When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

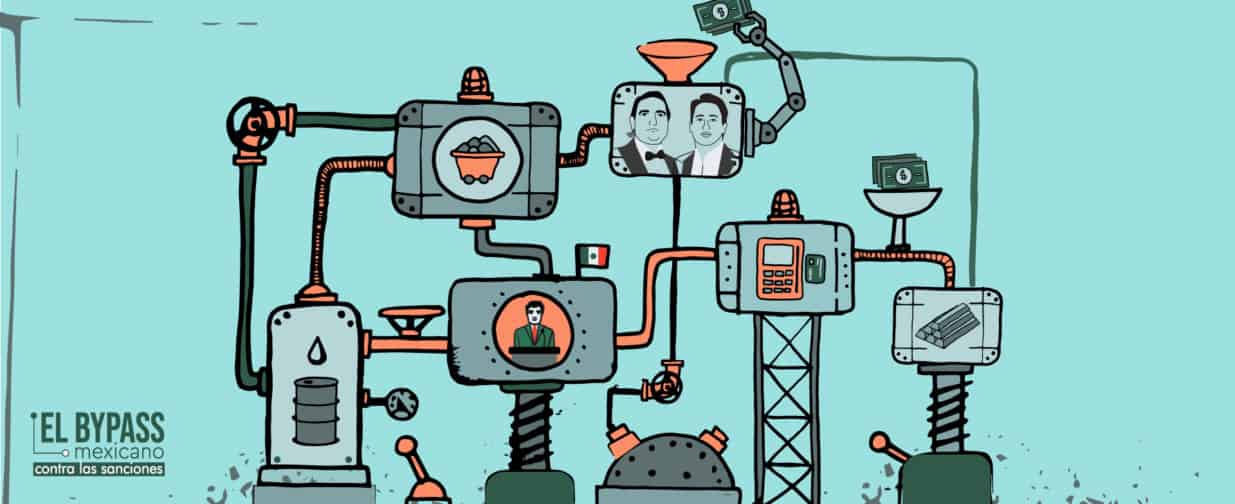

On March 7, 2019, Venezuela sank into darkness. What was supposed to be another blackout went on and on ⸺ one, two, five hours; one, two, three days... Amidst accusations of sabotage, the pro-Chávez government moved surreptitiously and resorted to the cooperation of some friends earned over decades, among them, a group of Mexicans. What seemed to be at first an approach to try to lessen the power shortages of a system undermined over decades of corruption and wrecked during the blackout, gave rise over the months to an international network used to try and sometimes successfully move huge amounts of oil, money and other resources, such as gold, coal and aluminum, disguised as humanitarian aid, constantly evading the U.S. sanctions ⸺ a scheme that involves dozens of people and companies, travels through almost thirty countries and transfers of money between tax havens. An investigation by EL PAÍS and Armando.info, based on a dossier with thousands of documents obtained on that network, reveals how the plot was hatched, thus allowing Chavismo to evade the sanctions of the greatest power on the planet and generate a shady yet a multi-million dollar business.

In April 2019, a month after Venezuela burned out into darkness, Vice President Delcy Rodríguez picked up the phone and contacted a group of Mexican businessmen that mastered the electricity sector. Originally, the idea was to see how they could bring power plants to Venezuela to ease the effects of the electricity crisis. However, from the first trip of the businessmen to Caracas, it was clear that their business intentions went beyond the acquisition of power generators. Several members of the Venezuelan government and operators of the Chavista leadership proposed what would become the germ of an international plot to generate an untraceable business. EL PAÍS and Armando.info have thousands of documents that, together with dozens of interviews―including some persons involved who requested to remain anonymous for fear of retaliations―attest to how this shady network was created and developed. A scheme that first exchanged oil for food and drinking water tankers, and then went on to collect money from oil exports through financial circuits outside the control of the United States of America. All those involved have a common link, Alex Saab, a contractor of Chavismo since 2011, who is said to be Nicolás Maduro’s front man, and is awaiting extradition in Cape Verde to be tried on money laundering in the U.S.

The origin of this network lies in the sanctions imposed on Venezuela since late 2014, mainly by Washington, under Obama’s and then Trump’s administration, to exert pressure on Maduro’s government in an attempt to stop the human rights violations, and openly forcing a political change that never came. Today, with Joe Biden recently installed in the White House, the sanctions are a bargaining chip in a potential negotiation between the opposition and the heir of Chávez to find a way out of the crisis in the country.

These exertions did reduce the leeway of Chavismo to do business with many companies, as they fear being the target of the U.S. Department of the Treasury. And PDVSA has been the bull’s eye of all the pressure, as it is the great source of foreign currency to Venezuela, the country with the largest proven oil reserves in the world, sanctioned since early 2019 by the Trump administration. After the state-owned oil company reached a point where foreign currency was scarce after the government spent it in all sorts of operations, Chavismo resorted to business transactions that allow them to pay with crude oil instead of money.

Delcy Rodríguez Gómez was key to activate the Mexican link. Along with her brother Jorge―current president of the National Assembly and former minister in several occasions-, they constitute one of the pillars of Nicolás Maduro’s government and a duo whose power has allowed them to displace Diosdado Cabello, as the unofficial number two of Chavismo. The former foreign minister and current vice-president scheduled in April 2019 a series of meetings between state officials and operators who were close to the Chavista leadership and a group of Mexican businessmen, including politician José Adolfo Murat, whom she knew from international forums of leftist organizations, like the one in Biarritz. With Simón Zerpa, the then Minister of Economy ―now in decline after accusations of disloyalty-, the possibility of an exchange of crude oil for tankers of drinking water and food was verbalized. Moreover, the minister asked the Mexicans whether it was possible to have a key post in Veracruz―the main port of Mexico from where companies linked to Alex Saab dispatched millions of low-quality and overpriced foodstuffs in CLAP boxes to Venezuela from 2016 to 2018―, which would allow large-scale shipments to get in and out.

The next meeting was between the Mexicans and Ricardo Morón ―sanctioned by Washington in July 2020, a businessman close to Nicolás Maduro Guerra, son of the President― and José Luis Sandoval, a PDVSA official. They raise the point of the need to exchange oil for white corn and durum wheat through Colombia ⸺the price and payment would be quoted in gold.

They also met with Omar Abou Nassif, brother of a businessman close to Delcy Rodríguez. Nassif suggested the Mexicans the possibility of moving some foodstuffs with transactions to be made through Hong Kong, assuring them that he counted on the collaboration of some suppliers in Mexico. Nassif’s statement was not trivial. He had also participated since 2016 in the CLAP scheme, precisely with companies registered in Hong Kong. Between 2016 and 2018, Alex Saab and his partner, the also Colombian Álvaro Pulido Vargas ―whose real name was Germán Rubio, but changed it after being involved in 2000 in a drug trafficking operation linked to the Bogota cartel― devised a structure of shell companies in Hong Kong, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. The Mexican businessmen benefited from these companies, some of which -as it has been proved- were linked to the new network that began to be woven in April 2019. The figure of Alex Saab also appears in those meetings in Caracas, since the Mexican businessmen met with one of his operators.

That series of contacts was taking shape upon his return to Mexico. Then, according to the reconstruction made through this investigation conducted by EL PAÍS and Armando.info, Joaquín Leal appeared on the scene ―a 29-year-old businessman, who the U.S. Treasury Department sanctioned since June 2020 for his business with Venezuela, and who, at that time, worked at Diversidad, the company of the above mentioned José Adolfo Murat, with whom he began to develop the business proposed to them.

In May 2019, Murat flies to Caracas with Leal. The Mexican businessmen meet again with Simón Zerpa. The aim is to materialize the operations that have only been discussed until then. Although Zerpa proposes to the Mexicans to receive direct payments in rubles or euros, the formula adopted is the exchange of oil for food and drinking water tankers.

The formula selected that they would implement a month later without Murat, only with Leal, as counterpart, implied that the Venezuelan party would ask a third actor to pay the Mexicans a 70% advance in euros. There is no account number of the recipient of the payment in either of the two contracts of the operation amounting to 200 million euros. “To the competent bodies,” it is the peculiar formula used in both cases, which also states that this payment may be made “in installments” and there is the possibility of terminating the contract within 90 days. Under the contracts, the remaining 30% of the payment “will be processed by buyer through competent financing entities,” and nothing else is said about the person referred to.

After signing the trade agreements, Leal sought advice and was responsible for finding the trucks and coordinating the transfer of the food from Mexico. He also negotiated the price of oil with his Venezuelan contacts. In the emails he portrayed himself as the legal representative of Libre Abordo, the company with which the Venezuelan government made the deal. After closing the deal, the Venezuelan oil company sent a series of invoices to Libre Abordo “to the attention” of Olga María Zepeda Esparza, director and partner of the company - currently sanctioned by the U.S. - detailing the equivalent in barrels of oil and the millions of euros that the oil company demanded as payment to the Mexican firm, in addition to the barter for food and products in kind. For example, an invoice dated June 19, 2020 for 32.9 million euros (equal to 36.3 million dollars at that time) states that the destination of the oil was the port of Singapore.

The oil-for-food and water tanker operation was the trigger for the U.S. Department of the Treasury to sanction Libre Abordo, Joaquín Leal and Zepeda Esparza a year later, in June 2020. Then, Mexico’s Financial Intelligence Unit (UIF), headed by Santiago Nieto, launched an investigation to follow the money trail. The results, however, are negligible. Just last May 18, the UIF filed a complaint with the Attorney General’s Office―to which we have had access for this report―and requested the seizure of about a hundred accounts of Libre Abordo, Leal, Zepeda Esparza and his mother, Veronica Esparza, a partner in the company.

The trip in that spring was the only one that Murat and Leal made together to Caracas. Murat, consulted for this report, assures that he left the business in Leal’s hands when he returned from Venezuela. When Leal told Murat that the Venezuelan party insisted on including an oil swap as part of the deal, Murat asked him not to go ahead. “I told him there were U.S. sanctions and we couldn’t get into that mess,” he said. According to Murat’s version, he broke off the relationship with Leal months later, in 2019, upon realizing that despite the warnings, Leal had continued with the business from Libre Abordo.

On the other hand, Leal did not want to give his version or an answer to the interview requests for this investigation.

The Venezuelan vice president was also asked to give her version, but no response was received at the time of closing this release.

From the operations for tank trucks and corn, Leal, together with Alex Saab, organized a secret network from Mexico at the service of Maduro’s government for the country to sell Venezuelan oil regardless of U.S. sanctions. In an attempt to hide the money trail, he created dozens of companies and weaved a network of financial partners in some thirty countries. The scheme is connected to entities worldwide, some offshore, in Switzerland, Luxembourg, Malta, Curacao, United Kingdom, Sweden, Norway, Greece, United States of America, Singapore, Bangladesh, China, Malaysia, Mexico, among other countries in Europe, Asia and America and tax havens; for example, the Isle of Man and the British Virgin Islands.

The modus operandi reconstructed in this investigation shows that the provision of humanitarian aid was just a pretext. The Mexican side shipped the products in kind and PDVSA paid them with oil and logistics to take it out of the country in ships. However, behind this operation, a more complex one was hidden, generating millions in profits for those involved through the resale of crude oil at below-market prices, with money that eventually returned to PDVSA as payment for the merchandise. The Venezuelan oil company ended up charging the invoices issued to Libre Abordo against accounts in Russian banks, such as Gazprombank and Evrofinance Mosnarbank. Thus, they were able to carry out the transactions outside the U.S. banking system, without involving U.S. citizens. The documents at hand for this investigation show that the oil deals were in place from November 2019 to May 2020. In most cases, food barter was set aside and oil was sold directly to Mexican intermediaries.

After Libre Abordo agreed upon the transport of oil from Venezuela, it used a group of intermediaries to proceed with the resale of the barrels. It usually sought buyers from the same consortium involved in the scheme or refineries abroad. For example, a shipment delivered in Malaysia to a Chinese company was resold by Orin Energy, a holding company engaged in raw materials. Leal and Libre Abordo’s network had its main clients in Asia. In the corporate presentations, it is stated that two of the main buyers of Venezuelan oil were the Chinese companies PetroChina and Sinopec. Most of its shipments were also sent to Singapore and Malaysia, two major world refining centers.

In a first stage, Libre Abordo looked for clients and ways to place the oil in the global energy market. When the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned the Mexican company in June 2020, it indicated that the company used the same international routes, the same shipping processes and the same clients that two Swiss subsidiaries of the oil company Rosneft had used in the past. The Russian giant was one of PDVSA’s main partners, but left the business in February 2020 after being sanctioned by Washington for its dealings with Venezuela. Leal and his partners also consulted other participants in the scheme designed from the government of Maduro, like Alessandro Bazzoni, an Italian with a long history of business with PDVSA, and Philipp Apikian, a Swiss who has also been involved in the sale and shipment of Venezuelan oil. The White House sanctioned both in January 2021, as participants in the same scheme that has moved millions of barrels of Venezuelan crude oil under the radar of the U.S. sanctions.

One of the central intermediaries that Leal used to resell the crude oil was Elemento, a company incorporated by Bazzoni in Malta, in March 2015, with subsidiaries in the Caribbean island of Curacao and the United Kingdom, and which had previously traded Venezuelan oil in association with an American company. Elemento moved at least thirteen PDVSA cargoes between February and December 2019. Following the dealings with Leal, Bazzoni’s company took over one of the first two cargoes that Libre Abordo took out of Venezuela. The merchandise resold by Elemento was delivered in Singapore to a Macao company ―a former Portuguese enclave in China, with a sovereignty status similar to Hong Kong until 2049 ― in April 2020, almost a year after it sailed from the Caribbean country.

It was not the first time that Elemento helped the Maduro government to take hundreds of millions of barrels of oil off the coast of the South American country, according to the thousands of documents in the hands of the two media that are part of this investigation. To resell the shipments, Elemento used Swissoil Trading S.A., an energy company founded in Switzerland in 1998, which has acted as a reseller of raw materials in the Middle East and Asia, with Apikian as the sole administrator. With the intention of replicating this scheme devised by Elemento and reducing the losses and legal issues of resorting to other intermediaries to resell crude, on February 11, 2020, Leal founded Cosmo Resources in Singapore. The aim, according to an organizational chart designed by Leal himself, was to share the company’s board of directors with his partner Bazzoni to continue marketing oil in Asia and other parts of the world.

Through company Cosmo, the Mexican businessman explored the idea of absorbing Libre Abordo and its subsidiary Schlager Business Group, in charge of giving administrative support to the operations of its parent company. On February 16, 2020, Leal sent an email indicating that he was considering the possibility of Cosmo buying Libre Abordo. A day later, Hugo Villaseñor, Cosmo’s CFO and a close friend of Leal, coordinated the opening of a bank account for the company. In an email sent to an executive of Alpha FX, a London-based bank specializing in foreign exchange and offering its services internationally for “companies and institutions affected by currency liability,” Villaseñor requested the opening of the account, estimating a monthly flow of money ranging from 15 to 50 million euros. The account was opened on the recommendation of Richard Rothenberg, CFO of Elemento.

Cosmo’s role is crucial to understanding how the oil trades were capitalized under the guise of humanitarian aid. In the application to open the account, the company explained that its main source of income came from payments made by PetroChina and Sinopec refineries for oil shipments from Venezuela. Other income came from payments made by other commodities intermediaries, such as Beaconsfield Commodities Trading, a Bazzoni consortium incorporated in Switzerland, with subsidiaries in the Cayman Islands, South Africa, Switzerland and Sweden., On the other hand, the main cash outflows of Cosmo were payments made to Elemento and Libre Abordo, which were in charge of taking the oil out of Venezuela. One of the plans of the young Mexican businessman was to do the same business he had done with PDVSA and other Latin American oil companies, like Pemex, Colombia’s Ecopetrol, and Petroecuador.

Rosneft’s exit from Venezuela propelled the business of Leal and his partners. With the departure of the Russian giant, one of PDVSA’s main partners, the quantities of crude oil to which the Mexican network had access skyrocketed. According to the Department of the Treasury, by April 2020, Mexican businessmen received around 40% of the Venezuelan oil company’s exports. But it is true that the more their businesses boomed, the more Leal became concerned about the legal status of the deals of his companies with Venezuela. In December 2019, he sought advice at the U.S. law firm, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP. In March 2020, when Leal was already under the scrutiny of the United States of America, a Mexican law firm also issued its legal opinion on the sanctions that Leal and Libre Abordo were likely to face.

From Mexico, Leal designed different schemes to do business with Venezuela, and used financial engineering to manage his assets in an attempt to erase the money trail. The documentation in the hands of EL PAÍS and Armando.info contains thousands of emails exchanged between the members of Leal’s plot: Spreadsheets with the value of crude oil and the monthly flows from marketing the shipments, as well as export contracts, invoices of purchase and sale operations and financial advisory services. There are also bank references, business plans considering the possibility of entering the copper and aluminum market, and a list of payments for general and administrative costs of the different companies in the network, i.e. rent, utilities and international travel expenses.

A document with the income of Leal’s companies recorded in 2019 shows the huge rise of this group of businessmen, virtually unknown until then. That year alone, five companies linked to the young businessman collected over $107 million, even though they had not yet reached the peak of the business with Venezuelan oil. The highest payroll payments in these companies were the salaries of Leal, 750,000 Mexican pesos a month (just over 37,000 dollars), and his mother and sister who were paid half a million pesos (25,000 dollars). The file with the 2019 accounting, also includes the salary of the grandmother, who that year earned 30,000 Mexican pesos a month (1,500 dollars).

EL PAÍS and Armando.info have been able to verify that Leal and his entourage used at least 50 companies to hide the money trail. Behind each business plan, there was a company to carry out his projects. In most cases, Leal did not appear as a partner, but as a legal representative. Veronica Esparza and her daughter Olga Maria Zepeda Esparza, or other family members, were usually behind the companies. In his broad portfolio, he also created structures in tax havens, where the identity of the partners does not openly appear in the records and where it is easy to hide high flows of money, thus evading tax payments. One of the companies is JLJ Technologies LLC, incorporated in Wyoming, ―a state of the Union that in practice serves as a tax haven―on March 20, 2019, where Leal was registered as the sole administrator. This company had no real business operation, but allowed Leal to hide the trail of the partners behind his companies.

He also created Mystic Universe, a company in the British Virgin Islands, ―the largest tax haven on the planet in terms of turnover and number of incorporated companies― which had a mirror company in Ontario, Canada. Both companies were incorporated by Leal in May 2019, in the course of his first trips to Caracas. According to the articles of incorporation reviewed, Leal owned 90% of the shares, while his mother, María Teresa Alfaro, and his sister, Carlota Jiménez, owned 5% each. On August 5, 2019, Mystic began operations as a holding-operating company that absorbed control of other companies linked to Leal.

One of the presentations prepared by Leal’s team assures that Mystic invested in companies engaged in technology, energy and commodities in America and other countries outside the continent. “Mystic Universe’s goal is to change the world; hence, we focus on core industries ⸺energy, technology, commodities, finance and healthcare,” is a statement that stands out in the document. On its former website, Mystic claimed to have invested more than $300 million. But all the beneficiaries of Mystic’s investments were other companies of Leal.

Mystic was presented in the Mexican media as a Canadian investment fund focused on social impact projects. In media pieces published between August and September 2019, it was announced that the company would invest in Hábitos Luzy, the Mexican subsidiary of Luzy Technologies, a company that has been blacklisted by the U.S. Department of the Treasury since June 2020. On paper, the company specializes in providing health and food advice through a mobile app, managing industrial canteens and reselling sanitary products.

Leal, who constantly devised how to reorganize his vast portfolio of companies through trusts, front companies and front men, approached Morgan Stanley investment banking on April 16, 2020, to assess the option of Mystic Universe being listed. Mystic’s CFO was José Luis Chávez Calva, who was a general coordinator at the state-owned Energy Regulatory Commission (September 2016 to June 2017). He was one of the two persons considered to lead the Federal Electricity Commission, the main government company in the sector. The politician, Manuel Bartlett, was finally appointed the position.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.

They lose their freedom as soon as they set foot on any Trinidadian beach, and their “original sin” is an alleged debt that these women can only pay by becoming sexual merchandise. They are tamed through a prior process of torture, rotation and terror, until they lose the urge to escape. The growth of these human trafficking networks is so evident that regional and parliamentary reports admit that the complicity of the island’s justice system in this machinery of deceit and violence multiplies the number of victims.