Without human rights officers at the ports of entry or legal system that protects the refugee, Venezuelans migrating to the Caribbean island find relief from hunger and shortages. In return, they are exposed to labor exploitation and the constant persecution of corrupt authorities. On many occasions they end up in detention centers with inhumane conditions, from which only those who pay large amounts of money in fines are saved. The asylum request is a weak shield that hardly helps in case of arrest. Yet, the number of those who try their luck to earn a few dollars grows.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Andrea counts the days to return, not many now. In Tucupita, the capital of the Venezuelan state of Delta Amacuro, her two children await her, and she will arrive, or so she expects, with 700 American dollars that she saved working two and a half months in Cedros, a coastal town on the southwest tip on the island of Trinidad.

She helped in a courier company and cleaned houses. She left the school where she taught in Venezuela and displayed her knowledge as a Bachelor of Education with a Master’s degree in Educational Psychology behind. She was not making ends meet. When she returns to mainland, she hopes to live off what she buys with the sale of the dollars, little by little, for at least six months, to return to Trinidad and repeat the operation. She hopes to support her family in hyperinflationary Venezuela under this architecture of seasonal travels.

At first sight, Cedros, on the Trinidadian coast, is like any Venezuelan beach, Higuerote, Cuyagua or Punta Arenas, but without reggaeton in the background or "empanadas". The sand is fine and brown, the water is warm.

most come to Trinidad with a single goal: to work and earn in dollars to help those who stay at home.

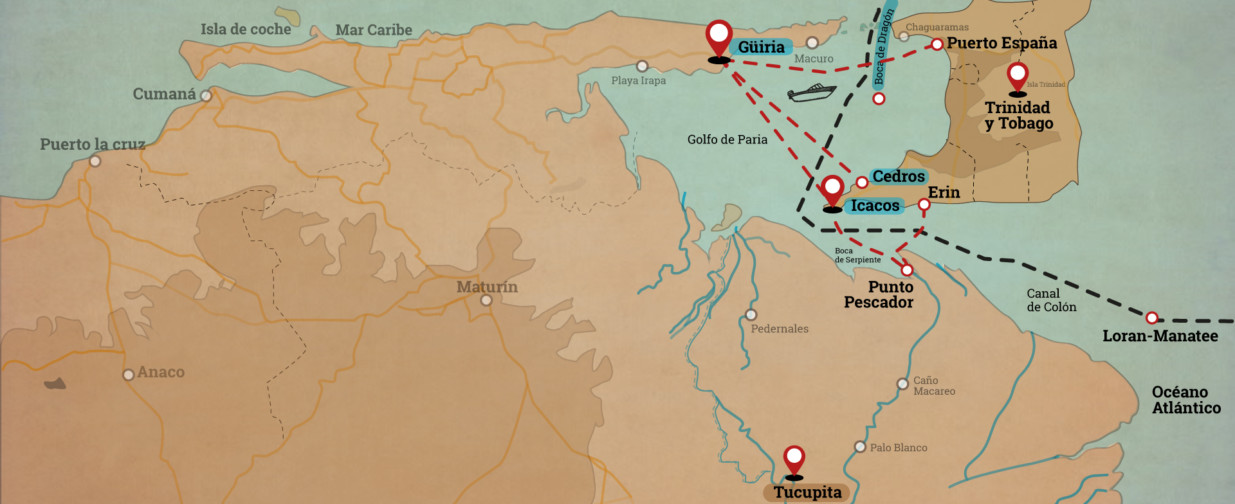

On a long concrete jetty that serves as a pier, the line of those who have their papers to enter legally is formed. Around four boats arrive every Thursday, each with at least 20 Venezuelans seeking to escape from hunger and shortages, which represent their homeland these days. Family or friends wait for them under a tree to prove, if necessary, that they are invited by someone.

Yes, the landscape reminds us of Venezuela but everything suddenly changes. A Trinidadian official shouts the names of the newcomers with a strong English accent. If anyone is waiting for Venezuelans when called, they are sent back.

Once you set foot in Trinidad, the real odyssey begins. Arriving Venezuelans usually make one of these two decisions: the one made by Andrea, entering legally, staying a while and returning, or remain indefinitely seeking international protection as a refugee.

Those who do not have passports disembark on the beaches of Icacos -even farther west than Cedros- or Erin -more to the south-, where there are no official entry points and the welcome is offered by the gentle beach, the night and the silence. The fishermen of the area acknowledge that many Venezuelans enter "but less and less from here," according to Selwyn Joseph, who lives in Icacos, "There are more surveillance patrols lately." Regardless of the strategy, most come to Trinidad with a single goal: to work and earn in dollars to help those who stay at home.

Unlike other countries bordering Venezuela, which for months have had some legal and logistical apparatus to receive the growing flow of those escaping the crisis, Trinidad and Tobago hardly improvises. According to the Chief of the Immigration Office, Charmaine Gandhi-Andrews, in 2015 only six Venezuelans had requested asylum, but the number rocketed to 2,000 applicants in 2017, mostly processed by the Catholic refugee service agency Living Water Community (LWC), a sort of an executive branch of the United Nations Agency for Refugees (UNHCR).

Although they do not offer information on the number of applicants, the LWC spokespersons slip a calculation: each week they receive 150 to 180 Venezuelans requesting asylum, and their projection for year end is that at least 10,100 will be in the island asking for protection. According to the Trinidadian authorities, in 2017 alone, 27,000 Venezuelans entered through the official ports of entry.

However, being on the LWC list does not represent a solution for Venezuelans seeking protection and refuge in Trinidad and Tobago. The legal scaffolding of the Caribbean country to deal with migration is limited to the Immigration Act of 1969, amended for the last time in 1995, and where there is not a single reference to the figure of asylum or refuge. The misalignment of this law with the present time dates back to the use of an archaic and discriminatory language, like the express prohibition to enter the country for "people who are persons who are idiots, imbeciles, feeble-minded and insane persons, and who are likely to be a charge on public funds” (article 8(a)),"persons who are dumb, blind or otherwise physically defective, or physically handicapped, which might endanger their ability to earn a livelihood" (article 8(c)), or "prostitutes, homosexuals or persons living on the earnings of prostitutes or homosexuals" (article 8(e)).

A strong flow of Cuban migrants who arrived in Trinidad in 2014 finally led to the creation of an Immigration Unit. In 2016, Acnur opened an office in Port of Spain, the capital of this Caribbean nation that comprises of two islands. But these instances were soon surprised by the arrival of Venezuelans en masse. "There had never been a migration of Venezuelans like that," explains Rochelle Nakhid, director of LWC. "We are receiving more and more people without passports. They always show the identity card. Some arrive by plane, but most of those who enter by sea do not have documentation, and almost all say that they are looking for a better life, ways to send food to their homes or medicines."

Without regulations or laws that support the status of asylum or refugee, Trinidad and Tobago does not grant this status to anyone, despite being a signatory to the Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, created in 1951 by the United Nations. LWC just provides a paper warning that the bearer is an asylum seeker and the Immigration Office of Trinidad and Tobago provides a similar document, although printed on yellow paper and with a couple of conditions: Venezuelans must submit their passport to the Immigration Office and appear before that instance on a regular basis.

This last document is known as "order of supervision" and they usually give it also to migrants who were arrested because they entered the country illegally and had not requested asylum. The detainees in these conditions, who want to request protection once arrested, can only obtain the "yellow paper" if they pay a fine or serve their time in prison.

In practice, none of these papers is equal to obtaining refugee status. Nor do they imply a formal residence and, worse still, they do not mean a permit to work or study, in the case of minors. "The paper from LWC or the yellow paper generally is an alternative to being arrested. It provides them with protection from being deported or under arrest. It is the only mechanism available," Nakhid points out.

But to Jean Carlos Anaya, for example, the paper provided by LWC did not help him. He has an associate degree in IT, born in Valencia, capital of the state of Carabobo (center of Venezuela), is a prisoner in the IDC, Immigration Detention Center, built in 2009 in Aripo, almost an hour from Port of Spain. He arrived in Erin without a passport when the boat trip from Tucupita, in last year’s November, could still be paid in bolivars. Soon he settled in a room and started working in a chicken farm, then in a hardware store, in both cases, as an illegal and earning up to 1,500 Trinidadian dollars a week (214 US dollars), which he distributed so that he managed to send money to his fourteen and six-year old children.

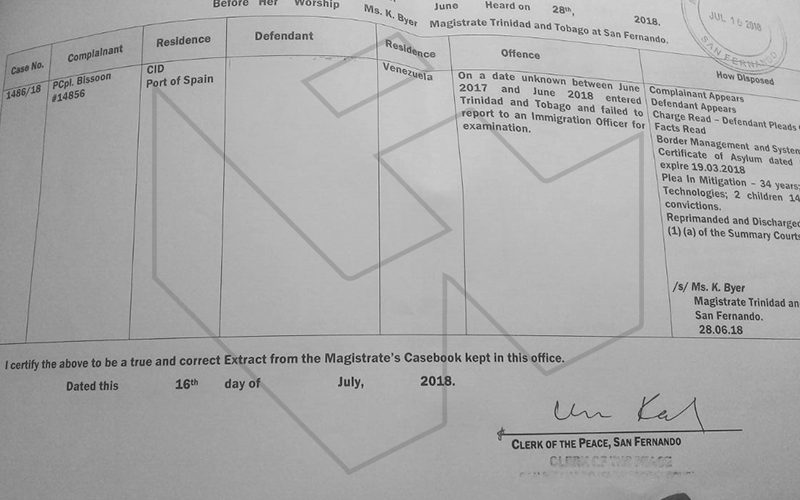

"I was good with money. The first week I paid for the room, the second and third week I bought food, and I sent to Venezuela what I earned in the fourth week," he says in a telephone call from the IDC. "I worked from sunrise to sunset. I could settle and was happy. Two months later, I went to LWC and obtained my paper as an asylum seeker, like my brother, who arrived with me and is also in prison here." Both were arrested after a party in the coastal area of ??Los Iros, despite of showing their asylum seeker certificates — "I didn’t know that there was so much patrolling," he complains. The police overrode. "They asked for a $ 1,000 each to let us go. I only had TT$ 700 cash, so they arrested us."

That happened in June 2017. Anaya was imprisoned in the IDC before he was presented in court. After verifying that he was an asylum seeker registered with LWC, the court decided to give him a verbal reprimand only and ordered his release "in the next few days". But the native of Valencia was transferred to the maximum security prison (MSP) with common criminals. He stayed there for seven days without receiving any explanation and then back to the IDC, where he remains imprisoned to date. His brother, who entered Trinidad like him and was arrested in the same circumstances, has not even been brought before a court.

"I know my rights. The court ordered my release, but I am still here. I asked for international protection and I have a paper that guarantees it. I'm just waiting to get out of here and I'm going to sue Trinidad and Tobago," says Jean Carlo, who despite being holed up, does not want to return to Venezuela. "With much grief I must say that I cannot go back. I need to keep working, earn money and send it to my home. You need to understand my desperation. My children and my mother depend on me."

Most of the arrested immigrants must pay a penalty of up to three years in prison or a fine of up to 2,100 Trinidadian dollars (about US $ 300), equivalent to a potential return ticket to their country of origin. Between loneliness and poverty, not everyone has friends or resources to cover that expense. In addition, the amounts of the fines are sometimes set discretionally, as well as the bails.

José Heredia, has spent exactly six months trying to collect the 3,000 US dollars (21,000 Trinidadian or titi dollars) required to get his friend Ericson out of prison, arrested in December 2017 and sentenced in less than a week to three years in jail for entering Trinidad illegally. "It was all very fast, without a lawyer, nothing," says Heredia, "They told us that if he doesn’t pay the fine he will have to pay the penalty in the maximum security prison, but the amount is high and it has been difficult for me to collect it."

Not long ago, the transit of Venezuelans was a routine matter in Trinidad and Tobago because it was just that, transit. In Cedros and Icacos, almost everyone remembers that arrival routine of Venezuelans on Fridays to party or go to the beach on the weekend, buy something and return on Sunday. Another of the classic activities of Venezuelans, especially middle class, was to go for a few months to study English. On the other hand, many Trinidadians remember that they liked to travel to Margarita Island and Cumana, and those with more resources, to Puerto La Cruz - all tourist enclaves of the Venezuelan northeast - or to Caracas, where they could enjoy the frenzy of a big city that used to emanate from the Venezuelan capital.

The change began in 2015 with the collapse of both oil-dependent economies -a catastrophic fall in Venezuela’s case- and the growing number of Venezuelans arriving and remaining in a country whose native population was going through the lean times. The smile that was reserved for the tourist transmuted into distrust for the immigrant, a little fairer in skin than the Trinidadian, with little understanding of English and definitely with less available resources than the Venezuelans in the past. The constant police patrol on the street, especially in Port of Spain, the legal limbo of their situation and the scrutinizing looks of the locals keep Venezuelans hidden in their homes or jobs. "Hello Spanish," as a greeting on the street, is not exactly welcoming.

Norka Delgado and her two children do not speak Spanish when they go to the city center, and they hardly go out. "We whisper. We do not want to attract attention. Here we are Spanish, Latin." The Trinidadian Government is so rigid with immigrants that even if an alien has a resident status, their children are not admitted to the formal education system unless they have the same status. Norka, a Venezuelan resident—because her father is Trinidadian—, an administrator by profession and a waitress by necessity, has over a year in Port of Spain, but her 14 and 16-year old children are not admitted to any school.

"That greeting implies that you are an alien, different," explains Arnaldo Gómez, a Venezuelan journalist caught in the legal limbo of being an asylum seeker without the right to study or work, "it is a phenotype observation." Gómez arrived in 2016, and claims to be one of the first Venezuelans to apply for asylum in Trinidad. He started organizing boxes in a shop, of which he is a sort of a manager today, because he earned the trust of the owners. Considering the time elapsed, he can affirm that the treatment of the Trinidadians has deteriorated rapidly. In a recent release, the Newsday newspaper of Port of Spain dared to describe the Venezuelan migration as an "invasion."

"From the moment I asked for asylum, they told me that I could not stay, but they offered to send me to another country in a resettlement process. We chose Canada. I had a very cordial interview at the immigration office. I appeared at the office every three months. Then, in the second interview, they took my passport and asked me to appear every month. In last year’s July, they should have helped me with the resettlement or at least give us the residence or work permit, but nothing happened. They told me that there will be no resettlement. It is a legal nonsense. They push people towards illegality and they know it. We do not exist in Trinidad," he explains.

In this context, Venezuelans do not adapt, they feel in an eternal transition. Most expect to be able to save and go elsewhere, but many, like Gómez, face another problem, the expiration of their passports and the impossibility of obtaining a new one through the website of the Venezuelan Immigration and Naturalization Service (Saime), because when filling out the electronic form, there are the tourist and resident categories only, there is no refugee category. Venezuelan immigrants in Trinidad are neither tourists nor residents.

With no work permits, arriving Venezuelans can only relocate in jobs as taxi drivers, construction workers, masons, waiters, household employees. Trinidadians express fear that this flow of immigrants will fill the jobs; hence, many applaud the official tightening policy towards immigrants declared by the prime minister in late July. However, not everyone panics. "People think that Venezuelans will take our jobs. They get scared because the economy is bad," says a Trinidadian taxi driver with a strong Hindu accent during a long trip, "but the truth is that there is a lot to do here and a little help would not hurt."

The condition of illegality to work - with asylum seeker paper or not - usually means that the payments received by Venezuelan immigrants are well below the minimum wage. On the coast, where the most common trades are related to work in the country, on farms, in fishing or in informal commerce, is even worse. But Venezuelans accept it. Any dollar multiplies exponentially when sent home. "Trinidadians work for 350 titis a day (US$ 50), but we are paid 150 titis, depending on the work," says Magda Estaba, a 45-year-old Venezuelan who lives in Icacos, but who has also become a kind of guide or leader for the growing community of newcomer compatriots.

"I help as I can. Sometimes I lend money for them to show that they can be on the island and then they pay me back, but mostly, I try to help them find work. In the coconut processing plant at the beach alone there are five Venezuelans, and I got them the job," she says proudly, although not trying to idealize that work. She knows, for example, that the work in the country could entail a twelve-hour day. "Those who want to stay obtain their paper as asylum seekers in Port of Spain and stay in those jobs, but many, especially those who come with the family, end up returning because the children cannot attend school."

In Port of Spain, wages improve a little. But the costs of living in the city are also higher. You can find at least one Venezuelan waiting tables in almost every restaurant in the capital of Trinidad, which by some prodigy seem to be exempt from police raids. However, a great vulnerability is perceived even among these privileged immigrants, who enjoy regular employment and salary.

Women take care of each other with dedication, because, since they look different, they are in great demand in the business of sex slavery. Malena Rodríguez is a girl from the island of Margarita who has been an immigrant for nearly two years. She entered the island of Tobago, more rugged and northern than Trinidad, but today, she lives on the main island. She has the marks and scratches from what she describes as an attempt to kidnap her in April of this year, when she took a taxi on the street. "I was going from home to work, a route that I do all the time, but the taxi got diverted and turn off and drove through an unknown area. I asked the taxi driver where were we going and he did not answer me. The second time, he accelerated and I jumped off the car while still in motion. Luckily, I could stand up and run. Who knows what he was going to do to me," she recalls.

Now, she only uses an Uber-like taxi service, which is the same used by all of her co-workers, waitresses at the bar on Ariapita Avenue in Port of Spain. She hopes to save enough to leave soon. "Trinidadians does not treat aliens well," she says. Nearby, at least five Venezuelans work in prostitution guarded by burly Trinidadians. They look very young and their accent stands out, like that of two Cuban girls. None of them wants to tell how they got there.

* The identities of all Venezuelans quoted in this report have been changed to protect their immigration status and procedures before the government of Trinidad and Tobago.

They lose their freedom as soon as they set foot on any Trinidadian beach, and their “original sin” is an alleged debt that these women can only pay by becoming sexual merchandise. They are tamed through a prior process of torture, rotation and terror, until they lose the urge to escape. The growth of these human trafficking networks is so evident that regional and parliamentary reports admit that the complicity of the island’s justice system in this machinery of deceit and violence multiplies the number of victims.

Two entrepreneurs from Peru, Yosef Maiman and Sabih Saylan, participated as intermediaries in the irregular payments of Odebrecht, through offshore structures, to the former president of that country. They are part of a "shell companies" structure built by Mossack Fonseca, as shareholders of the private cable TV and telephone operator in Venezuela, Inter. Even the Panamanian law firm suspected that it was being used for money laundry. Meanwhile, another firm of the group contracted works with the Chavista State.

Since the borders to Colombia and Brazil are packed and there is minimal access to foreign currency to reach other desirable destinations, crossing to Trinidad and Tobago is one of the most accessible routes for those in distress seeking to flee Venezuela. Relocating them is the business of the 'coyotes' who are based in the states of Sucre or Delta Amacuro, while cheating them is that of the boatmen, fishermen, smugglers and security forces that haunt them.

The network of intermediaries contracting with the Venezuelan Foreign Trade Corporation (Corpovex) to bring CLAP boxes seems infinite. In Sabadell, a town near Barcelona, a virtually cash shell company got 70 million dollars for outsourcing the shipment of food to Venezuela thanks to the administration of Nicolás Maduro, which buys the contents of the boxes at discretionary prices and without control. Last year alone, the government spent 2,500 to 3,500 million dollars, but only the leaders of the "Bolivarian revolution" know the actual figure.

The chemical analysis of eight Mexican brands that the Venezuelan government supplies to the low-income population through the Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP), gives scientific determination to what appeared to be an urban legend: it may be powdered, but it is not milk. The fraud affects both the coffers and the public health, by offering as food a mixture poor in calcium and proteins, yet full of carbohydrates and sodium.

Even Diosdado Cabello has false followers. The Government of Venezuela has been able to measure itself in political cyberspace. Hence, it has created an authentic machinery of robots at the service of the governing party in social media that is mainly controlled by public officials and coordinated from ministries. This is the result of several studies, testimonials and applications that measure the "Twitterzuela" convulsion.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.