Two entrepreneurs from Peru, Yosef Maiman and Sabih Saylan, participated as intermediaries in the irregular payments of Odebrecht, through offshore structures, to the former president of that country. They are part of a "shell companies" structure built by Mossack Fonseca, as shareholders of the private cable TV and telephone operator in Venezuela, Inter. Even the Panamanian law firm suspected that it was being used for money laundry. Meanwhile, another firm of the group contracted works with the Chavista State.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

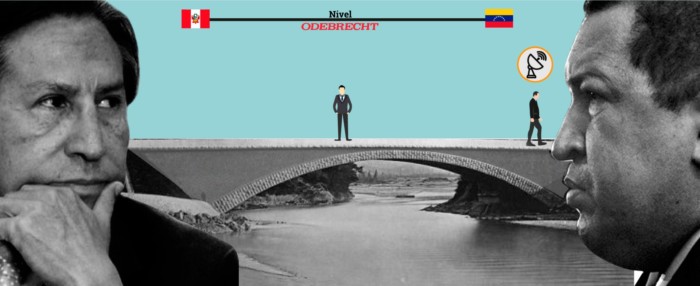

At the end of the government of Alejandro Toledo (July 2001 - July 2006) in Peru, his difficult relationship with the then Venezuelan leader, Hugo Chávez, reached the most critical point. In May 2006, Toledo would eventually withdraw his ambassador in Caracas due to, as he said, a "persistent and flagrant interference" by Chávez in internal affairs.

Despite the diplomatic rift, and maybe without the presidents in Lima and Caracas and even the entrepreneurs themselves being aware of this, a business group continued being an interconnection channel between Toledo and Chávez.

key names of the group were those of Peruvian-Israeli entrepreneur Yosef Maiman and his right-hand man and compatriot, Sabih Saylan.

In June 2006, President Alejandro Toledo, as then established by the Peruvian justice, began receiving million dollar payments from the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht, through the bank accounts of three offshore companies controlled by Yosef Maiman.

Meanwhile in Venezuela, Sabih Saylan ?like Maiman, also investigated and charged in Peru for his role as an intermediary in the case of Odebrecht's bribes?was the administrator of the Merhav Group subsidiary. This conglomerate of companies specializing in the development of large-scale infrastructure projects was founded by Maiman in 1975, in Israel, and at age 72, he is still the president and director thereof. Merhav had been assigned the execution of several projects of the Venezuelan Government.

But that was not the only connection of the group ?that was an accomplice in Peru, as an intermediary, of the payments for which today former President Toledo is a fugitive from justice? with Venezuela.

They already had businesses in the Caribbean country, which they shared with the executives of one of the most important cable TV and telephone operators, Intercable (currently, Inter).

These businesses left no visible trace, saved for, ironically, the hermetic discretion of the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca.

On February 10, 2017, as is now known due to the leak of the so-called Panama Papers?originally received by the Süddeutsche Zeitung newspaper of Munich and coordinated as a journalistic project by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) of Washington DC?, a Suspicious Activity Report (SAR), intended for authorities against money laundering of the British Virgin Islands, circulated through the internal mail of Mossack Fonseca and triggered, undoubtedly late, the alarms inside the branch of the law firm in Tortola, capital of the archipelago and one of the most impenetrable tax havens in the world.

The memorandum warned about the activities of a group of offshore companies: Vision Investments Equities INC., Caribbean Pressing LTD., Latin American Group Investments INC., New Age Communications INC. and CIT Management Corp. It also mentioned the shareholders and beneficiary owners of the companies, Alberto Imar and Eduardo Stigol, both Argentinian, former director and president of Inter Venezuela, respectively; Leo Malamud, Maria Luisa Watson and, unsurprisingly, the aforesaid accomplices of President Toledo, Yosef Maiman and Sabih Saylan.

Particularly them - the report assured – were suspected of money laundering.

"They are allegedly involved with the Brazilian construction giant, Odebrecht S.A., and its petrochemical subsidiary, Braskem S.A.," warned the document, which was sent to the direction of the Financial Investigation Agency in the British Virgin Islands.

(Late) Money Laundering Alert

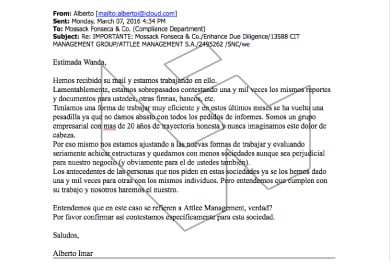

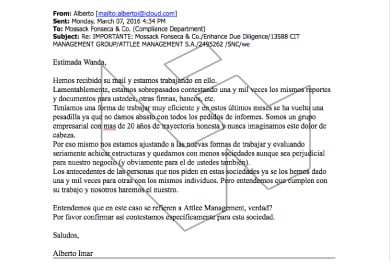

It was not the first time that the law firm's compliance officers took notice of this group of investors. In the first quarter of 2016, they learned firsthand of an email exchange with one of the protagonists, the Argentinean Alberto Imar; the "nightmare" they were experiencing as a result of the investigations on billionaire Maiman, the head of the group, and Saylan for money laundering, within the framework of the so-called Ecoteva Case; the criminal process in which they were involved with their friend, former president Toledo, and his family.

"We are a business group with over 20 years of honest history, and we never imagined this nightmare," acknowledged Imar, who led the communications of Inter companies with the firm, in an email sent to the Compliance Department of MF, on March 7, 2016.

What could have changed from the date of that confidence that the executives of Mossack Fonseca received with understanding to early 2017, when the law firm decides to report the distressed entrepreneurs?

Simple, Braskem, the petrochemical arm of Odebrecht and the largest company in the sector in Latin America, had just pleaded guilty in a Federal District Court in Brooklyn - one of the five counties of New York City - to conspiring to violate a Bribery law abroad. On December 21, 2016 Odebrecht agreed with US Department of Justice agents to pay a fine of $ 3,500 million - the largest ever required for a case of bribes abroad - to settle international charges that included payments to Brazil's state oil company and politicians, including former president Toledo.

Mossack Fonseca feared being dragged into this litigation in the United States of America.

"We noticed that Mossack Fonseca provided representation services to many, if not most, companies. We also noted that general Powers of Attorney were granted. Even though most companies were eliminated, can you confirm the resignation of our directors, when appropriate, and the revocation of the Powers of Attorney? In addition, can you say since when do we know that the client and his companies were being investigated as part of the Odebrecht scandal?" Questioned, on February 14, 2017, the CEO of MF in the British Virgin Islands, Daphne Durand, eager to get rid of those toxic customers.

Mossack Fonseca in the British Virgin Islands asked to update the position of the related companies they helped to create and which, in some cases, they were still related with.

Just a week before, she had received from Wendy Agard, from the Compliance Department of the Panamanian office, an email with the link of one of the reviews made about the investigation on the digital newspaper Ojo Público in Peru, revealing that entrepreneurs close to Toledo and under investigation by the justice system in that country had used companies created by themselves to make deposits and transactions that could be linked to payments of bribes.

Two days later, from Panama, Yakeline Pérez would send Durand a chart with the updated information of 15 companies registered between 1997 and 2015.

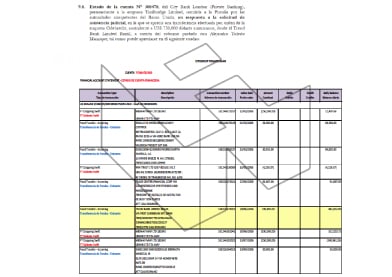

The Peruvian media placed special emphasis on one of the companies, Vision Investments Equities. They said, based on the first leak of the Panama Papers, that it "may be the most important offshore company" linked to Toledo’s operators Maiman and Saylan, and that in 2000, it managed almost 68 million dollars for the surplus of its assets [I1], which Argentines Stigol and Imar denied in interviews for this report.

Based on documents of the communications of the group with the Panamanian law firm that represented their companies, the also "suspicious" CIT Management Corp - according to the Suspicious Activity Report or SAR - was the owner of just over half of the shares of Vision Investments Equities, the other shareholders of which, in order of importance, were Maiman, head of operations of the Merhav Group, Leo Malamud, also Peruvian and Israeli-born, and Saylan.

According to the SAR, Vision Investments Equities, an investor in telecommunications companies, born in Panama in 1997, but domiciled since December 2015 in the BVI, was the only one of the five "suspicious" companies by February 2017 that had activities in Venezuela.

Vision was incorporated simultaneously with another Panamanian company, Digital Investments Associates, at the request of Bentata, a Caracas law firm, which according to Imar, was fulfilling orders from the law firm formerly known as Hicks Muse, then HM Capital Partners?a private company in the United States of America, specialized in leveraged buyouts? to create several companies for Inter in order to group partners and managers and give shares to senior managers.

One of such companies was Vision Investments Equities and the instructions to create it, drawn from Caracas by lawyer José Javier Briz Kaltenborn, required Mossack Fonseca not to include the directors of the companies, and that Powers of Attorney were issued for Mr. Saylan in the name of Digital Investments Associates, and another for Malamud, Imar and Stigol, and Isaac and Gustavo Zviklich, in the case of Vision Investments Equities.

MF issued the full and general Powers of Attorney, which allowed them to manage the companies "without any limitation," "anywhere in the world." Since 1998, at the request of Bentata, the Panamanian law firm began sending invoices for the maintenance of both companies directly to an office in the Ciudad Tamanaco Shopping Center (CCCT), in Caracas, addressed to Saylan, then vice president of Merhav -Maiman's company.

Venezuelan telecommunications company Intercable, now known as Inter, was born in 1996 in the city of Barquisimeto, western central Venezuela. Two years before, Alberto Imar had the first contact with Maiman's group, according to an email interview. "They asked me for a professional opinion about the project they had, together with other partners, to launch a subscription TV company in Venezuela." He was called like other executives with experience in the field.

Always, according to that story, Imar dragged Eduardo Stigol. Together, they made the market studies, the business plan and offered themselves as an independent management to carry out that project. They knew each other from Argentina and both had experience with subscription television, unlike Maiman who, according to Stigol, joined Inter as a shareholder "who did not understand this business" and put up "some capital" at the beginning. "Some" could have meant around three million dollars, as he recalls, a figure that considers "very small" for an entrepreneur "as big as he (Maiman) was at that time."

However, I did not consider him a "small investor." "He was a major partner, who made a small investment in a business in Latin America. He was going to wait for results in time. Unfortunately, the political condition in Venezuela did not allow results and he did not see them," said Eduardo Stigol, president of Inter.

When Intercable was born, it was still a year before Venezuelan Bentata’s lawyers contacted those of MF, but Stigol affirmed that "originally they were the same partners" of Vision Investments Equities, including Maiman. However, both he and Imar insist on dissociating themselves and Inter from Maiman, Vision Investments Equities and, in general, from any other company or business related to Maiman. They claim that they were never their employees or of any of their companies, that since 1998, he was a "minority shareholder" who never had "anything to do with the management of the company."

"I may had seen him (Maiman) five times in all my life. He had an executive, Sabih Saylan, who did visit Venezuela frequently at the beginning, in those years (late 90's), because he had other businesses, and he was the one who called me to ask how the business was doing. But for them, ours was a business where they were never involved, and I totally do not know what other businesses they had," says Stigol.

Imar, who is very active in communications on behalf of the Mossack Fonseca group, seconded Stigol, "We were totally oblivious to the other businesses of Maiman, in Venezuela and abroad. Our only connection was Inter, where he was a minority partner. We learned about the problems he had with Peruvian justice through the media, just like the rest of the world."

The owner of the Inter brand in Venezuela is Corporación Telemic C.A. Based on information from RNC (National Register of Contractors), in 2015, all the shares of Corporación Telemic C.A. belonged to a company registered in Luxembourg, Venezuela Cable Service Holdings, Ltd., and although it appears as dissolved since September 2015, Imar insists that it is still valid in another jurisdiction, but he does not specify which one, and that it still owns Corporación Telemic.

In what follows, the statements of Stigol and Imar do not agree. According to Imar, the owner of Venezuela Cable Service Holdings is Intercable Holdings, a company active in the Cayman Islands since February 2011. For Imar, the chain ends in Venezuela Cable Service Holdings. In any case, both agree that since 1998, the majority shareholder is a fund that is now leaded by US investor Tom Hicks -of the late HM Capital Partners- and a group of banks, including Citibank and Chase. Together they control 75% of the company. The remaining percentage of shares is divided among other shareholders, including original shareholders Stigol and Imar.

Until 2015, among the members of Corporación Telemic, owner of the Inter brand, there was a representation of the Maiman group, the group of the HM Capital Partners fund and the management of Imar and Stigol. Today, many are disconnected from the company. The owner of Telemic was a company currently inactive in Luxembourg, Venezuela Cable Service Holdings, which was in turn owned by a company of the Cayman Islands, Intercable Holdings.

Maiman would have completely separated from the company, according to Argentine entrepreneurs, who claim to have lost contact with him. But Stigol and Imar versions as to how and when Maiman distanced himself from the company have many inconsistencies.

In any case, as revealed in documents from the registry of the British Virgin Islands, which Armando.Info has access to thanks to the cooperation of the Investigative Dashboard, Vision Investments Equities was liquidated on June 12, 2017, a month after its closing was requested.

"Some shareholders would still be linked to Inter's business and others not. Maiman was one of those who decided to separate from this business. Thus, the shareholders who decided to stay did so outside Vision, the others disassociated themselves, and since Vision was only intended to represent them all together in Inter, it finally dissolved," says Imar, who says that neither Saylan nor Malamud, of the Maiman group, are current members of Corporación Telemic. Also others from his management group and some members related to Hicks' group had also disassociated themselves from the business. When they began to separate from Inter's business, most of the companies that had been created between 1997 and 1998 were liquidated.

According to Stigol, the separation of Maiman would have occurred due to health problems, not because of the corruption scandals surrounding the Peruvian entrepreneur.

The online portal of the Merhav Group of Maiman y Saylan still refers to Inter Venezuela as an undertaking under its "ownership or management." It highlights that the group "promoted and developed," as an investor, "the largest cable TV operator in the country."

And it is not the only project in Venezuela that they proudly display.

Works with the State

"In partnership with the Halcrow Group in the United Kingdom, Merhav implemented major water and sewage treatment projects with a total investment of $ 250 million," they affirm in the portal, referring to the work that Merhav developed in Venezuela for the Environment portfolio.

The Merhav Group, a conglomerate of companies specializing in the development of large-scale infrastructure projects that Maiman founded in 1975, displays on its website the investments made by the Group in Venezuela in terms of telecommunications and environmental sanitation.

According to the National Registry of Contractors (RNC), the Merhav Group’s company in Venezuela executed projects for different Venezuelan State agencies, under the administration of Saylan and the general management of an individual named Meir Gabay. Although it is now unable to contract with the State, in 2004, Merhav Venezuela provided technical and technological support in the inspection and chemical cleaning of the desalination plant on the main island of the Los Roques archipelago, a Caribbean paradise, at one hour by plane, north of Caracas.

In August 2006, the Group undertook two other projects, also contracted by the State. One project, through Fundación Propatria 2000, ?an organization attached to the Ministry of Infrastructure, now attached to the Ministry of the Office of the Presidency and Follow-up to Government Administration? to participate in the construction of the longed-for and controversial Acarigua - Barquisimeto highway, to be opened for the 42nd Copa América Soccer Championship, which took place in 2007, in Venezuela.

However, by the end of 2007, only 40% of the project was completed, as recorded in the RNC form. An environmental sanitation project, simultaneously undertook by the group through the State Government of Aragua, had the same percentage of progress.

However, another company claims responsibility for the execution of these works on its website, Mundo Kariña Ambiente C.A. The names of its partners are repeated in this plot, Gabay and a woman named Esther Pirozzi.

Mundo Kariña Ambiente C.A. claims on its website having executed since 2001 at least four projects for the Venezuelan Ministry of the Environment, in the states of Anzoátegui, Carabobo, Monagas and Falcón. It details a "wide experience" in the country since 1994, precisely when the Maiman group contacted Imar to talk about the Inter project.

In addition to the Acarigua-Barquisimeto highway, there are the expansion of the Barquisimeto-Cabudare Intercommunal Avenue and the construction of the canal bridge for the irrigation of 900 hectares of mainly sugarcane land, of the producers of the State of Aragua, in the central region of the country.

These and other projects were being carried out in Venezuela while the "criminal pact" - as the Prosecutor's Office in Lima has called it - was being developed in Peru. This pact allowed Odebrecht to transfer millions of dollars to the three accounts of Maiman, from where they were transferred to Confiado Internacional, and from this to Ecostate Consulting and Milan Ecotech Consulting to, finally and after the long journey, nurture the coffers of Ecoteva Consulting Group S.A., through which real estate was later acquired and real estate mortgages were paid to finally benefit former President Toledo.

All this is told by the Peruvian Prosecutor's Office in the request for the extradition of Toledo filed to Judge Richard Concepción Carhuancho, on February 19 of this year. Among the evidence contained in the 54-page document is Grupo Instrucontrol C.A., a Venezuelan company, the members of which are also part of Maiman's network in Venezuela.

Although they only appear in the RNC as flow meter distributors for the Venezuelan State, this company transferred $ 54,000 in connection with a "Valencia Project" to one of Maiman’s accounts, where the money of Odebrecht ended up, the account of the offshore Trailbridge. Until the closing of this report, we tried to obtain details about this project, but the only response was that the company had closed and that its owners left the country.

In one of the proofs of the extradition request of Peruvian President Alejandro Toledo, filed before judge Richard Concepcion Carhuancho, on February 19 of this year, appears a transfer for

$ 54,000 from a Venezuelan company to one of the offshore accounts of entrepreneur Yosef Maiman, investigated for the bribes of Odebrecht.

Without human rights officers at the ports of entry or legal system that protects the refugee, Venezuelans migrating to the Caribbean island find relief from hunger and shortages. In return, they are exposed to labor exploitation and the constant persecution of corrupt authorities. On many occasions they end up in detention centers with inhumane conditions, from which only those who pay large amounts of money in fines are saved. The asylum request is a weak shield that hardly helps in case of arrest. Yet, the number of those who try their luck to earn a few dollars grows.

The network of intermediaries contracting with the Venezuelan Foreign Trade Corporation (Corpovex) to bring CLAP boxes seems infinite. In Sabadell, a town near Barcelona, a virtually cash shell company got 70 million dollars for outsourcing the shipment of food to Venezuela thanks to the administration of Nicolás Maduro, which buys the contents of the boxes at discretionary prices and without control. Last year alone, the government spent 2,500 to 3,500 million dollars, but only the leaders of the "Bolivarian revolution" know the actual figure.

The chemical analysis of eight Mexican brands that the Venezuelan government supplies to the low-income population through the Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP), gives scientific determination to what appeared to be an urban legend: it may be powdered, but it is not milk. The fraud affects both the coffers and the public health, by offering as food a mixture poor in calcium and proteins, yet full of carbohydrates and sodium.

Even Diosdado Cabello has false followers. The Government of Venezuela has been able to measure itself in political cyberspace. Hence, it has created an authentic machinery of robots at the service of the governing party in social media that is mainly controlled by public officials and coordinated from ministries. This is the result of several studies, testimonials and applications that measure the "Twitterzuela" convulsion.

Venezuelan Álvaro Gorrín escaped on his yacht in 2009 after the intervention of Banco Canarias, but he and his board members did not resign themselves to losing everything to the Venezuelan government. Between the support of an influential New York law firm and the expertise of Appleby to create companies in tax havens, the then fugitive from the Venezuelan justice drew a strategy to rescue something from the ruins.

In Venezuela, less than fifty military officers are entrusted the mission of administering justice to their military counterparts. But as the Government of Nicolás Maduro sends more political dissidents and insubordinate civilians to be tried in that jurisdiction the weakest flanks of a lodge of judges arbitrarily appointed by the Ministry of Defense, who have unclear merits and a clear willingness to follow orders, are more evident.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.