Even Diosdado Cabello has false followers. The Government of Venezuela has been able to measure itself in political cyberspace. Hence, it has created an authentic machinery of robots at the service of the governing party in social media that is mainly controlled by public officials and coordinated from ministries. This is the result of several studies, testimonials and applications that measure the "Twitterzuela" convulsion.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

At the cry of "troop", Mario Silva, a legendary presenter of the Venezuelan television channel (VTV), used to decree trends on Twitter. The call to post tags favorable to the ruling party in this social media was followed by other faces of the public television. Thus, Chavismo has earned for years a privileged space on the Trending Topics list in Venezuela. But that is not the result of force of popularity or simple influence of followers only. Or, at least, that is what documents like last year’s leak from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Justice and the virtual programs that detect a virtual army at the service of the self-styled Bolivarian revolution showed.

The Government of Venezuela stands out among 28 countries evaluated by the University of Oxford, presented in the report "Troops, Trolls and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation" (published in 2017), which appeal to a range of cybernetic tools to try to penetrate virtual audiences. Based on the 37-folio study, these troops are directed from the Ministry of Communication and Information with money from the Venezuelan State and with political objectives. Other nations analyzed were Vietnam, North Korea, Ecuador, China, the Philippines, Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Israel, Mexico, the United States of America, Ukraine, Germany or India. "Cybernetic troops are often made up of a variety of different players. In some cases, governments have their own internal teams that are employed as public officials. In others, talent is subcontracted to contractors or private volunteers," explains the study.

At the cry of "troop", Mario Silva, a legendary presenter of the Venezuelan television channel (VTV), used to decree trends on Twitter. The call to post tags favorable to the ruling party in this social media was followed by other faces of the public television. Thus, Chavismo has earned for years a privileged space on the Trending Topics list in Venezuela. But that is not the result of force of popularity or simple influence of followers only. Or, at least, that is what documents like last year’s leak from the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Justice and the virtual programs that detect a virtual army at the service of the self-styled Bolivarian revolution showed.

The Government of Venezuela stands out among 28 countries evaluated by the University of Oxford, presented in the report "Troops, Trolls and Troublemakers: A Global Inventory of Organized Social Media Manipulation" (published in 2017), which appeal to a range of cybernetic tools to try to penetrate virtual audiences. Based on the 37-folio study, these troops are directed from the Ministry of Communication and Information with money from the Venezuelan State and with political objectives. Other nations analyzed were Vietnam, North Korea, Ecuador, China, the Philippines, Iran, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Israel, Mexico, the United States of America, Ukraine, Germany or India. "Cybernetic troops are often made up of a variety of different players. In some cases, governments have their own internal teams that are employed as public officials. In others, talent is subcontracted to contractors or private volunteers," explains the study.

Two testimonies found by Armando.Info agree that the orders are issued from an office of the Ministry of Communications and Information, exclusively enabled to coordinate social media, and sometimes they hire the services of private companies engaged in the virtual world. The manual of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, Justice and Peace, entitled "Training Project of the Bolivarian Revolution Trolls Army to face the Media War" - leaked to the Institute of Press and Society of Venezuela in 2017 -, gives instructions for the consolidation of a virtual battalion. Throughout 14 pages, the manual warns that the cybernetic army will be made up of several squads: press, design, IT, content "incubators," and an attack squad called "flames," which is capable of sowing "false positives."

This entire organization chart operates from three command posts divided in the creative, IT and those commissioned to attack. Thus, in the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Justice only are over 600 people - among employees and contracted - in charge of around 15,203 accounts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, Google+ and Whatsapp. Of the five squads projected in that portfolio, the one of the "fake news" or "false positives" stands out. "In times of tension or conflict, the order was to generate rumors or false news to confuse and thus, subsequently, disprove and discredit certain characters of the opposition," says an insider who was part of the troop.

Undoubtedly, the Government has tried to use social media as a measure of popularity. President Nicolás Maduro has assumed the challenge imposed by cyberspace as a real war. In June, the Head of State criticized the Twitter company for deactivating thousands of accounts of activists of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) "just for being Chavista," while arguing that it was "fear" because the governing party entails a political "majority" in this country. "Of course they (Twitter) have the key, they have the server and they said 'it's over', and they closed thousands of our accounts, but if they closed a thousand accounts, we will open 10,000 more with the youth and the revolutionary force of public opinion and the Venezuelan truth... The battle in social media is very important. They know that it is very important and they use social media for permanent psychological warfare," he said. The claim was made while anti-government protests were taking place between April and July, one of the most discredited episodes for Chavismo due to the death of over 120 people and hundreds of arrests.

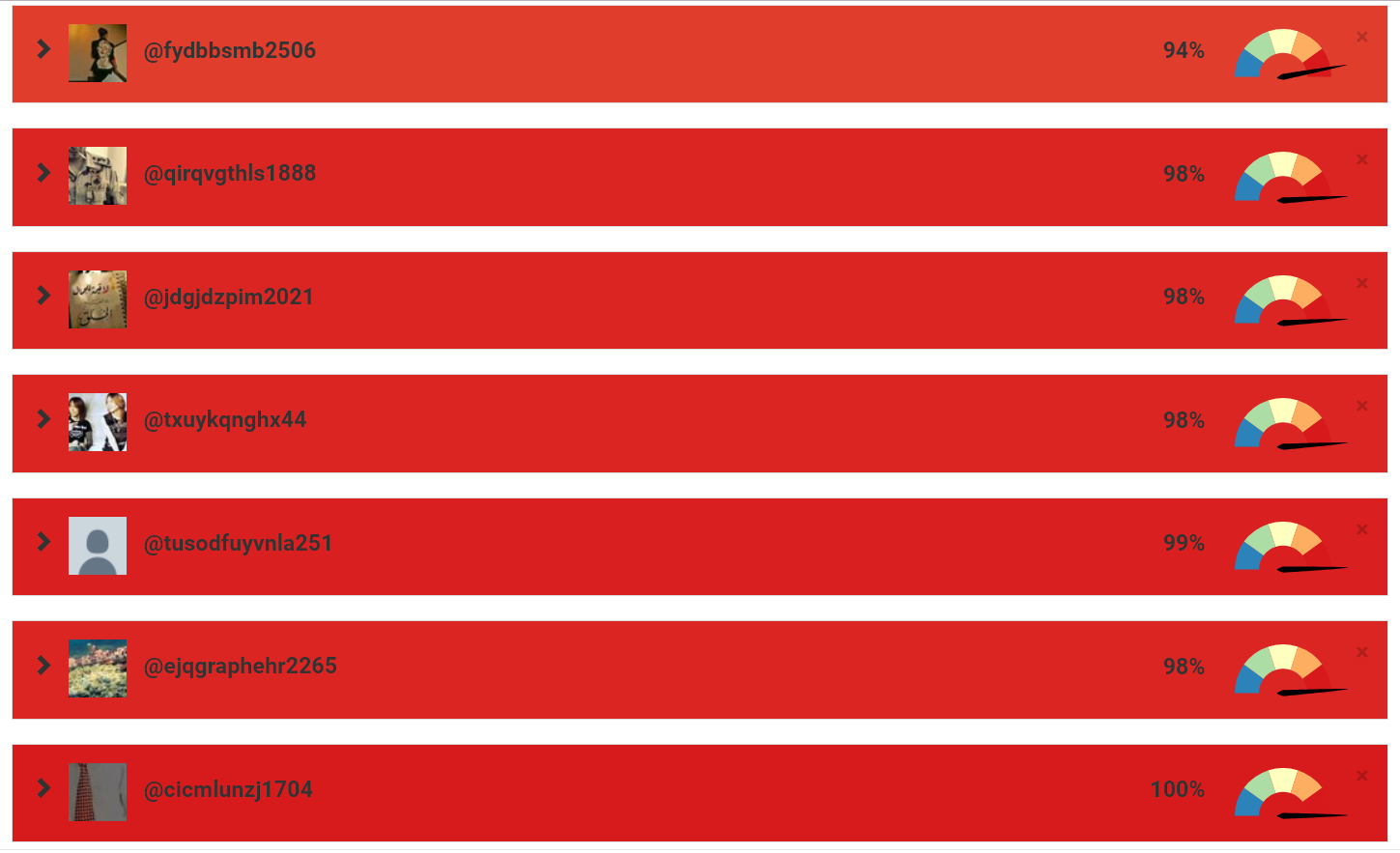

Thanks to the Botometer application, Armando.info analyzed several Twitter accounts of politicians related to the ruling party. The one of Diosdado Cabello -one of the hierarchs of Chavism- portrays him with false followers. Of a sample of a thousand of its two million followers, 15% are part of inactive users, robots or spammers.

The figure, however, is not entirely atypical either, as 9% to 15% of active Twitter accounts behave like bots, aimed to act with different "target" groups to influence opinions and thus publish content of connected applications, according to the conclusions of the Eleventh International Conference of the AAAI (Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence) on Web and Social Networks, held in 2017.

But it can be about the smallest calculations against the sophisticated mechanisms to create false profiles in social media. Luis Carlos Díaz, a journalist focused on the study of social networks, indicates that in the detection of a false Twitter account, the outdated metrics are no longer valid. "The question of whether or not it has an identity has already been overcome. When one follows the false accounts of the Government they have a face, an avatar, a name. How are they detected? The idea is to see the trends that the Government originates in Twitter; for example, verify some key details: a same tweet, replicated again and again, can offer us indications of inorganic accounts."

"Undoubtedly Maduro has fake accounts and an army of bots to replicate content and echo in favor of official propaganda.

Many of Chavismo's accounts have a profile characterized by spreading rumors and conspiracy theories, in the Marxism-Leninism propaganda style. It is not an exclusive issue of Venezuela. In the Philippines, many of the so-called "keyboard trolls" were hired to spread propaganda for presidential candidate and current head of state Rodrigo Roa Duterte during the election. Based on the Oxford study, this strategy has been continued with the aim of spreading and amplifying messages to support his policies now that he is in power.

Twitter has a specific role in Venezuela because it has become an information channel against the censorship of traditional media. Díaz explains, however, that in that virtual ecosystem there is a voracious contest between political players. “Undoubtedly Maduro has fake accounts and an army of bots to replicate content and echo in favor of official propaganda. That is a reality."

In the history of the virtual battles of Chavismo, Díaz adds an unforgettable anecdote, the use of an application to attract followers during the presidential campaign of Nicolás Maduro, in 2013. "Many people joined the official website of the then candidate of the governing party. After registering their Twitter accounts, they automatically retweeted content favorable to Maduro. The trap was evident after the company suspended thousands of users for that reason, as it has done on other occasions. In addition, there are many complaints from laboratories operating in the state Aragua, especially during the government of Tareck El Aissami, and with the support of state officials and public institutions for the purpose of conducting official campaigns through social media.”

The political turmoil of the Bolivarian Republic is not alien to the Web. With bots and robots, Chavismo creates its virtual reality.

Two entrepreneurs from Peru, Yosef Maiman and Sabih Saylan, participated as intermediaries in the irregular payments of Odebrecht, through offshore structures, to the former president of that country. They are part of a "shell companies" structure built by Mossack Fonseca, as shareholders of the private cable TV and telephone operator in Venezuela, Inter. Even the Panamanian law firm suspected that it was being used for money laundry. Meanwhile, another firm of the group contracted works with the Chavista State.

Without human rights officers at the ports of entry or legal system that protects the refugee, Venezuelans migrating to the Caribbean island find relief from hunger and shortages. In return, they are exposed to labor exploitation and the constant persecution of corrupt authorities. On many occasions they end up in detention centers with inhumane conditions, from which only those who pay large amounts of money in fines are saved. The asylum request is a weak shield that hardly helps in case of arrest. Yet, the number of those who try their luck to earn a few dollars grows.

The network of intermediaries contracting with the Venezuelan Foreign Trade Corporation (Corpovex) to bring CLAP boxes seems infinite. In Sabadell, a town near Barcelona, a virtually cash shell company got 70 million dollars for outsourcing the shipment of food to Venezuela thanks to the administration of Nicolás Maduro, which buys the contents of the boxes at discretionary prices and without control. Last year alone, the government spent 2,500 to 3,500 million dollars, but only the leaders of the "Bolivarian revolution" know the actual figure.

The chemical analysis of eight Mexican brands that the Venezuelan government supplies to the low-income population through the Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP), gives scientific determination to what appeared to be an urban legend: it may be powdered, but it is not milk. The fraud affects both the coffers and the public health, by offering as food a mixture poor in calcium and proteins, yet full of carbohydrates and sodium.

Venezuelan Álvaro Gorrín escaped on his yacht in 2009 after the intervention of Banco Canarias, but he and his board members did not resign themselves to losing everything to the Venezuelan government. Between the support of an influential New York law firm and the expertise of Appleby to create companies in tax havens, the then fugitive from the Venezuelan justice drew a strategy to rescue something from the ruins.

In Venezuela, less than fifty military officers are entrusted the mission of administering justice to their military counterparts. But as the Government of Nicolás Maduro sends more political dissidents and insubordinate civilians to be tried in that jurisdiction the weakest flanks of a lodge of judges arbitrarily appointed by the Ministry of Defense, who have unclear merits and a clear willingness to follow orders, are more evident.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.