One hand of the government of Nicolás Maduro does not even know what the other hand does in Western Sahara, the former Spanish colony that Morocco illegally annexed itself in 1975. While the Chavismo pledges solidarity to the Saharawi pro-independence movement of the Polisario Front, the Venezuelan state's petrochemical companies continue to buy from the invader valuable phosphate cargoes extracted from mines in the occupied territories.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

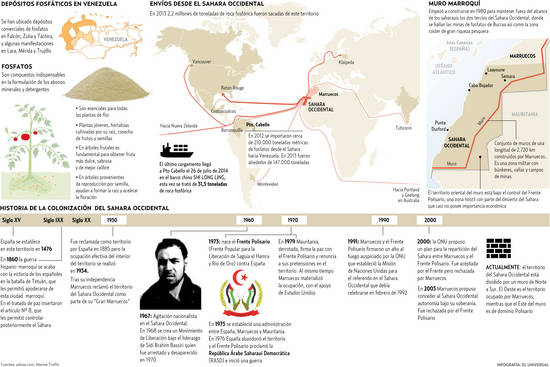

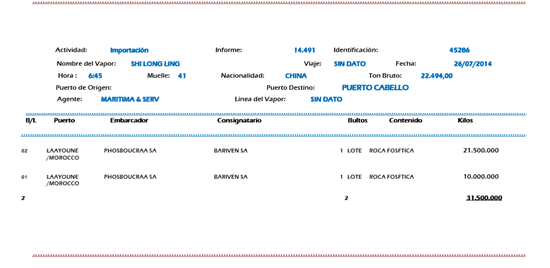

In Puerto Cabello, state of Carabobo, 31,500 tons of phosphate have just arrived aboard the Chinese flag steamship Shi Long Ling. The cargo came from Northwest Africa and was destined to Bariven, a subsidiary of the Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA. The ship docked on July 26 after a voyage of more than 3,200 nautical miles, which would not be more than one of the many traces that are drawn and blurred on the map of the world's maritime traffic, were it not for the fact that the Venezuelan Government denounces the invasion that has existed for almost four decades in Western Sahara, the source of the cargo, while buying from Morocco, the occupying power, the phosphate that imports from that territory.

The political alliance with Saharawi nationalism does not go beyond words and other gestures, such as the construction of a school in this desert territory rich in phosphates, which until 1975 was a Spanish colony. "Greetings to the Polisario Front delegation!" said President Nicolás Maduro during the inaugural session of the III Congress of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), in the Ríos Reina hall of the Teresa Carreño Theater on July 26th. Two men - the ambassador of the Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR) in Caracas, Mohamed Salem Daha, and his advisory minister, Hadi Laroussi - stood up from the audience and bowed in return. Then, the official speaker of the event read a brief document of the pro-independence movement in salutation to the Chavismo's event. "The Saharawi are brothers of Venezuela and we bring the gratitude of the Saharawi civil resistance in the occupied areas of our country, which suffer the excesses and abuses of the Moroccan occupiers in a daily basis", the text said.

Almost at the same moment, the Chinese vessel Shi Long Ling reached the main port of Venezuela. Saharawi phosphate, essential for the agrochemical industry, is being imported regularly by companies of the Venezuelan State, which pays for it to Moroccan suppliers.

The last ship arrived two weeks ago, but this is not an isolated case. Marine Traffic, ExactEarth and other databases of maritime transit around the world place Venezuela among the destinations of vessels departing from Laayoune, the capital of Western Sahara, controlled by Morocco -the occupant- and from whose port bulk carriers loaded with phosphate ship.

On August 1st 2012, 22,000 tons of phosphate rock from Western Sahara were unloaded in Venezuela; on November 9 of that same year another shipment of 24,200 tons was received and last year 59,560 tons came in, on two ships that arrived on January 17 and then on May 12, 2013 in the docks that the National Armed Forces reserve in Puerto Cabello, through the Coordinating Office of Maritime Support of the Navy (Ocamar).

The bill of landings states that Pequiven, Bariven and other companies of the petrochemical consortium of the state import phosphate from Western Sahara. Thus it is reflected in the port registers with place of origin in "Laayoune, Morocco", despite the fact that the United Nations (UN) has been condemning in various declarations the extraction of natural resources from this territory, and that the national government stands for the independence of Western Sahara. So much that President Hugo Chávez always declared himself defender of the Saharawi cause.

In silence, far from the news outbreaks in Gaza, Syria or Ukraine, a war of varying intensity has been waged in Western Sahara for almost 40 years. When Spain left that colony in 1975, neighboring Morocco annexed the territory, which it claimed as a province of the former Great Morocco. Their expansionist ambitions overshadowed the desire for freedom and self-determination of the native population, the Saharawi people. The so-called Frente Polisario (acronym in Spanish of Popular Liberation of Saguía el Hamra and Río de Oro) took up arms against the Moroccan occupier, to whom neither the United Nations nor the international community has recognized any sovereignty over Western Sahara.

The UN has repeatedly condemned both the occupation and the extraction of resources from the Saharawi people in a series of resolutions and pronouncements. In 2002, the Corell Report - named by the then UN undersecretary general for Legal Affairs, Hans Corell - warned about the "exploitation and looting" of the territory.

At the heart of the conflict is the struggle for control of the rich phosphate deposits of the territory. The Spanish prospection made the first discoveries of the mineral in 1947. In 1963, the Bou Craa mine was developed, one of the largest in the world. Morocco is by itself, the largest exporter of phosphates on the planet. From their exports, estimates of El Economista calculate that about 1.75 billion dollars a year originate from deposits that are located in occupied Saharawi territory.

Also since 1975 the Saharawi struggle became a famous cause of the international left. There is no progressive event without a declaration, such as the recent PSUV Congress.

In 2004, Hugo Chávez himself received Mohamed Abdelaziz, president of the proclaimed Saharawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), and five years later, in 2009, he sent the ambassador of Venezuela in Algeria, Hector Michel Mujica, to fulfill the formalities of presenting his credentials in the Saharawi refugee camps that remain in Tindouf and other areas of southwestern Algeria.

Mujica reiterated Venezuela's support "to the right of self-determination of the Saharawi people and the constitution of an independent state", which a week later triggered the closure of the Moroccan embassy in Caracas.

Like China with Tibet or Taiwan, or, at the time, Indonesia with East Timor, the Kingdom of Morocco does not recognize the Polisario or any other group as representative of the Saharawi people, and sees with apprehension any nation that does so.

Morocco lamented that Venezuela did not take a more neutral stance on the matter of the Sahara and accused it of hostility. "The Caracas authorities have actively participated in the belligerent campaigns of the adversaries of the national unity and have compromised, in that absurd escalation, the highest Venezuelan spheres", concluded the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of that country in a statement released by the official MAP agency on January 15, 2009, the date on which it closed its representation in Caracas and moved it to the Dominican Republic.

"The opening and presence of a representation in a country reflects the will to strengthen relations with that country in different areas, but this presence is useless when major considerations hinder the development of those relations", the Moroccan Foreign Ministry added.

Chávez did not speak on the matter, nor did the now President Nicolás Maduro, who then served as chancellor. Reinaldo Bolívar, vice-minister of foreign affairs for Africa, was in charge of the reply. He expressed surprise because, according to his testimony, he had not received any call to anticipate any inconvenience in Rabat. While noting that the kingdom of Morocco had the right to shut down its embassies anywhere in the world, he judged "the Moroccan speculations as tendentious and disrespectful, about Venezuela financing and participating in war campaigns against that country".

There

was no more of that impasse. But even in the midst of the dispute, and

even later, several ships left their wake in the Atlantic while transporting

phosphate expelled from Western Sahara to the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela,

the spirited ally of the Saharawi insurgency.

The Saharawi ambassador in

Caracas, Mohamed Salem Daha, warns that "any exploitation of the resources of

the Sahara without the authorization of the Saharawi is illegal". He is unaware

of phosphate imports for this part of the Caribbean. He assures that he has

never heard about the subject but does not fail to point out, if that were the

case, that those who trade in phosphate, fishing, oil and sand extracted from

Western Sahara fuel an endless conflict with disappeared persons, antipersonnel

mines and the construction of a 2,700-kilometer wall that divided the

population.

However, Daha highlights the support Venezuela has given to the Saharawi liberation since 1982, when Caracas recognized the SADR as a sovereign country. The Bolivarian diplomacy has gone further: on September 17, 2011 inaugurated, in partnership with Cuba, the Simón Bolívar School for more than 350 students of 4 wilayas, as they know the refugee settlements that were established in a region of Algeria.

That of Western Sahara is a forgotten conflict, not longer quite bloody but with complex implications. The internationalist Julio César Pineda, who approached the case when he served as Venezuela's ambassador to Libya, believes that Maduro's government should be prudent. "The issue is delicate in the commercial scope because it is a strategic mineral, but in the diplomatic sphere it is regrettable that Venezuela has broken the balance that it had always maintained and that ended with the closure of the Moroccan embassy".

For Pineda, the conflict has been prolonged in a kind of cold war between Morocco and Algeria, around which the Diaspora of the Saharawi people has taken place. Not counting the dispersed population in exile, the Saharawi total more than half a million people spread across the occupied territories and a series of camps located in almost unknown areas of the Sahara desert.

The

quality of Saharawi phosphatic rock is recognized all over the world. It is "a

yellow to light brownish-colored mineral with scarce fossils - some remains of

fish and coprolites - and without organic matter, consolidated only by a

clayey-loamy cement that allows its disintegration with ease and, consequently,

its subsequent treatment", describes the

magazine of Industrial Technique of Spain in its edition of June,

2004.

Despite the international provisions calling into question the

extraction and commercialization of products from Western Sahara under Moroccan

control, the Moroccan government company "Office

Cherifien des Phosphates (OCP)

" exploits the phosphate mine in Bou Craa, occupied territory, through its

subsidiary Phosphates de Boucraa S.A. (Phosboucraa).

Morocco is one

of the main exporters of the mineral, which arrives in Puerto Cabello through

its state-owned companies Phosboucraa and OCP, as can be read in the reports of

the Puerto Cabello Chamber of Commerce. At least five ships, between 2012 and

July 2014, have unloaded 137,260 tons for Venezuelan state-owned companies

Pequiven and Bariven - the latter, in charge of Pdvsa's international

acquisitions. In the rest of the world, Saharawi phosphate customers are usually

private companies. In Venezuela, Pequiven and some of its subsidiaries, such as

Tripoliven, process Saharawi phosphate in their plants for the production of

different chemical products, such as fertilizers and detergents.

The

country imports phosphate from Africa because it does not exploit most of the

mines it has in the states Falcón and Táchira. "Venezuela, despite possessing

deposits that could cover the national demand, has the need to import phosphatic

rocks, with the consequent loss of foreign currency", explains the geologist

Francisco Raúl García. "If the known deposits of phosphatic rocks are put into

production, we could shortly cover the national demand and even export surpluses

to neighboring countries".

Tripoliven, which has among its shareholders

Pequiven, Valquímica and the Spanish private company FMC Foret, admits that it

purchases the mineral from Western Sahara to Morocco. Nicolás Marín, president

of its board of directors, maintains that it is a transparent operation. "The

rock that is more in line with the requirements of Tripoliven is that of Bou

Craa, imported from Morocco", he explains. The Saharawi mine, according to

figures from the OCP, on average produces and exports between 2.3 and 2.5

million tons per year, a little less than ten percent of the whole Moroccan

phosphate production. Marín notes that the projects for the exploitation of

phosphate "made in Venezuela” are under development: "Logically, when the

product is available on the market, we will look for it here".

The Spanish company FMC Foret, one of Tripoliven's shareholders, was criticized in the past for purchasing phosphatic rock from Western Sahara to Morocco. A report from the Ethics Council of the government of Norway in 2010 he called attention to this firm, which recognized without embarrassment the purchase of the mineral and its willingness to maintain imports from Layounne, on the understanding that, in its opinion, Morocco was legally and de facto the administrator of the territory: "The company's plant in Huelva, Spain, is heavily dependent on access to the quality phosphate found in Bou Craa".

But the Huelva plant closed in 2010. FMC Foret reported that the closure had nothing to do with the exports from Western Sahara, which, in any case and since then, were stopped.

Regarding its investments in Venezuela, where Saharawi phosphate shipments continue to arrive, the Spanish FMC Foret indicated, in a report delivered to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC, the U.S. stock-exchange supervisor), that it maintains an uncontrolled investment in Tripoliven's business valued at nine million dollars by September 30, 2012.

According to the Council of Ethics of the Norwegian government, "Morocco's exploitation of the phosphate resources of Western Sahara constitutes a major violation of the rules. This is not only due to the fact that the local population is not receiving the benefits; but the current form of exploitation also contributes to maintaining an unresolved situation and, consequently, the presence of Morocco in a territory over which it does not have sovereignty".

Tripoliven

was created in 1972 and began operations in 1977. Since then, according to

Nicolás Marín, president of the board of directors, the company buys phosphate

rock from Morocco for its production. For Marín, the resolutions of the United

Nations (UN) are a matter of another level that would not correspond to his

company to define.

"These issues are unrelated to the normal

operation of Tripoliven. I don't know how it's being handled, but we prefer to

stay out of that", he says. In the meantime, no government agency has shed

any light on the matter: Pequiven and Bariven, both state companies, did not

respond to the request for an interview to address this issue until the date of

this publication.

Tripoliven processes around 100,000 tons of phosphatic rock in Venezuela every year, most of which is bought from Morocco - including that of Saharawi origin - and its products serve as supplies for the country's detergent industry.

Marín notes that they have never received a complaint from the UN, but remembers that they were once contacted by a non-governmental organization. It was Western Sahara Resource Watch (WSRW) which, from its headquarters in Norway, points out that the response offered did not mention Western Sahara: "Regarding your request for information, we comply in informing you that Tripoliven is not importing rock from the company OCP. FMC Foret is one of Tripoliven's partners, holding 33.33% of the total shares", informed the Venezuelan company to its Norwegian interlocutors.

The organization, with representation in 38 countries, defends the preservation of the resources of the occupied territory for the use of the Saharawi people. "Half of the population of Western Sahara has fled the territory following the brutal Moroccan occupation", says Erik Hagen, president of WSRW. "They live in deep poverty in refugee camps and do not earn a single penny from this trade. The income that Moroccans obtain from it is used to finance and entrench the costly occupation".

The

phosphate from Western Sahara also arrives in Colombian port, but under the name

of a company with state capital from Venezuela. It is "Monómeros",

"the only subsidiary company in which Pequiven participates, with headquarters

outside the Venezuelan territory, created to promote basic and intermediate

chemical products to the manufacturing industry and fertilizers for

agriculture", according to Pequiven on its website.

In Barranquilla

- the Colombian Atlantic port to which the cargo is destined - is its main

headquarters. Last year, at least five ships arrived with 107,000 tons of

phosphate purchased from Morocco worth approximately 17 million dollars,

according to a report by the WSRW organization.

In previous years,

shipments of phosphatic rock had already arrived at the port of Barranquilla,

sometimes making a stop in Puerto Cabello. The vessel DD Vigor, for

example, made a stop in the Venezuelan port before unloading on July 23, 2008 in

Colombia nearly 15,000 tons of phosphate from Layounne. Like this case, at least

five other ships did the same during that year.

Of the countries that

recognize the Saharawi Republic, several have established, as part of their

support, the prohibition to import products from the occupied territory. In

Latin America, Argentina, Brazil and Chile, have not pronounced themselves in

favor of the Saharawi cause. It is not surprising, therefore, that it is

precisely in two of these countries (Argentina and Brazil), where the Moroccan

OCP maintains offices in the region.

For Hagen, president of Western

Sahara Resource Watch, stopping this commercial exchange of Saharawi phosphate

between Morocco and Venezuela would be the best sign of support from Caracas.

And perhaps, of consistency.

"The Venezuelan government has had excellent

words of solidarity for the oppressed people of Western Sahara. For that reason,

it is sad to see that it is the only government in the world whose state

companies are involved in these imports", he declares. "To end this trade would

be the best example of solidarity, and support for international legislation,

that could be done".

This article is the product of a team effort published simultaneously by El Universal and the investigative journalism website www.armando.info

Since its opening in 2017, the Porsche Design Tower quickly became a symbol of luxury and ostentation in South Florida. Magnates from all over the world retreat behind the discretion of its tinted glass windows and virtually anonymous legal entities. But in recent days, two police investigations into illegal financial flows from abroad placed the building under an inconvenient spotlight. The justice just seized an apartment of over five million dollars from a Venezuelan agent.

As if they were pieces of a broken mirror scattered in many islands around the world, several offshore companies form an oil-trading business network that reveals the trajectory of Alessandro Bazzoni and Francisco D'Agostino. Both of them, together with the Venezuelan telecommunications magnate Oswaldo Cisneros, landed in 2016 in the Orinoco Belt to fill the vacancy of the original partner, Harvest Natural Resources.

Aside from ethical questions, the logic of a private entity opening an offshore company seems elementary —to declare its profits in a territory where it can pay less tax than it should in its place of origin. But when it comes to a state-owned company like Petróleos de Venezuela, which is not obliged to pay taxes - and therefore does not need to evade them - it is difficult to understand why within its business scheme there is contracting with companies established in tax havens and there is even the creation of their own subsidiaries in these places. What does the Venezuelan public treasury gain from this?

The member of the US Cabinet, Wilbur Ross, is one of the owners of a company that provides maritime transport services to Pdvsa, a client that in 2015 contributed over 11 percent of the profits to his shipping company. Although the official had to get rid of his mercantile properties to hold his position, he kept a participation in that line of business through a complex offshore structure in the Cayman Islands. Thus, he did not only do business with chavista Venezuela, but also with an associate of Russian President Vladimir Putin. Both countries are subject to economic sanctions by Washington.

The name of the former head of the Venezuelan oil company in Colombia appears in the papers of Mossack Fonseca with 100% of the shares of a company created in June 2011, of which she requested to be dissolved six months later. She is unemployed since August 2015, when she was replaced by the ex-sister-in-law of President Nicolás Maduro

The former Vice President of Finance and director of the state oil company was one of the executives in the industry with more charges and accusations. In 2006, the Office of the Comptroller opened a proceeding against him for not filing the sworn statement of assets. In 2011, he became noticeable for his alleged participation in the Ponzi scheme of Francisco Illaramendi. In 2009, four years after having him as a client, Mossack Fonseca learned that he was a Politically Exposed Person, but maintained the business relationship because no "links to illegal activities" were found.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.