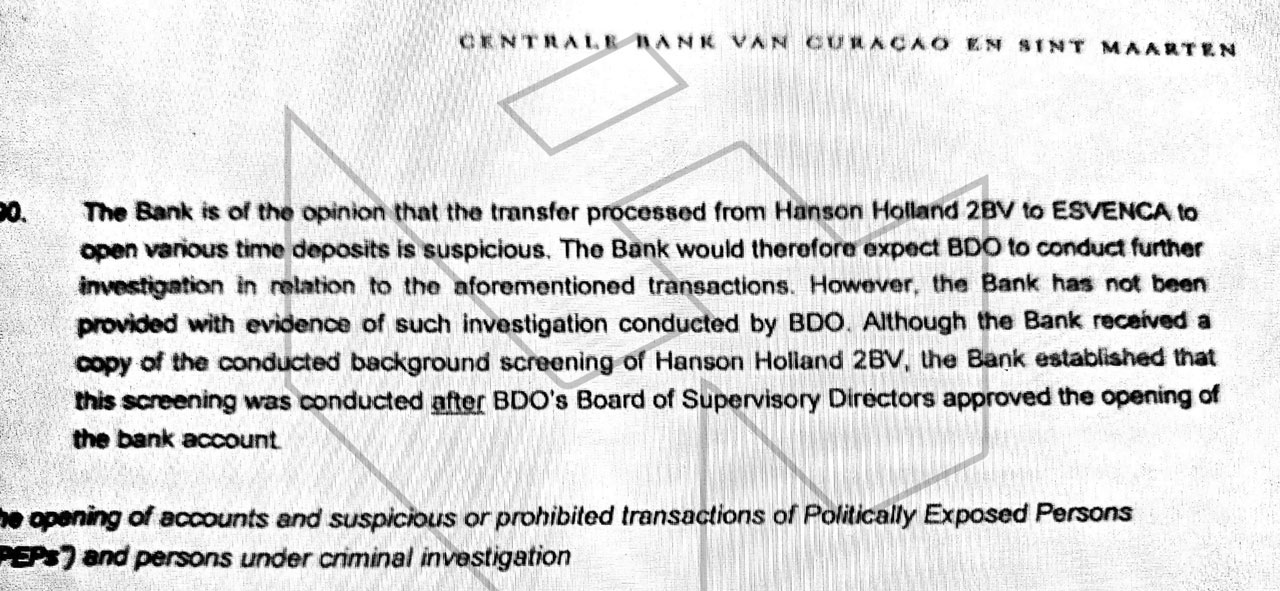

The report of the Central Bank of Curacao and Sint Maarten, where the regulator justified the closure of the business, refers to a bank account that received preferential and irregular treatment from Banco del Orinoco, “In the opinion of the bank [Central Bank of Curacao, N. de R.], the transfer processed from Hanson Holland 2 B.V. to Esvenca to open several time deposits is suspicious (...) Although the Bank received a copy of the background investigation conducted on Hanson Holland 2 B.V., it established that this assessment was made after the Board of Supervisory Directors of BDO [Banco del Orinoco, N. de R.] approved the opening of the bank account.”

Actually, the reference to Hanson Holland 2 and Esvenca, in addition to three documents on file in a notary office in Caracas, which Armando.info recently had access to, shed light afterwards on Victor Vargas’ relationship with a mysterious investor, presumably a powerful man of the Venezuelan regime, and on that investor’s frustrated attempt in 2015 to buy Televen, the country’s second private television channel.

What could be the most talked about and repeated quote of Victor Vargas in the media, although he is not very prone to give statements to the press, dates from 2008. Back then, he boasted to The Wall Street Journal by claiming, “I’ve been rich all my life.” Although shocking, the phrase then sought to persuade the reporter that his wealth was due neither to his alleged closeness to Chavez―although in the same interview he defined himself as “a socialist in the true sense of the word”―nor to his morganatic marriage to the daughter of banker Hector Santaella, Carmen Leonor, in 1976 (from whom he got divorced in 2013). Instead, he claimed an almost blood right to belong to the aristocracy, something he literally fulfilled in 2004, when his daughter, Maria Margarita, married Luis Alfonso de Borbon, Duke of Anjou, great-grandson of the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco and heir, according to the monarchists, to the Crown of France. The offering was reciprocal ―from that same day, Luis Alfonso became a director of B.O.D., of Allbank and of Banco del Orinoco itself, among other accounts of his father-in-law’s corporate string.

But Victor Jose de Jesus Vargas Irausquin made money from more plebeian files. He was born 68 years ago in Barinas, the Venezuelan Plains province, also the birthplace of Hugo Chavez. In the 1980s, he founded Banco Barinas and Grupo Financiero Cordillera, with imposing headquarters in the area of La Castellana, in northeastern Caracas. But the 1994 financial crisis wiped the bank off the map. Paradoxically, the collapse of his brand had the effect of a catapult for Vargas. On that same year, he bought the majority stake of Banco Occidental de Descuento (B.O.D.), a dominant entity, yet with little national projection, in the state of Zulia―the northwestern tip of Venezuela, home to the country’s oldest oil basin.

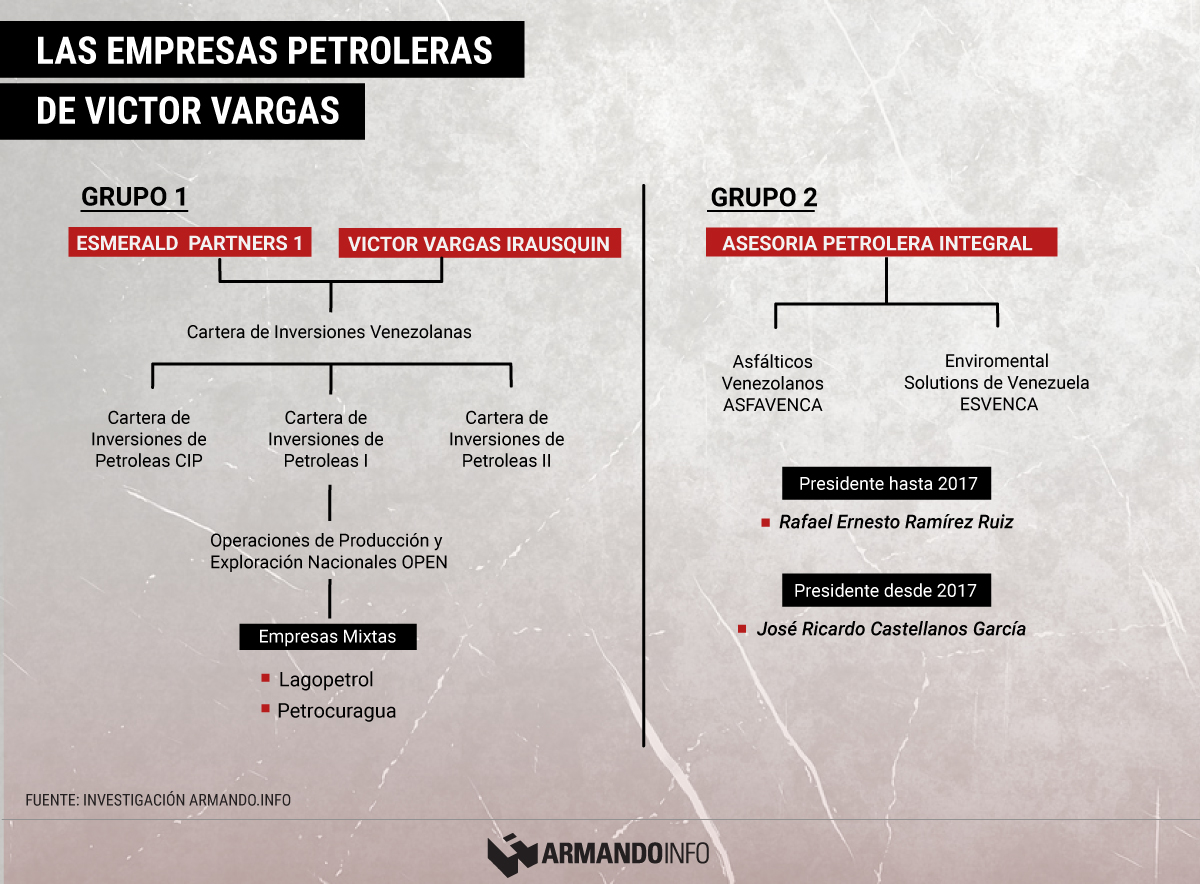

B.O.D. acted as the backbone for the financial group that spread across several Caribbean jurisdictions, including Curacao, since 1994. The bank became the sixth in the national ranking and Vargas bought the tower of the former Banco Consolidado, also in La Castellana and less than a block away from the former headquarters of Banco Barinas, to house the bank’s management. In 1991, he had incorporated Cartera de Inversiones Venezolanas C.A., the holding company for all his businesses in Venezuela, also owned by Esmerald Partners I, a Luxembourg registered holding company.

But at the height of this spectacular wave of expansion in the mid-1990s, Victor Vargas seemed to understand that being a true magnate in Venezuela ―both in times of oil wealth and impoverishment of these late Chavista era― means getting your hands on the oil business, the only one on a global scale that can be done from the country. The situation looked favorable. With crude oil prices at rock bottom, the then president of the state oil company PDVSA, Luis Giusti, was promoting a controversial plan to open up the market to the participation of private capital, national or foreign, through joint ventures or the granting of concessions.

Anyone who has taken an x-ray of Victor Vargas’ business group in Venezuela and abroad knows that it is made up of a web of hundreds of companies spread worldwide, including companies exclusively engaged in owning real estate, polo horses and airplanes. It was no different than in the oil sector, where he built a fractal reproduction of that pattern. In Venezuela alone, he set up several oil companies: Cartera de Inversiones Petroleras I and II, as investment channels, and Operaciones de Produccion y Exploracion Nacionales (Open) C.A., a supplier. With Chavism in power, Vargas obtained shares in joint ventures where the state-owned Corporacion Venezolana de Petroleo (CVP) held the majority.

In 2006, Lagopetrol formed a consortium with Colombian oil company Hocol - controlled back then by the French Maurel & Prom - and with Ehcopek Petroleo S.A., of the Moschella group of Zulia. In 2012, the shares of Maurel & Prom were acquired by Integra Oil & Gas, another France-based company, the body of shareholders of which is led by Jose Luis Manzano, the controversial former Minister of the Interior of Argentine for President Carlos Menem. Its purpose was to put an area of Lake Maracaibo into production.

In another, Petrocuragua, Open teamed up with CVP in 2007 to exploit the Casma field near Anaco, State of Monagas, in eastern Venezuela.

In parallel with this organization chart, Vargas set up another structure for its oil business in Venezuela. Oil engineer Rafael Ernesto Ramirez Ruiz, now 66 years old, served as the pillar and facade of the structure, acting as sole shareholder and chairman of the Board of Directors. In this scheme, Asesoria Petrolera Integral Nacional (Apin) C.A., a holding company registered in 2001, but with Ramirez Ruiz as the only shareholder since 2014,―until then, companies Inversiones Rufalca and Desarrollos Alse S.A. had a share―began to control Asfalticos Venezolanos C.A. (Asfavenca) and Enviromental Solutions de Venezuela C.A. (Esvenca).

This structure in Venezuela also corresponded to a set of legal entities in Panama, which included Esvenca Panama, Holding del Sur S.A., Denter Inc and Petroway 2014. Vargas’ family members, relatives and friends usually appear as directors or proxies of these companies, but never Vargas himself.

Though, Enviromental Solutions de Venezuela C.A. (Esvenca) is, beyond doubt, the most valuable and profitable piece of all these companies. Initially registered in Zulia in 1997, its headquarters were transferred to Monagas in 2003, and presents itself as a service company. Every now and then, the press has referred to it as a beneficiary of contracts worth hundreds of millions of dollars from Pdvsa, as a perpetrator of labor abuses or as a beachhead for a scheme to privatize the Orinoco Oil Belt.

For the purposes of this story, however, Esvenca’s relevance is different. Its name appears in the report on a “suspicious” transaction prepared by the Central Bank of Curacao and Sint Maarten for the closure of Banco del Orinoco, referred to in the first part of this release.

The other key to the story is in three documents filed with consecutive numbering in the First Notary Office in Caracas, on avenida Lecuna, a central avenue in the Venezuelan capital. All three are dated July 14, 2017, and refer to agreements between Esvenca, the Venezuelan company of Victor Vargas and Hanson Holland 2, a Dutch company, for the payment of a million dollar debt.

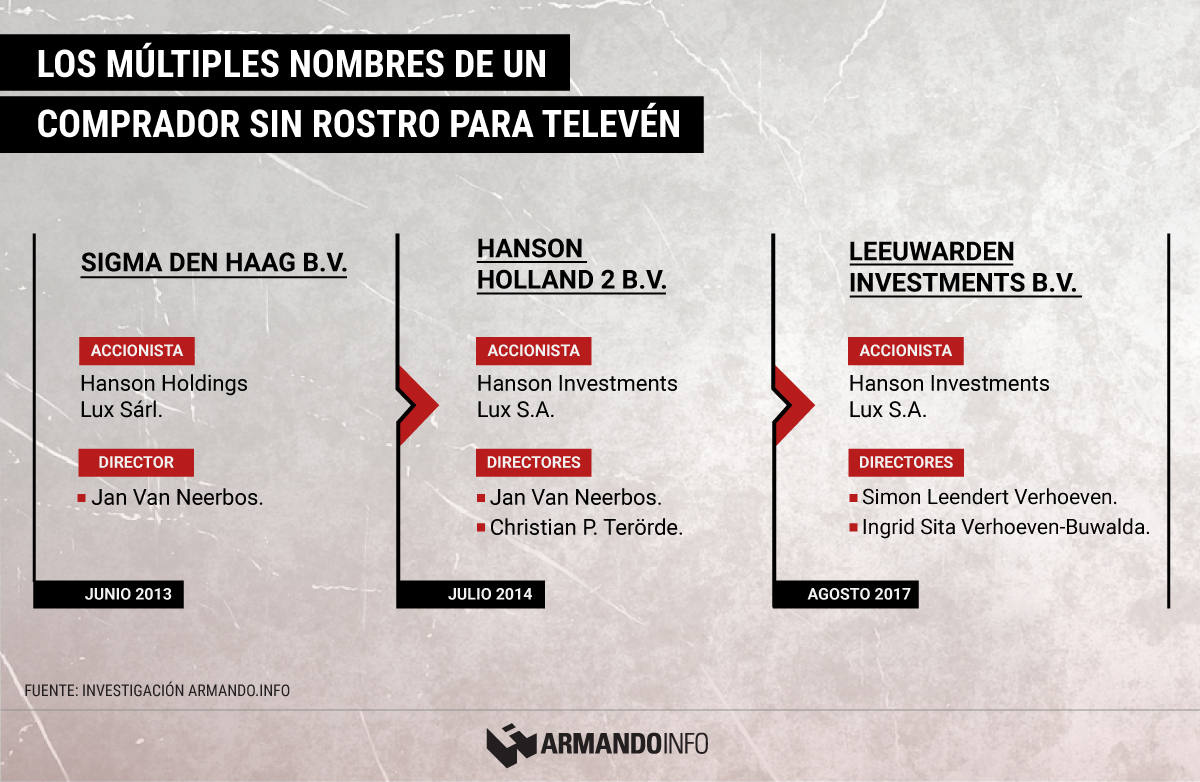

Hanson Holland 2 B.V. was the second name of a company incorporated in June 2013, under the name Sigma Den Haag B.V., in the Dutch city of Dordrecht, southwestern Netherlands. The name was change to Hanson Holland 2 B.V. in July 2014. In August 2017, it would be renamed Leeuwarden Investments B.V.

Just two months after the official act at the notary office in Caracas, Hanson Holland 2 was linked to the so-called Lezo Case in Spain, a judicial operation that uncovered corruption in Canal de Isabel II, the public water supply company of the Community of Madrid, when the politician of the Popular Party (PP), Ignacio Gonzalez, was president of the regional government. According to press reports, Gonzalez had received between 2014 and 2016, irregular payments of four million euros from Hanson Holland 2 through Renta 4 Banco in Madrid. The Hanson Group and Renta 4 were partners in a joint venture for asset administration and management, since February 2014.

But the truth was that by then, there was already a previous, more conspicuous and in the same way suspicious link between Hanson and Venezuela. It was the name that emerged from barely scratching the surface of Latam Media Holding, the Curacao-based company that in October 2013 appeared on paper as the buyer of Cadena Capriles, the country’s main news media group (now Grupo Ultimas Noticias).

The name Hanson refers to an investment group founded in 2010 by Englishman Robert William Hanson and German Christian Patrick Terörde. Robert Hanson, with the aristocratic title of Honorable, now 60 years old, brings reputation and lineage to the venture. The origins of the family business go back to the 19th century, with commercial and industrial developments that branched out during the 20th century into important companies, such as Imperial Tobacco and Milenium Chemical. Terörde is a professional born in 1974 in Düsseldorf, Germany, but a long-standing resident in London, where he has accumulated substantial experience in financial advising.

Under the Hanson Group’s imprint there are a myriad of legal entities, all controlled by one company, Hanson Holdings Lux Sárl, based in Luxembourg, Robert Hanson’s country of residence. One of these legal entities, Hanson Investments Lux, is the shareholder of Hanson Holland 2, today Leeuwarden Investments.

Consulting and asset management are the services offered by the Hanson Group, but in a brochure it is stated that “Discretion” is its product to safeguard “assets through secure and tax-efficient holding structures established for the long term and future generations” and “achieve the highest return possible based on each client’s acceptable risk level.”

That discretion was what Hanson brought in 2013 to the purchase operation of Cadena Capriles in Venezuela on behalf of an unidentified and certainly risky client ―in the banking jargon, probably a PEP (Politically Exposed Person), who was, as some publications have insisted since then, Tarek El Aissami Madah, former vice president of the Republic and former minister of the interior in the cabinet of Nicolas Maduro, and current minister of oil and responsible for the entire economic area. El Aissami, 45, and his alleged front man, Samark Lopez Bello, were subject to financial sanctions by the U.S. Department of the Treasury in 2017, and a trial for drug trafficking and conspiracy to launder money was opened against him in a New York court in 2019.

Both Hanson and Terörde, partners and founders of the financial group in Luxembourg, were part of the first board of directors of Cadena Capriles after it was acquired in October 2013 for nearly 120 million dollars. Carlos Jose Acosta, president of that board, had to admit that the nominal buyer, Latam Media Holding, “is owned by Hanson Group, established in England and with investments in different countries in Europe, Asia and America.” At least three representatives of Victor Vargas also appeared on the board, namely, lawyers Diego Lepage and Pedro Rendon, and Ricardo Castellanos Garcia, former marketing manager of El Nacional and Ultimas Noticias Caracas newspaper, who immediately gained the banker’s trust. The presence of his employees among the directors led some to think that Vargas had been the buyer of the publishing group, something that he denied with a statement in social media, “The purchase of Cadena Capriles by BOD Corp Banca and Victor Vargas is not true. It is not in our interest nor is it allowed by the Banking Law.”

Vargas had only acted as a financial facilitator for Hanson to acquire that media conglomerate on behalf of his client. The formula would be repeated two years later in another transaction, then truncated, to acquire Televen.

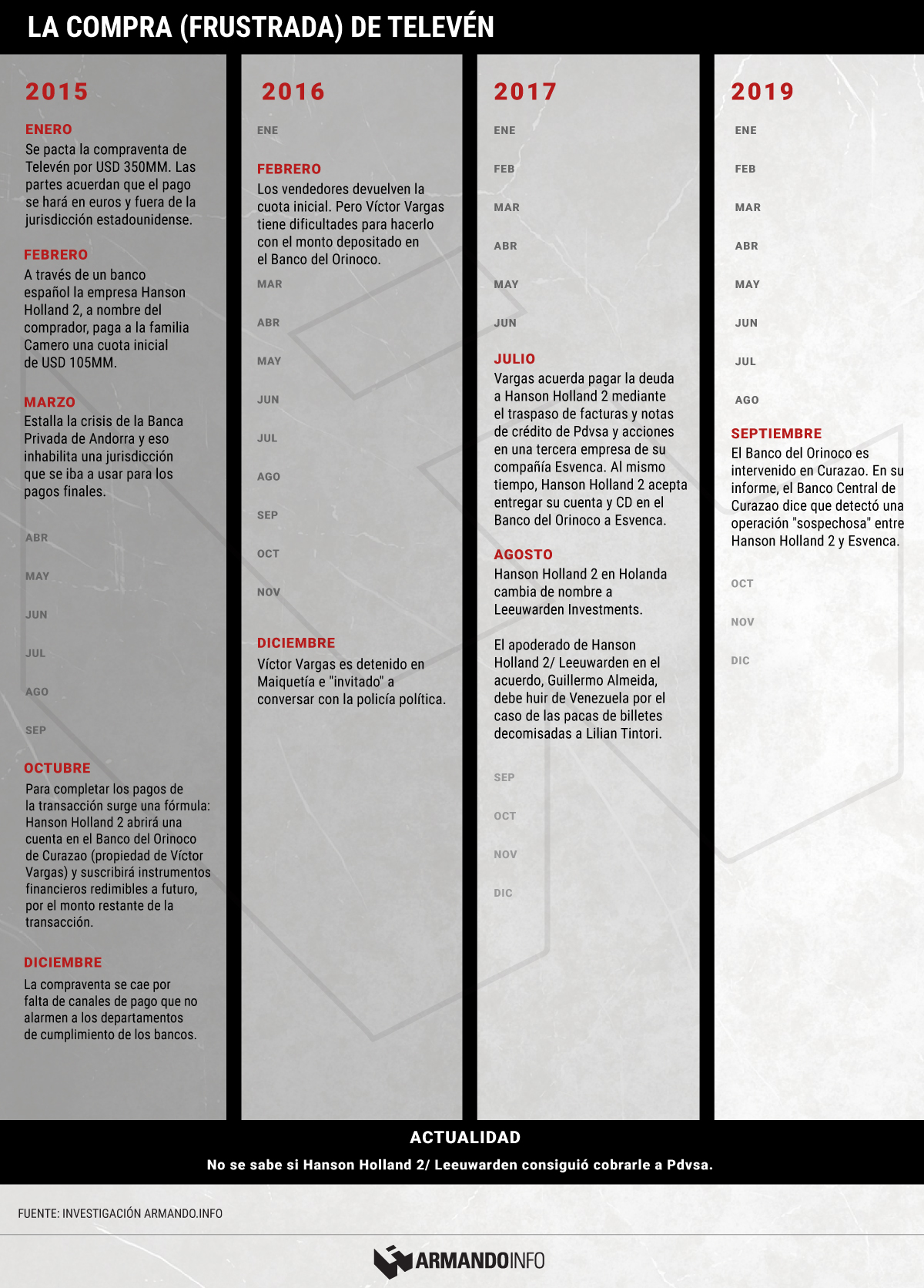

In 2015, some press reports echoed the attempt to buy Televen, a private television channel founded in 1986, which, after the disappearance of RCTV channel in 2007, easily established itself as the second most important and most watched channel in Venezuela, only behind Venevision, of the Cisneros Organization. Sources close to the negotiations now confirm to Armando.info that the Camero family, which owns the channel, had indeed agreed to sell it for the equivalent of $350 million, although the transaction would be made in euros for the sole purpose of avoiding the dollar sphere and thus, the oversight by U.S. anti-money laundering authorities.

On this occasion, the buyer would be Hanson Holland 2, instead of the Latam Media Holding that appeared in the purchase of Cadena Capriles. This choice had much to do with the Double Taxation Avoidance Treaty agreed upon in 1997 between Venezuela and the Kingdom of the Netherlands, a framework that would facilitate the operation. This company issued a General Power of Attorney to Christian Patrick Terörde in December 2014, five months after its incorporation. But the client in whose name the purchase was to be made was the same as that of Cadena Capriles… perhaps El Aissami again?

Hanson Holland 2 paid a down payment of 105 million dollars to the Camero family through transfers from a Spanish bank to a French bank.

But before the deadline for the final payments, scheduled by July 2015, something unusual happened. In the Principality of Andorra, a tiny tax haven nestled between France and Spain, the scandal of Banca Privada d'Andorra (BPA), one of the country’s main entities, broke out. As it was linked to money laundering operations in favor of top officials in Russia, China and Venezuela, the United States prohibited the bank from continuing to operate in dollars. That meant the end of the BPA business and the downfall of Andorra’s reputation as a safe haven for opaque financial flows. The ruin of BPA dragged its Spanish subsidiary, Banco Madrid, into intervention and closure. It was March 2015. The Andorran channel was thus blocked to complete the purchase of Televen, while leaving the American overseers with the radars in place. Omar Camero classified as PEP, certainly like the anonymous Venezuelan end-buyer. The banks that participated in the pledge down payment, with correspondent branches in the United States, refused to continue with the operation.

Ultimately, the problem of how to get the money to the seller, the Camero family, without generating compliance issues in the international banking system, turned out to be unsolvable and led to the collapse of the negotiation.

In late 2015, however, the legal-financial engineers of the operation believed they had found an alternative that included Victor Vargas and his besieged Banco del Orinoco, always thirsty for funds that would allow them to appear solvent. The formula required Hanson Holland 2 to open an account at the bank in Curacao and acquire fixed-term deposit certificates in which he would place the remaining amount for Cameron. Terörde made arrangements to open the account at Banco del Orinoco in October 2015.

When the Cameros finally stop the sale operation of Televen in December 2015, it was time to repay the prepaid money. They did their part, but then, another kind of problem appeared, Victor Vargas was not willing or able to return the cash that had been entrusted to him.

It is tempting to assume that these funds were sucked out of the hole that Victor Vargas was permanently trying to fill in the balance sheets of Banco del Orinoco by intensely pedaling his financial bike. However, this assumption could not be confirmed at the closing of this report.

Vargas’ difficulties to pay back led to measures to exert pressure, according to sources who spoke to Armando.info, provided their identity was protected. For a time, his private aircraft were banned from taking off from Venezuela, and payments to his oil companies were blocked in PDVSA’s administrative system. These sources also recall that, in early December 2016, Vargas was arrested at Maiquetia International Airport on his return from a trip abroad and taken for a “talk” at the Caracas headquarters of the Bolivarian Intelligence Service (Sebin, the political police of Chavismo). Vargas himself was quick to explain that the “invitation” to the police headquarters had been due to a blackout that had occurred days earlier in the interconnected electronic banking system of Credicard, ―a consortium in which B.O.D. participates together with other entities― which Nicolas Maduro’s government perceived as an attempt to sabotage public order.

In the meantime, a settlement was reached in 2017. The way Vargas found to pay is reflected in the documents, three, kept in the notary office in Caracas. Fortunato Lopez, an 82-year-old bank executive who has accompanied Vargas since the days of Banco Barinas, signed on behalf of Esvenca; and Guillermo Almeida Maya, another of Vargas’ trusted men, a lawyer, former manager of B.O.D.’s in-house law firm, Consultoría Empresarial Corporativa (Cecca), and director and attorney-in-fact of some companies of the Venezuelan banker’s corporate assortment, signed on behalf of Hanson Holland.

Under the settlements, Esvenca agrees to transfer to Hanson Holland 2, in the form of a payment, a little over 800 invoices already accepted by PDVSA for a value of a little less than 31 million dollars. It also assigns to Hanson Holland 2 a couple of credit notes issued by PDVSA in June 2016, in its name, payable quarterly until June 2019, at a 6.5-percent annual interest rate for a face value of just over 66 million dollars. However, Hanson Holland 2 B.V. accepted them at a 60-percent discount, i.e. for $26 million only.

Fortunato Lopez, on behalf of Esvenca, informed the transfer to PDVSA, at a time when Simon Zerpa - now supposedly being pursued - was the Vice President of Finance of the state oil company, a position he held until February 2018. Zerpa has also been subjected to sanctions by the United States.

“The payment was deposited in the Noor Capital Bank in Dubai. This entity has participated in the business schemes of Tarek El Aissami and Alex Saab.”

In addition, Esvenca included in the payment the restitution of shares worth $22 million in TAM Total Recovery Fund Ltd, a company incorporated in the Cayman Islands, another Caribbean tax haven, together with Hanson. TAM stands for Trebol Asset Management, a Swiss company specializing in wealth management, where Simon Leendert Leo Verhoeven works, one of the registered directors of Leeuwarden Investments, now known as Hanson Holland 2.

Incidentally, when Fortunato Lopez subscribed the shares of TAM Total Recovery Fund, again on behalf of Esvenca, he deposited the payment in the Noor Capital Bank in Dubai. This entity has often been referred to as an extension of the business schemes of Tarek El Aissami and Alex Saab, the commercial factor and alleged front man for Nicolas Maduro, recently arrested in Cape Verde. It is also known that a TAM subsidiary, Trebol Investment Luxembourg, as well as Noor Capital Bank itself, were the channels used to transfer the foreign currency payments with which Cilia Flores’ children bought some of the houses on avenida Laguna de Tacarigua, in the Cumbres de Curumo area, southeastern Caracas, which they eventually closed for them alone.

Armando.Info tried to contact Victor Vargas, Guillermo Almeida and Simon Leendert Verhoeven by email to obtain their versions. However, there were no responses.

The sum of the different assets whereby Victor Vargas’ oil company, Esvenca, offers to pay the debt to Hanson Holland 2, under the settlement, amounts nearly to 79 million dollars. It is not known if it corresponds to the total amount owed by the Barinas-born banker.

Under the same notarized settlements, Hanson Holland 2 disposed of all its assets deposited in Banco del Orinoco in Curacao and transferred them to Esvenca, including a bank account and at least ten financial instruments. This is the operation that the Central Bank of Curacao and Sint Maarten would challenge for being “suspicious” when taking over the entity in September 2019.

By the time of the deal, Victor Vargas had already ordered the dismissal of engineer Rafael Ramirez Ruiz from the boards of directors of those companies, both in Venezuela and abroad, which he had incorporated ad hoc to address the oil business. In each of them, including Esvenca, Ramirez was replaced by Ricardo Castellanos Garcia in April 2017, three months before the payment settlement reached with Hanson Holland 2 B.V.

The settlement would suffer some minor disruptions that should not have hindered compliance thereof.

First, the partners in Europe decided to change the name of Hanson Holland 2 B.V. to Leeuwarden Investments B.V.

Soon after, something bigger happened. On August 29, 2017, Sebin commissions detected bales of bills worth 205 million bolivars in an SUV of Lilian Tintori, the wife of then-imprisoned opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez, who is currently taking refuge in the residence of the Spanish ambassador in Caracas. Subsequent investigations determined that this amount had been part of a remittance of 800 million bolivars in cash that B.O.D. officials had given to Guillermo Almeida Maya, attorney for Victor Vargas and proxy for Hanson Holland 2. Almeida was then forced to flee the country and settle in neighboring Colombia.

Thus, Victor Vargas, the banker and a “socialist in the true sense of the word” could settle a debt that seriously threatened to prevent him from continuing to enjoy his polo matches, his voyages on the Norman Foster-designed 200-foot yacht, and his family retreats in the Andalusian reserve of Sotomayor.

At least until Curacao learned of a hole in Vargas’ Banco del Orinoco that he could no longer fill.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.