There is a legend in the mountain chain Sierra de Perijá that blames its felling on a transnational company. A journalist traveled the route of taro (locally known as ocumo) and after a trip through western Venezuela, he found that - contrary to official complaints - the root of discord is served in Bolivarian government markets.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Fried taro looks like Ruffles potato. It is identical. Its texture makes it turn immediately toasted when cooked in oil. It tastes similar to potato. Although it is totally white, it turns yellowish as the famous potatoes advertised by the exceptional Lionel Messi.

Anyone could say that taro is the raw material of Frito Lay's potatoes. Not surprisingly, the environmental authorities of Venezuela, together with the Azul Ambientalista organization, last year concentrated 2,000 people in three different cities to protest against the production of taro. There, the defenders of the forest directly blamed company Frito Lay for promoting —with no other reason than to enrich itself through the production of snacks— the deforestation of Sierra de Perijá, the northernmost of the Andes, which acts as a vegetable lung of Zulia state, north of the border of Venezuela with Colombia.

Things changed after that protest. In La Villa del Rosario, the town closest to the mountain chain, people say that 1,500 illegal Colombians returned to the other side of the border. The diaspora took place between July and August 2014, when the National Institute of Integral Agricultural Health of Venezuela (Insai) prohibited the distribution roadmap to traders of taro produced on the slopes of Sierra de Perijá. Those 1,500 men and women, accustomed to living in the countryside and who had fled the armed conflict of their country, planted the malanga (taro) plant in the acres of land they had conquered. But they left when the protests against cultivation began.

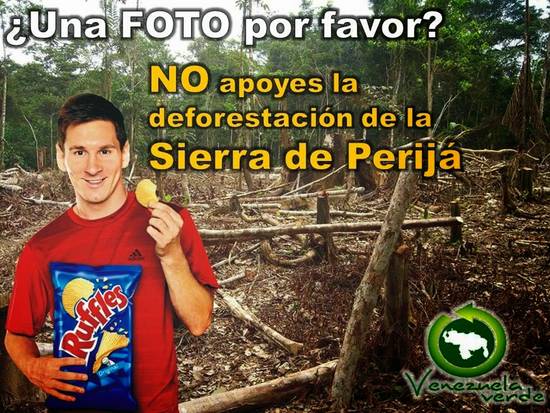

For environmentalists, it was a fight between David and Goliath, so they filled the web with montages where even Messi could be seen eating Ruffles with a deforested park behind. They also asked the Legislative Council of Zulia State a resolution to ban the cultivation and reported the news of the protest in all the National Government media, which at the same time did not spare in adjectives to spread the word that the subsidiary of Pepsico - with administrative headquarters in Torre Polar de Los Cortijos - was an enemy of the Lake Maracaibo basin.

The crusade by environmentalists yielded results: the production fell from 100 to 25 tons cubic feet in a week. Two names remained at the forefront of this battle. On the one hand, the "Sole Environment Authority of Zulia State", Lenín Cardozo, together with, Gustavo Carrasquel, president of the Azul Ambientalista organization.

"Yes, we received support from many people and managed to save many acres in the Sierra that were already corroded by the crop," explains Gustavo, with a python snake lying beside him inside a square fishbowl. "Everyone was against Frito Lay".

-How

did you confirm that Frito Lay promoted the cultivation?

-The producers. They

told us that they received money from someone wearing the uniform.

- Is there

any way to confirm that Frito Lay bought or promoted the crop?

-We rely on at

least 90 testimonials. They all said that a man in Frito Lay's uniform gave them

money to produce.

When one arrives at La Villa del Rosario and asks about the "malanga growers", they all point their fingers to the home of Edicso Acosta, in San José area. There, on a dead end street, her mother - an old woman of over 70 years old - sits down to grind coffee by hand right next to a Kodiak truck parked in what is left of the yard, under a mango tree. There are 14 sacks of taro, approximately 700 kilos (154 lb), around that trunk, which have been out in the sun for over a week and are still fresh to eat.

Edicso has all the appearance of a field producer: torn clothes, plastic boots, and a hat. His role is basic. He buys everything he can from the producers and then resells it in the wholesale markets in the center of the country. Producers look for him because, when they do not have money, he finances the production with the only condition that they sell it to him. He always wins.

Prosperity is obvious. He has several trucks and employees. There is plenty for him to live and produce, and although there was a considerable decline in 2014, he never stopped selling the merchandise. "When the Colombians left, we had no producers," he says. "Only a few began to produce. I refused to leave this because it is the only thing I know how to do."

To reach the crops, you have to travel almost vertical miles of sand road, barely three meters (9.84 ft) wide between the wall of the hill and the cliff. Edicso arrives at these allotments on a small Toyota truck like those used by Islamic State terrorists on the other side of the world. He has six of those. And they are all his.

You can see the taro crops around the mountain chain walls, small plants with large heart-shaped leaves. Based on Edicso’s experience, the species was brought from Colombia, where they call it malanga, and it cannot compete with the Chinese taro produced in the east of the country, or the Venezuelan taro, whose fields spread throughout Portuguese state. Such crops are all along the dirt road of the Las Lajas area, which has a winding river around the road. Las Lajas is one of the tributaries feeding Los Tres Ríos, the largest water reservoir in Zulia state, which supplies its capital, Maracaibo, with a population of over 2 million inhabitants.

When

the crop is ready, producers leave the sacks on the edge of the dirt road

waiting for Edicso’s trucks. Their men pick them up and drive them to La Villa

del Rosario, where they leave in another truck bound for the states of Lara,

Aragua and Trujillo. For the authorities, it is an illegal activity; hence,

Edicso spends about 50,000 bolivars on each trip, to pass the check points on

the road.

The struggle of Azul Ambientalista is clear. Based on a study by the Environmental Secretariat of Zulia state, they warn that there are less than half of the 200 tributaries registered in the mountain chain in 2000. The investigation showed that at least 6,000 hectares (14826.32 acres) were affected, which already predicts a hydrological crisis in the region due to the drought of the Lake Maracaibo basin.

Although biologist Miguel Pietrangeli does not know whether or not Frito Lay is the promoter of the production, he is against that crop because it is a tuber that erodes earth. Furthermore, it produces landslides when it rains because it is a plant planted on the slopes.

An official of the National Parks Institute, who supported the protests and deforestation allegations, also point the now well-known taro cultivation as the culprit of the deforestation of over 8,500 million hectares (over 21 million acres) of the national park. He declared on condition of anonymity - on the other side of the telephone - that most producers were aliens and that there are no major censuses. But he insisted in leaving his name out of these lines. He did not even wanted to be mentioned as a public official, because those figures -the ones he repeats and keeps on his computer- are not from Inparques, but from Lenín Cardozo…

But Lenin Cardozo is not there. He left the country. Now he lives with his wife in Canada and ceased to be the "sole environment authority". Since March 2015, he has been the Environment Secretary of Zulia state with a leave on health grounds.

The environmental biologist and professor of the Faculty of Sciences of Universidad del Zulia, Miguel Pietrangeli, believes that the public official must give the explanation and that is why he gives the clue to solve this crossword puzzle: "But talk to Gustavo Carrasquel (the president of the Azul Ambientalista ONG), he is his brother ". Although with different surnames, the Frito Lay scandal seems to have come from the same family.

Edicso assures that in the Sierra they use taro to make porridge. They also fry it, cook it and bake it. It is a source rich in proteins according to the National Institute of Nutrition, which qualifies it as important after the first six months of a baby's life. It is also included in the menu of shelters dependent on the Ministry of Women and the School Feeding Program of the Ministry of Education.

Based on the 2014 Annual Report of the Ministry of Agriculture and Land, last year’s taro production was 94,904 tons, while in 2013, it was 84,081 tons. Edicso takes about 40 tons of that total in his truck. He left on Saturday night from La Villa el Rosario in Zulia state without the distribution roadmap granted by the National Institute of Integral Agricultural Health of Venezuela. Hence, his taros could be confiscated at any time.

One out of the 400 hectares (988 acres) that affect the rest of Sierra de Perijá was necessary to fill that truck. According to his calculations, 10,000 plants are planted out in one hectare (1.47 acres), which produced 70 tons taro. The environmentalists have grounds to complain.

Many of these sacks are sold in the wholesale market of Barquisimeto (Mercabar), Lara state, in western Venezuela. There, Edicso unloads the product in the stall of Macario Reañe, who has been buying and selling vegetables for over nine years.

Reañe affirms that his customers are small greengrocers who buy some sacks. I wish, he says, that Frito Lay approaches me to buy everything at once to make a profit soon and buy a new truck the next day. But it's not like that. "They also sell in Trujillo and Maracay. They might buy there, I do not know," he says. "The truth is that Frito Lay does not come here."

Lenín Cardozo Parra, the Secretary of Environment, Land and Territorial Planning of Zulia state, has a long history as an environmental defender in the region. In the early 80’s, he founded the Azul ambientalista group, which is a reference in the region today. Graduated from Universidad del Zulia, he was Secretary of Public Works, Infrastructure and Environment during the two administrations of Francisco Arias Cárdenas. He was also president of the Engineers’ Association of Zulia state, and in the last three years, he has been promoting a regional government based on ecotourism.

Thus, he created some tourist routes in the west of the country. Several routes include a visit to a newly discovered cave a few kilometers from Sierra de Perijá. But he has his detractors. For example, Lusbi Portillo -of the NGO Homo Et Natura, who has not stopped accusing him for having double standards, as he pays for pages in color in local newspapers criticizing the cultivation of taro in the foothills of Sierra de Perijá, while ignoring the exploitation of coal in other areas of northern Zulia state.

After a few weeks, Cardozo answered -from Canada- the calls asking for an answer to this report. He said that he remains at the helm of the Secretariat of Environment of Zulia and that the assistant secretary, Normando González, now has his functions but does not hold his position.

He reiterated that Frito Lay is the company that encourages deforestation in the area and added that the product of discord no longer ends in Valencia, in the snacks factory of the multinational Frito Lay due to a resolution he asked to be issued before the Ministry of the Environment, implemented in the military checkpoints arranged on the road between Zulia and Carabobo states.

In that company, however, there is another side of the story. Although hermetic, the subsidiary of Pepsi Cola in Venezuela warns that they do not even have processing plants in the state of Carabobo. They affirm that their plants are in Santa Cruz de Aragua and La Grita, Táchira state. There they process potatoes: they peel them, fry them and season them with sodium, saturated fats, gluten, vegetable oil and other essences such as cheese and onion.

All these products are registered by the Ministry of Health. It is with good reason that the two plants were inspected last year at the request of Frito Lay itself. And they did it to play safe, they say, but also planning a lawsuit against Cardozo and the NGO Azul Ambientalista. Hence, the company published a statement signed by José Enrique Zambrano, the legal director of Interinstitutional Relations, denying the accusations, requesting evidence and reserving any legal action.

Another of Edicso’s routes and all its equipment end in Aragua state, in the Wholesale Market of Maracay, about 50 kilometers (31 mi) from Caracas. It is a space located in a small industrial area that is heavily guarded and sells products for members only. Not everyone can go there and buy, only those with businesses. Edicso has the opportunity because he downloads a good part of its sacks of taro at least twice a week in the warehouse of Wilfredo Aponte, a businessman who has more than 18 years in that place and ensures that he buys at least 15 tons of taro a week, which is about half of the weekly production in the mountains.

At least 10 of those 15 tons are acquired by Pedro Benetti, an old buyer who mainly sells to the Corporation of Supply and Agricultural Services (CASA), a unit of the Ministry of Food with headquarters in the same Wholesale Market of Maracay.

Benetti did not want to talk. His assistant, Raúl, asked why we were looking for him and promised to have an answer, but then, he never answered the phone calls.

According to the National Register of Contractors, Pedro Omar Benneti Novo is the general manager of a food distribution company and three other cooperative associations dedicated to the same sector. Two of them are even located in La Morita de Turmero sector, where the market that serves the city of Maracay is located.

Both cooperative associations registered Mercal - the largest food distribution network of the Venezuelan government - as their VIP client. Not without reason, a press release published by the same agency in April 2015, explains that the Benetti cooperative associations are responsible for the transportation of food throughout Aragua state and that these items come from several states of the country.

Wilfredo explains that Benetti is one of his best clients, because he distributes to the Mercal network, the shelters and the School Feeding Program. Week to week it takes, on average, 10 tons, which translates into more than 540 tons of taro, representing at least seven hectares and a half (18.5 acres) of the 400 that have done so much damage in Sierra Perijá. It seems that the Perijá deforestation does not end in Frito Lay but in the government food network.

(*)This report was developed along the Investigative Journalism Specialization Course, dictated by the Press and Society Institute (IPYS) in partnership with Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (UCAB).

Adrián Perdomo Mata has just entered the list of sanctioned entities of the US Department of the Treasury, as president of Minerven, the state company in charge of exploring, exporting and processing precious metals, particularly gold from the Guayana mines. His arrival in office coincided with the boom in exports of Venezuelan gold to new destinations, like Turkey, to finance food imports. Behind these secretive operations is the shadow of Alex Saab and Álvaro Pulido, the main beneficiaries of the sales of food for the Local Supply and Production Committee (Clap). Perdomo worked with them before Nicolás Maduro placed him in charge of the Venezuelan gold.

Gassan Salama, a Palestinian-cause activist, born in Colombia and naturalized Panamanian, frequently posts messages supporting the Cuban and Bolivarian revolutions on his social media accounts. But that leaning is not the main sign to doubt his impartiality as an observer of the elections in Venezuela, a role he played in the contested elections whereby Nicolás Maduro ratified himself as president. In fact, Salama, an entrepreneur and politician who has carried out controversial searches for submarine wrecks in Caribbean waters, found his true treasure in the main social aid and control program of Chavismo, the Clap, for which he receives millions of euros.

While the key role of Colombian entrepreneurs Alex Saab Morán and Álvaro Pulido Vargas in the import scheme of Nicolás Maduro’s Government program has come to light, almost nothing has been said about the participation of the traders who act as suppliers from Mexico. These are economic groups that, even before doing business with Venezuela, were not alien to public controversy.

Even though there are new brands, a new physical-chemical analysis requested by Armando.Info to UCV researchers shows that the milk powder currently distributed through the Venezuelan Government's food aid program, still has poor nutritional performance that jeopardizes the health of those who consume it. In the meantime, a mysterious supplier manages to monopolize the increasing imports and sales from Mexico to Venezuela.

Turkey and the coastal emirates of the Arabian Peninsula are now the homes of companies that supply the main social -and clientelist- program of the Government of Venezuela. Although the move from Mexico and Hong Kong, seems geographically epic, the companies has not changed hands. They are still owned by Colombian entrepreneurs Alex Nain Saab Morán and Álvaro Pulido Vargas, who control since 2016 a good part of the Import of food financed with public funds. Around the world for a business.

Since the borders to Colombia and Brazil are packed and there is minimal access to foreign currency to reach other desirable destinations, crossing to Trinidad and Tobago is one of the most accessible routes for those in distress seeking to flee Venezuela. Relocating them is the business of the 'coyotes' who are based in the states of Sucre or Delta Amacuro, while cheating them is that of the boatmen, fishermen, smugglers and security forces that haunt them.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.