More than 850 Mexican drug traffickers have been extradited to the United States. But then, when the work seems to be done, Mexico realizes that in just a few cases it investigated enough to seize the finances of the mafias. Now a new chapter threatens to sour the binational fight against drug trafficking: the claim the United States has made of the fortunes of the capos.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Part three | After the extradition of El Chapo Guzman, the United States Government announced that it would go after his fortune, calculated around $21.6 billion, as a result of drug sales for more than two decades. The announcement foresees a difficult picture for the Mexican State.

In addition to confiscating minimal amounts from the main drug traffickers' fortunes, and be compelled to compensate third parties for errors in these processes - as it has been demonstrated in this series of reports, drawn from more than 200 official documents obtained by information requests -, Mexico now faces an even worse consequence of its mess in the confiscations of organized crime assets: despite being the territory where those gangs traffic, kill and do business, Mexico can be left completely empty-handed. Of the fortune of El Chapo -which represents a quarter of the estate of Bill Gates, considered the richest this year in the world by the Forbes magazine- for example, Mexico may get nothing.

The situation has warned Mexican lawmakers, who are demanding that the government stop their extradition of drug traffickers to the United States if there is no negotiation in the return of their assets insured by the US administration. The losses for the Mexican state would be substantial.

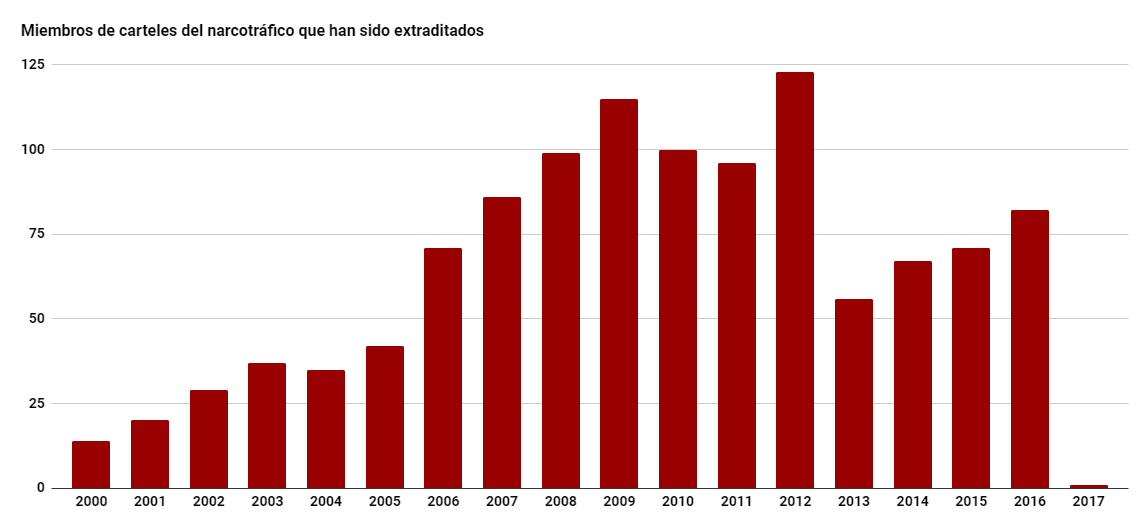

According to documents obtained by the Transparency Law, 1144 drug traffickers have been extradited to foreign governments between 2000 and 2017. Out of the 1064 extradited individuals that were sent to the United Stated, the majority, 853, are Mexican. Only 19 were sent to Spain and 10 to Canada, according to the reports of the Department of International Procedures of the Attorney General's Office.

"There is already an international agreement that regulates the type of relationship when a criminal is detained in Mexico and surrendered to the United States," warned Jorge Ramos Hernández, deputy chairman of the House Security Commission. "This agreement was signed seven years ago and it is still in force”.

“The government has been lethargic in starting a high-level round table between both Treasuries

The agreement provides a percentage of distribution of the insured or seized goods based on the level of participation of each country. "But it is not enough," said the legislator. “The government has been lethargic in starting a high-level round table between both Treasuries (those of Mexico and the United States) via the chancellery. The pace must be stepped up", he said.

Therefore, deputies of the National Action Party (PAN) - which was government in Mexico between 2001 and 2012 - now suggest that Mexico claims 50% of the resources that the United States secures from the extradited offenders. Is there any precedent for a return? "Negative, not just one," said the legislator, "the federal government is failing". He explained that a real effort was made with the deportation of Edgar Valdez Villarreal, the drug trafficker known as La Barbie, but the initiative did not succeed because Valdez had American citizenship, a rule that does not apply to return the money. He must have been Mexican.

October 2015 La Barbie, who was the operator of the Beltrán Leyva Cartel, and Jorge Eduardo Costilla Sánchez, The Coss, leader of the Gulf Cartel, were surrendered to the United States with 11 other criminals claimed by the said country. Despite the agreement with Washington, Mexico has no reports of the return of money or property insured to criminals for crimes such as organized crime, illegal deprivation of liberty, possession of cartridges for the exclusive use of the Army, crimes against health and qualified homicide.

Another case that reveals possible losses for the State is that of Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, leader of the Gulf Cartel. He was one of the 13 most wanted men of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of the United States, by which the American entity offered up to two million dollars of reward. Cárdenas was extradited to the United States in 2007.

In the list provided by the Attorney General's Office, it is reported that Cárdenas was confiscated 904 items, 43 vehicles, 21 real estate, 18 weapons, 37 jewels, 34,926 dollars and 146 dollars, among other items of lesser value. However, the Mexican authorities do not have information of what was confiscated by the United States.

However, the situation is different from the information that was made public by the media regarding to what was frozen from Osiel: 20 million dollars in property. The same happened to the drug trafficker Alfredo Beltrán Leyva, El Mochomo, who was sentenced to life imprisonment by a Washington Court. The US government confiscated properties valued at $529, million, according to press reports.

The empty Mexican coffers contrasts with the support Mexico has given to its northern neighbor in some investigations, says María Elena Morera, founder and president of Citizens for a Common Cause.

"Mexico and the United States have always worked together," she said. "Many known investigations there were conducted in Mexico. The most ethical prospect would be that the recovery of the goods would come to Mexico. However, that is not happening, there is no relationship with the United States on this issue", she said.

"Mexico has no strong research on this. I doubt that the United States will return something we did not investigate"

But although it cooperates, there is not always a financial stability in the Mexican investigations. These are cases such as those of Iván Reyes Arzate, a federal police officer, and Veytia Cambero, a former justice attorney for the state of Nayarit, in central-western Mexico. Both are related to drug cartels and were detained recently on US soil. "Mexico has no strong research on this. I doubt that the United States will return something we did not investigate", Morera said.

Amids the expectation created by compelling the United States to return the money secured from the narcos or the organized crime, there is a case that discards this possibility. In 2012, the US government sanctioned the British bank HSBC for $1.9 billion in civil forfeiture and fines for violating the Bank Secrecy Act and the Enemy Deal Act.

The bank was accused of transferring billions of dollars in support of Iran and Mexico's drug cartels to launder money through the United States financial system. "The investigation was carried out here in Mexico, but Felipe Calderón did not want to publish it. Instead, it was published by the United States and kept all the money", said Morera.

Meanwhile in Mexico, in the fourth annual government report, president Enrique Peña Nieto outlines the work carried out by the Financial Investigation Unit of the Ministry of Finance, which is responsible for combating money laundering, identifying illegal estates, simulations and illegal operations. In one section it points out: "Disarticulated criminal organizations: zero".

The former chavista governor of the State of Bolívar from 2004 to 2017 changed overnight from excessive media exhibitionism to low profile. His departure to Mexico completed the circle of the retirement plan he had been preparing while on civil service. He was now staying in the same country where the businesses of his daughter's husband flourished, which he had significantly fostered from his positions in Guayana. Now, with financial sanctions imposed on him by Canada and the United States, Francisco José Rangel Gómez prefers to stay under the radar.

Six out of every ten Venezuelan sex workers killed abroad since 2012 were in Mexico. In that country it is often about attractive girls who work as high-level company ladies or night-time waiters, businesses directly managed by organized crime. There are many clues that lead to the Guadalajara New Generation Cartel at the peak of this trade in people, with the complicity of others such as Los Cuinis and Tepito. Often the human merchandise becomes the property of capos and assassins, with whom he knows the hell of the femicides

A study by Mexican authorities confirms what the palate of the Venezuelans quickly detected: There is something odd in the Mexican canned tuna that comes in the combos of the Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP). At least three of the brands that the poorest homes have consumed in the country since March 2016, when the state plan was formalized, have high proportions of soy, a vegetable protein that although not harmful, it does not have the same taste and protein contribution of tuna. Behind the addition of soy there is an operation to reduce costs where all the intermediaries, handpicked by the Venezuelan Government to buy the goods, have participated.

Even though there are new brands, a new physical-chemical analysis requested by Armando.Info to UCV researchers shows that the milk powder currently distributed through the Venezuelan Government's food aid program, still has poor nutritional performance that jeopardizes the health of those who consume it. In the meantime, a mysterious supplier manages to monopolize the increasing imports and sales from Mexico to Venezuela.

Mexican authorities blame Venezuelan authorities for not verifying the quality of the products included in the combos for the Local Supply and Production Committee (CLAP). Even though the companies provided false information on the packaging, they wash their hands with bureaucratic technicalities and continue granting export permits. In Venezuela, no official wants to talk about it. For months, the Government of Nicolás Maduro bought and distributed among the poorest several powdered milk brands of the lowest quality.

In Mexico, there is a long tradition of cheating in the supply of dairy products packaged for social programs. Hence, it should not be surprising that the Venezuelan corruption had found in that country the perfect formula to include in the so-called CLAP Boxes a paste purchased at auction price as cow's powdered milk. For a mysterious reason, ghostly or barely known companies are the ones monopolizing purchase orders from Venezuela.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.