Venezuela sought to build an appliance factory to manufacture white goods for all homes by 2025. It ended up importing them from the factory funder itself: China’s Haier.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

On 25 November 2011, President Hugo Chávez directed the televised ground-breaking ceremony for the Haier household appliance industrial complex from the Miraflores presidential palace.

A group of Chinese executives seated in the palace were attentive to the translation coming through their headphones as they watched both the Venezuelan president and the start of construction work on their screens.

Outside the studio, in San Francisco de Yare, a town in northern Miranda state, 77 kilometres west of Caracas, Yuri Pimentel, then Venezuelan deputy minister of Planning, acted as master of ceremonies for what was meant to be an auspicious moment. There were four shovels buried in the sand, a red ribbon on each, and a foundation stone in the middle. A representative of the Chinese electrical appliance company stood alongside him.

In the short to medium term, the project promised technological independence so that Venezuela could manufacture its own ‘white goods’ - domestic appliances that include washing machines, cookers, refrigerators, and air conditioners - all at low cost for poor Venezuelan households. No one would ever have to wash by hand again. Nor would they ever be too hot. Much less would food be lost due to lack of refrigeration. So went Chávez’s orders.

A decade later, Yare was left with a blank promise rather than white goods.

As it turned out, China paid in and got its change. The loans from Beijing to finance the construction of the factory were used to buy precisely the same finished products that it was supposed to manufacture. And from China too.

The agreement that led to starting work on the factory was signed three years earlier. On 23 September 2008, it stipulated a joint venture between Venezuela and Haier Electrical Corp Ltd. Haier, which has its headquarters in the city of Qingdao, is itself a joint venture - with both Chinese and German capital - but in practice it operates as one of the hundreds of Chinese state-owned companies and receives the preferential treatment reserved for them.

The partnership also aimed to foster technology transfer agreements and supply contracts to "achieve the country's independence" in the medium term by producing and developing household appliances on Venezuelan soil.

But from the beginning of 2009, signs began to emerge that the letter of the contract might already be dead.

A report dated 11 February 2009, issued by the Ministry of Light Industries and Commerce and the Venezuelan Corporation of Intermediate Industries (Corpivensa), warned that Haier representatives had 'expressed reservations in providing the information required to formulate the project'.

The document is one of a number of leaked Chávez government papers from 2009-12 that Armando.info has accessed and which, in alliance with the data team of the Latin American Centre for Investigative Journalism (Clip) and with additional reporting by Diálogo Chino, form the basis of the series Venezuela’s dance with China. The series analyses various projects agreed between Caracas and Beijing.

The February report reveals the first doubts on Venezuela’s side that cast a shadow over the progress of a plan that, as with many others, started with so much optimism.

The agreement aimed to fill equipment shortfalls in the homes of low-income Venezuelans. The preliminary draft of the plan, presented to President Chávez, diagnosed that at the time of its drafting in 2009, 16.8% of the population did not have a refrigerator, 81.5% did not have an air conditioner and 45.7% did not have a washing machine, according to data from the Venezuelan National Statistics Institute (INE).

The goal was to bring the numbers of households without a refrigerator down to 4%, those without air conditioning to 19% and those without washing machines to 11% by 2021.

To achieve this in just eleven years, the Chávez government calculated that it would need to produce 488,555 refrigerators, 396,609 air conditioners and 489,555 washing machines at the new plant. If the rate were maintained, no Venezuelan household should be left without its white goods by 2025.

But just as the document was explicit and ambitious in its description of the binational project’s targets, it was vague in its reference to what was expected of the Chinese counterpart.

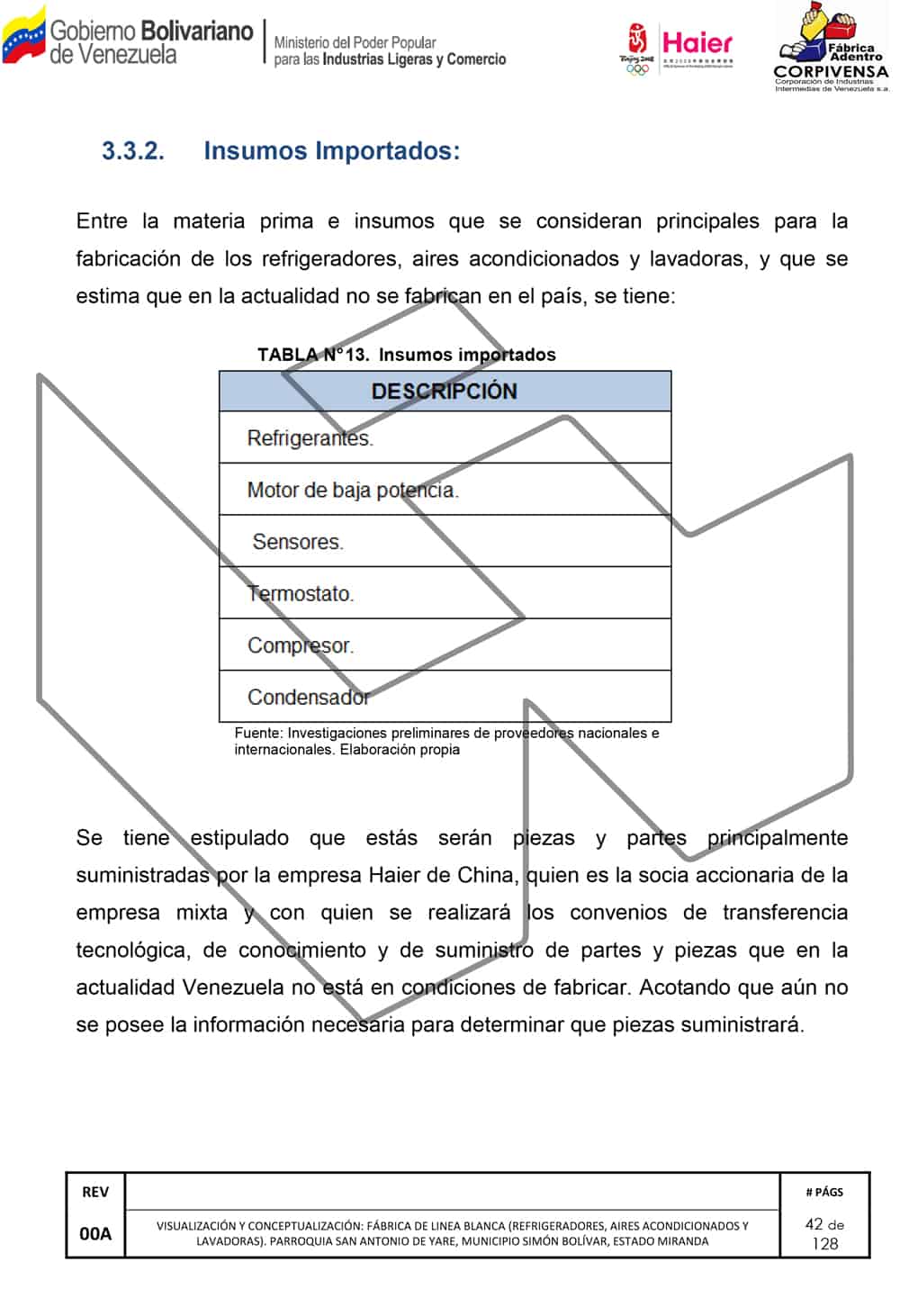

In 2009, the project barely sketched out what the function of the factory was, and tentatively acknowledged that it was not clear what the Chinese would provide: "It is important to note that, to date, Haier representatives have not provided information on the characteristics and physical properties of the raw materials and inputs to be used. Therefore, a further study will be required to determine new local suppliers," the plan reads.

Among the supplies to be provided by the Chinese company should be refrigerants, low-power motors, sensors, thermostats, compressors and condensers, the report authors wrote. These would be some of the "parts and pieces mainly supplied by the Chinese company Haier, which is the shareholder of the joint venture and with whom the agreements for technology transfer, knowledge and supply of parts and pieces that Venezuela is currently unable to manufacture will be made". However, it also notes that "the necessary information is not yet available to determine which parts will be supplied".

Despite these doubts, on 18 February 2009, eight days after the preliminary report was submitted, Corpivensa proceeded to sign the agreement with Haier on behalf of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela.

The document was remarkably ambiguous about the technology Haier would actually transfer to Venezuela. In the end, the Chinese company managed to sell more than US$750 million worth of finished household appliances to Hugo Chávez's government.

In 2010, the supply of Haier's ‘white line’ of goods helped Chávez and his political party, the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Psuv) to win parliamentary and regional elections of that year.

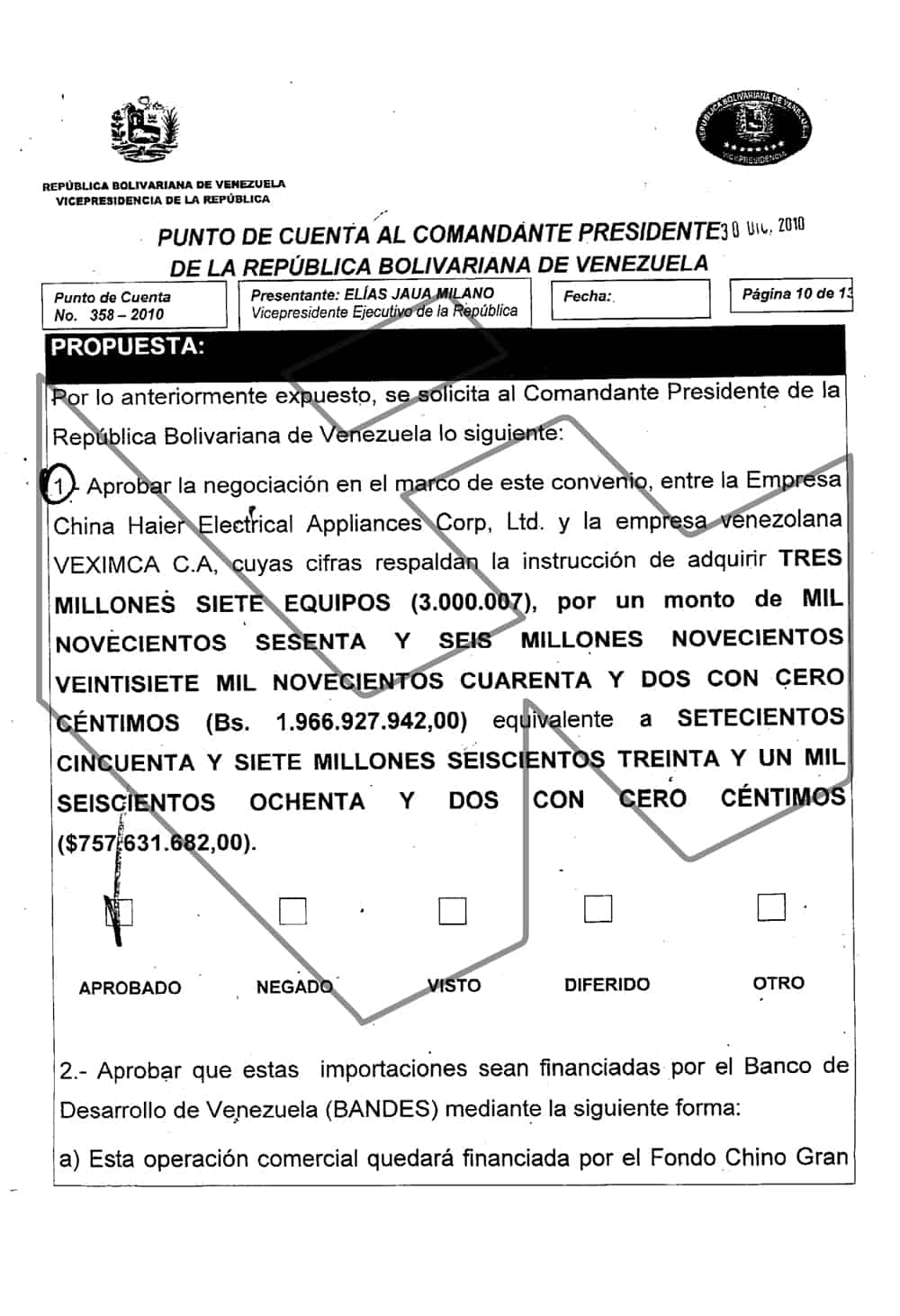

Then vice president Elías Jaua Milano proposed importing 19,672 containers with 3,000,007 household appliances, including gas heaters, televisions, DVD players, gas cookers, air conditioners, dryers, washing machines and refrigerators. In total, the purchase cost Venezuela $757,631,682, according to the contract seen by Armando.info that Giuseppe Yoffreda, president of the Venezuelan company Venezolana de Exportaciones e Importaciones C.A. (Veximca), signed with Haier Electrical Appliances Corp. Ltd. on 30 December 2010.

The amount was to be financed with resources from the Large Volume and Long Term Fund (FGVLP), a second body created in 2010, which along with the Venezuelan-Chinese Joint Fund, active since 2007, managed the China loans. FGVLP served to fund the ‘Mi Casa Bien Equipada’ (My Well-Stocked House) plan. As part of this social project, the small state-run markets, Mercal and Pdval, created by the Chávez government to sell food at low prices, would also sell the appliances. As part of the scheme, household appliances would be offered at prices of between 40% and 80% below those of private retailers.

In 2011, a washing machine made by brands such as LG, Samsung or Whirlpool ranged from 3,000 bolivars (US$697, according to the exchange rate of the time), while a Haier brand could be bought for half the price, just 1,472 bolivars ($342). A refrigerator of a competing brand cost around 5,000 bolivars ($1,162), while a similar one from the Chinese company cost 2,628 bolivars ($611). Credit, sometimes with no interest, enabled many purchases.

The Chávez government also offered credit through public banks to state employees to finance their purchases. Specialised state institutions, such as the People's Bank or the Women's Bank, offered loans to pensioners and poor families, respectively.

Haier products arrived in containers from China and were sold cheaply just as the construction of the Haier factory in the Valles del Tuy began.

The industrial park was built by another Chinese company: China Railway 9th Group Co, a subsidiary of the state-owned giant China Railway Engineering Corporation (CREC), which was in charge of other projects in Venezuela. These included the ill-fated Tinaco-Anaco Railway. Steel manufacturer Henan Tianfon Group, from Henan province, also participated in the project.

Proof that the Chinese government attached importance to the appliance factory is that the inauguration of the plant in September 2012 featured on the website of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (Sasac), the powerful government commission that oversees all state-owned enterprises.

In fact, it was precisely the kind of project that coincided with goals that China set out for its relations with Latin America in its Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ 2008 'white paper' policy document. Beijing identified "strengthening exchanges with Latin American and Caribbean countries in industry" as a strategic matter, as well as "sharing best practices in each other's industrialisation process, and promoting and deepening practical cooperation".

In the end, Haier invested what would amount to just 6.7% of the eventual revenue it earned from the sale of imported appliances in the manufacturing project, according to official documents. The deal with Chávez brought the Chinese company around 3.6% of its 2010 sales, as Haier announced global revenues of US$20.7 billion for that year.

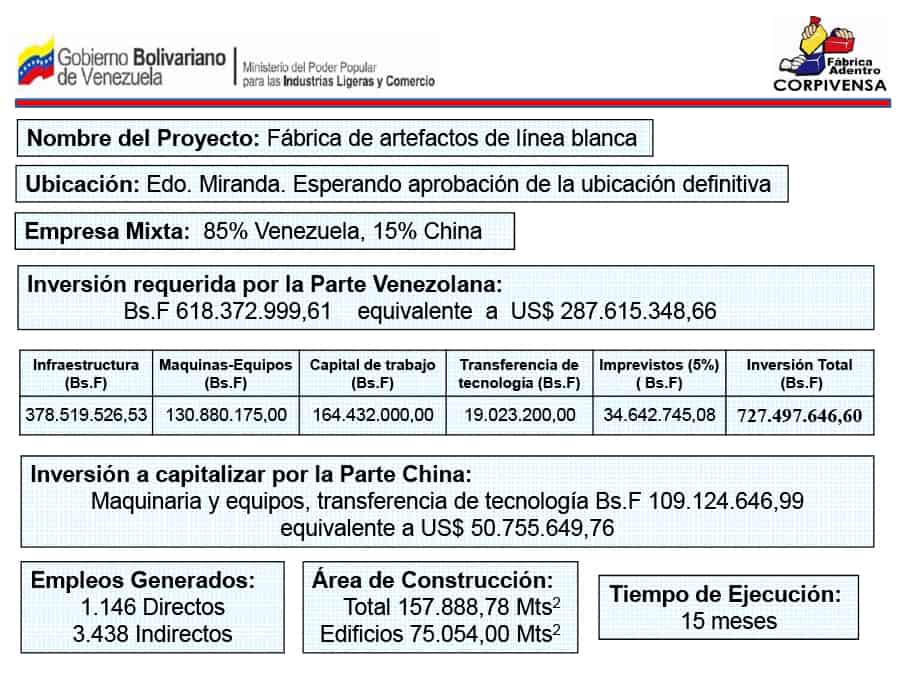

This suggests that the Chinese company was more enthusiastic about selling the finished appliances to Venezuela than it was to help the country set up its own factory. The initial investment for the factory was estimated at just over 727 million bolivares, some US$287 million, according to the official exchange rate at the time. Of this, Haier would contribute only $50 million. The rest came at Venezuela’s expense.

The simultaneous deals for the factory and the purchase of finished household appliances, which had the backing of both governments, ended up favouring Haier and leaving the Chavista dream of turning Venezuela into a manufacturing power in tatters.

Nor did it bring jobs to the struggling inhabitants of San Francisco de Yare, a commuter town outside Caracas. The plant was supposed to generate 1,146 direct jobs and another 3,438 indirectly. In the end, it created far fewer.

Although the plant managed to get up and running in 2012, by November 2019, seven years after its inauguration, it employed just 237 people and had barely produced 5,000 fridges. That same month, the already meagre production was halted due to a lack of gases and refrigerants, precisely two of the materials that the Chinese partner was supposed to supply, factory workers told Armando.info. It has not been operational since.

What was left of the factory after its inefficient planning was wiped out by the deepening economic crisis and runaway hyperinflation that hit Venezuelan economy. All that remained of the Haier factory were grandiose promises and 160,000 hectares of a development that today lies disused.

Perhaps the ground-breaking ceremony was a premonition. "The Chinese dragons have joined forces with the devils of Yare. Dragons with devils, what will come out of that?" Chávez joked on 25 November 2011, in reference to the ritual dance that San Francisco de Yare and other towns in northern Venezuela perform on Corpus Christi day.

As is tradition, the ceremony was supposed to involve Chinese dragons dancing around the inaugural plaque, signaling the beginning of a great project to assemble household appliances.

The cultural event did not take place. Not a single dragon was present during the ceremony. Chinese fortune would never come to Venezuela.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.