They lose their freedom as soon as they set foot on any Trinidadian beach, and their “original sin” is an alleged debt that these women can only pay by becoming sexual merchandise. They are tamed through a prior process of torture, rotation and terror, until they lose the urge to escape. The growth of these human trafficking networks is so evident that regional and parliamentary reports admit that the complicity of the island’s justice system in this machinery of deceit and violence multiplies the number of victims.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Lilia* never imagined that a simple friend request on Facebook could be the beginning of a nightmare. The person who contacted her could not be less suspicious ?a teenager, like her, who also lived in Maturin, in eastern Venezuela. At first, they became friends on the social network and then began to meet at the high school where Lilia was studying. She invited Lilia to parties and other social venues with her friends. One day, four months after the beginning of that virtual friendship, she offered her a job “picking up bottles in a restaurant” to earn “good money,” an irresistible bait for Lilia - 17 years old at the time - in the midst of the Venezuelan crisis.

But that offer was as far from reality as it was from Venezuela. Deceived, Lilia ended up as a hostage of a sexual exploitation network in Trinidad and Tobago. Like her, over 21,000 Venezuelan women, both adults and minors, have been victims of human trafficking in the last six years in that country, as per official figures from the Caribbean Community (Caricom). The victims, according to a Caricom report, are usually between 18 and 25 years old, although a significant number are between 16 and 17, and some, even younger.

Once recruited by criminal gangs?often through deceit to get them to accept their transfer to the island?, they are then subjected to conditions of slavery through physical and psychological violence. This journey of horror leads the victims to prolonged sexual exploitation, which can result in arrest, a dangerous escape, or death. Meanwhile, the human trafficking business between both countries remains profitable and the criminals go unpunished.

Deceptive job offers are often one of the most common recruitment strategies that these criminal gangs use, a fail-safe bait in a country with 94 percent poverty, according to a 2020 survey by Universidad Catolica Andres Bello. The financial situation incited an unprecedented 18 percent migration of the population ?a total of 5.5 million Venezuelans in the last six years, based on data from the United Nations Refugee Organization.

Lilia told her parents that she was going to a party at a friend’s home. That night, in early November 2019, the teenager left with a small purse only. Her departure did not raise any suspicion in Jorge,* her father, but worries began when she had not returned home a few hours later.

The following days, she sent messages to her closest on Facebook, which intended to be reassuring, “with very vague information, no word about where she was or who she was with,” affirms Jorge. It seemed that she was in Colombia or on her way there, but she did not give any information that allowed to locate her. Then, three weeks later, her father received a phone call that confirmed his worst fears ?his daughter had been arrested in a police raid in Cunupia, in Trinidad and Tobago, along with dozens of teenage girls, who were to be sexually exploited.

About 50 trafficked women were locked up in different rooms, in a bar in the Chaguanas region and in a house located in the Diego Martin sector, in the northeast of the island, according to media reports. These places were a sort of “collection centers,” from where the women were to be distributed in many nightclubs on the island, as the reports said. Like Lilia, there were other Venezuelan teenagers from El Furrial - another town in the State of Monagas - and from Maracay, State of Aragua.

Facebook chats, which her father could check later on, show that her recruiter convinced Lilia for months to undertake the trip. The Facebook profile of this trafficking networks’ recruiter shows a very young girl with a network of more than 2,600 friends. This list includes hundreds of names of teenagers, mainly students from different high schools and universities located in Maturin, but also from different cities in the eastern part of the country.

“Maybe we, as parents, should take more precautions,” Jorge questions himself. “I always had so much fear and talked to her a lot to protect her, but my daughter had to learn it in the worst way. Financial conditions make people desperate and then come these type of individuals to offer quick solutions,” he complains.

A misleading job offer was the same bait that recruited Zurima,* 29, a resident of Petare, Caracas. She and another woman were recruited in 2019 by a man named Jonathan. Zurima held at that time a position as a telephone sales executive for a courier company, but her salary ?back then the minimum wage in Venezuela was equal to less than $6? was insufficient to cover her expenses, especially those of her father, who was ill and lived in the State of Sucre.

“I used to send medicines to my dad, but I couldn’t manage it all. We had our friend Jonathan, who told us that he was doing well in construction there, in Trinidad and Tobago. I even knew his family, his girlfriend. He always told us that there were job opportunities cleaning houses, or in bars or restaurants. Until he told us about the opportunity to take care of the mother of a Trinidadian, who, according to him, was a serious man,” recalls Zurima.

To travel to Trinidad, they had to go to Güiria, also in the east of the country, from where they would take a boat to the island. The price of the ticket was US$ 500 for both friends, but they managed to raise the half only. The rest was to be covered by their employer, as they agreed with the man in charge of the boat that would disembark on the island. But once they arrived at their destination, their supposed employer announced that he would not pay the full amount, so the captains withheld their passports, which they never got back. They had already become - without even suspecting it - hostages of a human trafficking gang.

Until a few years ago, Venezuelan trafficking victims, on a smaller scale, used to leave the country on commercial flights to Trinidad. But in recent years, the States of Sucre and Delta Amacuro have become the hot spots from which peñeros (small fishing boats) constantly depart for the island, a situation that has not stopped despite travel restrictions imposed during the covid-19 pandemic.

A friend who lived in Güiria convinced Maritza* to make the trip to Trinidad and Tobago with the promise that she would get a job as a waitress. Born in Irapa, State of Sucre, she recalls that this person assured her that her pay would be “decent” and that they would even give her a place to live. He tried to persuade her to get three other girls to travel with her, but she could not convince others.

Irapa and Güiria, two towns in the State of Sucre, in eastern Venezuela, are among the places that the Caricom report identifies as the most active in recruiting victims for trafficking networks. The document puts the number of victims extracted from that area in the last six years for sexual exploitation in Trinidad at 4,000. However, the victims taken to these departure points are also recruited in different Venezuelan cities, including Caracas, La Guaira, San Cristobal, Maracay, Maturin, Valencia and Puerto Ordaz.

Survivors of human trafficking report that they had to go through at least three stages within the Venezuelan territory before being embarked. In each of these stages, those involved play a specific role, not necessarily connected to the next links. Once they have been recruited by a friend or acquaintance for the criminal organizations, the victims fall into the hands of groups that will take them to the points where they will be held for several days, waiting to board the transport that will take them to their destination.

Maritza set out on April 14, 2019, from her village to Güiria, a coastal journey that takes about 50 minutes by car. She, who was then 17 years old, had had to wait a month while her recruiter rounded up his other victims. When she arrived, her friend took her directly to Las Salinas, another coastal sector of the State of Sucre, which has become one of the clandestine and early morning departure points.

Before boarding the boat, Maritza was taken to a house with open spaces and a patio with banana trees, where she met 20 other women, five men and the captain. They all waited under the shade of the tropical fruit tree until nightfall. But that day, they did not leave. A boy arrived in the early hours of the morning to warn that the Trinidad Coast Guard was keeping “heavy” watch in the area.

Other obstacles would appear on the way, or rather, in the middle of the sea. The boat left Las Salinas at midnight and, shortly after leaving, the engine died. The captain returned to shore and Maritza specifies that the official time of their departure from Venezuela was at half past midnight and their arrival in Trinidad at six thirty in the morning.

Navigation between the Paria peninsula and Trinidad can be hostile and dangerous. Victims agree that traveling aboard these peñeros is a chilling experience. The fear of waves crashing against an overloaded boat is present throughout the journey. In fact, there is word that four boats have been wrecked in the last two years.

Even though this is a traditional trade route in the area, its use as a migration route has consistently grown along with the Venezuelan crisis, and has not stopped during the covid-19 pandemic, as it is estimated that one to two boats still depart every night, based on figures released in January by the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the United Nations Organization. All in all, this has occurred due to the corruption and blind eye of Venezuelan authorities, who are responsible for supervising the boats both in Tucupita and in Güiria, who fail to carry out the required migratory and port registrations, or charge fees for each irregular peñero leaving for Trinidad, according to testimonies of travelers and data from the OAS Working Group for Venezuelan immigrants and refugees, consulted for this investigation.

It was on that route between Paria and Trinidad that the boats named Jhonaily Jose and Ana Maria disappeared in April and May 2019, and so far, there is no information about 60 of their passengers, who are still missing. It was known that several of the teenage girls and women on those boats had been pre-sold to human trafficking gangs. In December 2020, the boats named Mi refugio and Mi recuerdo, which also departed from Güiria, were shipwrecked ?33 people drowned in a murky incident.

The peñeros usually arrive in Trinidad in the middle of the night or at dawn, and as in Maritza’s case, in desolate clandestine ports, where groups of armed men wait for the travelers. The teenager arrived in one of these sites in Carenage, in the northwest of the island, an area where cases of human trafficking have been previously reported, according to Venezuelan immigrants in Trinidad and local media.

Testimonies from travelers indicate that armed men divide the disembarking migrants by sex, until those who “rescue” them show up. Some of these transporters may be local cab drivers or members of the gangs.

But the criminal organization that exists on clandestine beaches and in mountain areas also has tentacles in the island’s legal ports. In such cases, a new actor is added to the modus operandi that allows the triangulation between captains and armed groups ?the immigration police?, as some victims affirm and as confirmed by the Caricom research and reports from the U.S. State Department.

Zurima has witnessed that passports do not mean much in these offices. When they arrived in the port of Chaguaramas, the immigration officers did not stamp their passports and neither intervened when the captains of the peñero took their passports and left.

Even if the women enter with their documentation, many of them are not formally registered in the immigration forms. As it happened in Zurima’s case, officers may give the go-ahead or turn a blind eye to the gang leaders who pick up the girls in black vehicles, known as “maxi cabs,” and pay the boat captains. The Caricom investigation indicates that there are three modes of complicity: “those who are coerced or threatened into collaborating,” those who receive money to “turn a blind eye,” and those who actively participate in the criminal activities.

Once the victim disembarks, the trickery designed by these criminal networks to trap them dissolves. When they set foot on the beaches, they let them know that there is no turning back. That the job offer does not exist. What do exist are a debt and a contract that they never signed with the criminal gangs.

Fernanda*, 19, born in Tucupita, barely understood English when she arrived in Trinidad. Hence, when she disembarked at Playa Lucero, in the island’s southwest coast, she did not realize that her freedom had a price. “A Trinidadian man handed some money to the friend who brought us. I thought it was from previous passengers. The same man sat us down and asked if we wanted to take a bath. I still did not understand. And then, I saw my friend getting on the boat back to Venezuela,” she recalls.

Soon after, a woman arrived and took Fernanda to a nearby hotel. It was there that the procuress of this cell, a Venezuelan national, appeared. She told Fernanda that she had acquired a debt of US$ 1,500, and if she did not pay, she would be sold to another more dangerous gang, where she would be beaten, abused or killed.

The dreams of Fernanda, a teenager who worked in a family business until recently, shattered in an instant. She was in a hotel in Lucero Beach, Trinidad and Tobago, when she learned the news. Her captors informed her that she would be prostituted. The announcement came from the mouth of a man who said his name was Randel Jones and claimed to have “bought” her from the man who had taken Fernanda to the island. She was now to accompany him to Port of Spain.

The made-up debt that generates the trip to Trinidad is the original sin where the story of organized crime is born ?from that moment on, the women can only live to prostitute themselves and, thus, they are forced to pay it. The amount of money that Fernanda allegedly owed was the amount that she expected to save during the following months in some job that she may get as a saleswoman or waitress - as she believed - to help her family in Tucupita. The notice from her captor was a slap in the face to her self-esteem. “My freedom was worth US$ 1,500. Just remembering it makes me angry.”

Learning that she had been sold was just the gateway to horror. Fernanda had entered a “cooling off" period, a sort of preparation for her later sexual exploitation. Experts on how human trafficking gangs operate describe it as a moment in which criminals “break” the spirits of the victims, an intermission before taking them to sexual exploitation. The testimonies from eight women who survived human trafficking, as well as four relatives of the victims, who were interviewed for this Armando.Info and CONNECTAS investigation, give an insight into the scope of this nightmare.

It can take days or weeks. Women suffer intimidation, threats, harassment, sexual abuse and violence… a strategy to break their will to escape, seek help or report the criminals. Extortion does the trick. “They make you psychotic,” Fernanda recalls to describe the mental state in which she sunk, a mixture of terror, shame and despair.

After more than 10 hours waiting at the port of Chaguaramas, Zurima and her friend were picked up by their alleged employer. He immediately ordered them into his car. “We didn’t understand English, just the basics. We wanted to go back to Venezuela, but we had no money, so we got in the car, scared,” she recounts.

As part of the strategy to “break” them, they rotated the following days between two houses. On their first night in Trinidad, at three in the morning, two men burst into their room. Zurima remembers that they were high. They made advances and there were tense moments, but in the end, they left. “We got out of that. I thought we had survived the worst night,” she affirms.

But she was about to find out that the worst was yet to come. A few days later they were moved, along with three other Venezuelan women, to a house in the Diego Martin area, west of the capital. There was a man called “boss” with other members of his gang. They were all doing drugs and drinking.

She and her friend were sent to a room with no doors and no furniture. There was only a mattress on the floor, where two other Venezuelan women were. At eleven o’clock at night, the boss said to Zurima’s friend, “You go to the room with him.” They cried their goodbyes. They did not know if it would be the last time they would see each other. “Let’s forget about your children, your family,” Zurima said to her friend before the man grabbed her from behind. “We hugged for a few seconds, crying nonstop,” she describes.

A few minutes later the boss returned, yelled “trash” at the other two women and grabbed Zurima by the arm, who would not stop crying. “Don’t cry, don’t cry,” the man told her. “I was crying and shaking. I was speechless.” The man took her to the other room. He took off his clothes and cracked his knuckles as a sign for her to hurry. “No, please. I am not a prostitute,” she told him. The man grabbed her by force, pulled off her shirt and pushed her onto the mat that was on the floor.

"I was shaking my head no, crying. He took out a condom, put it on and lay on top of me. It was the worst. It was horrible. He covered my mouth and kept telling me not to cry,” she recalls.

Maritza and other Venezuelan women were intimidated for two days to explain them that their job was to prostitute themselves without expecting any money in return. The women tried to resist, which resulted in an atrocious punishment. They were transferred for a week to a wooden plank house in the mountains, where they were isolated, beaten and raped.

Once the gangs ensure through intimidation and violence the silence of those who will become victims of sexual exploitation, a profitable “business” begins for the criminals and hell for the women. After the initial tortures, the Venezuelan women rotate through different bars, brothels and hotels on the island. Fernanda’s destination was a “luxurious area” in Port of Spain; Maritza’s was a house on the main street of Diego Martin; and Zurima’s night of horror ended the next day in a police raid.

When she arrived at the bar known as Spanish Harlem or at other called Hawaii Bar, Fernanda says she worked until dawn, nonstop, until all the “customers” left. Deceived by the recruiters who sold them to criminal organizations, coerced through violence, without identity documents or regular immigration status, after days of “cooling off,” the Venezuelan women were finally subjected to sexual exploitation.

Fernanda was taken to the bars in black SUVs ?which have become the distinctive means to transport women for prostitution on the island? every night during the five months she was held in a house in El Socorro, escorted by one of the procuress, a Venezuelan woman. For the victims, the ordeal is not limited to the nights of sexual exploitation… it extends to the before and after that moment.

The women are forced under threat to take drugs. They are often isolated, cannot leave the houses where they remain under constant surveillance, have no access to the Internet or a telephone line. They are forced to prostitute themselves every day. “There are no days off,” one of the women remembers. On a single day, they are forced to have sex with at least five men, says Marlene,* from the State of Bolivar, who was prostituted at the age of 19, when she had just been awarded her associate degree.

The crime of human trafficking goes hand in hand with a high domestic demand for prostitution in Trinidad, says Canadian researcher Justin Pierre, who was responsible for Caricom’s report. He affirms that Trinidad concentrates more than 80% of the demand for sex trade and prostitution in the Caribbean, even though it is an illegal activity in the country. And he considers that the local consumption of prostitution “is higher than usual.”

As in Marlene’s case, not all victims are unaware that they are destined for prostitution in Trinidad when they make the journey. But their extreme vulnerability, due to the Venezuelan humanitarian emergency and the obstacles to emigrate legally, as well as the slave-like conditions they are subjected to, also turn term into human trafficking cases.

“Consent was irrelevant in cases of sexual exploitation, as it often involved abuse of power and vulnerability,” states a report by the Parliament of Trinidad and Tobago on human trafficking in that country, released in 2020. “Sexual exploitation could also include ‘debt bondage,’ where victims participate in wrongful acts due to the perception that they have no choice.”

In late 2018, financial needs forced Marlene to accept the offer of an acquaintance to travel to Trinidad to work as an “escort.” The salary she earned in Venezuela was “peanuts,” she says, and she had to help support a home where her mom and other relatives lived, including two young nieces. “The power outages back then burned out our refrigerator and TV,” she recalls. Then, one night, five criminals broke into her house.

Marlene was one of the women prostituted in the brothels run by Jinfu Zhu, a Chinese man, and Solieth Torres, a Venezuelan woman. The names of both were mentioned in the media in Trinidad because they were arrested in a raid of several houses and bars in February 2019, in which 19 Venezuelan teenage girls between the ages of 15 and 19 were rescued. The court charged them with 43 cases of sexual offenses, according to news reports released at that time.

The dismantling of Jinfu Zhu exposed some figures about the business. The cost of a “one-time” service was US$ 100, while one night was US$ 250, recalls Marlene. Half of that money was kept by the bosses and the other half allegedly belonged to the women, but they never received it. It went into a piggy bank with which they were supposed to be paid at the end of their captivity. In her case, Fernanda says that each “customer” paid US$ 300.

The accounts are recorded in a notebook kept by the traffickers. They write down the total amount of the alleged debt and the profits generated by the women each day. Should a woman be arrested, the bosses add to her debt the fines they must pay for the bail bonds. They also deduct sums for food and the rent of the rooms.

One indicator of the surge in human

trafficking on the island is the increase in financial irregularities linked to

this crime. Figures from the Financial Intelligence Unit of Trinidad and Tobago

indicate that in the last four years the crime of human trafficking has

mobilized at least US$ 2.2 million in the financial system of the country. In

2017, 11 transactions for a total of TT$ 9 million, equal

to

US$ 1.3 million, were identified as suspicious of being linked to this

organized crime.

In 2018, the same number of cases were identified through the tracking of irregular movements of TT$ 2 million, a total of US$ 294,000. The identified cases increased to 23 in 2019, which suspiciously moved a total of TT$ 1.9 million, about US$ 279,000. There were other 11 suspicious transactions identified in the 2020 latest report of FIU (Financial Intelligence Unit) equal to TT$ 2.6 million, approximately US$ 392,000. Further information on the characteristics of these transactions was requested to FIU, but no response was obtained.

These amounts are a glimpse of what the crime is generating. One of the researchers who participated in the preparation of the report for Caricom on women trafficking on the island, and who asked to keep her name confidential, explained that it is difficult to quantify the profits of the gangs, as well as the number of victims or those concerned, “but the amount of money involved makes it a highly profitable business, because the victims of trafficking can be sold over and over again.”

In the thick of this business, the violence exercised by “customers” and traffickers becomes part of the everyday life for Venezuelan women, who must survive in organized crime networks.

Reina*, 20 years old, was forced to get high and drunk every weekend in a house under construction in San Fernando, where she spent a little more than a month in sexual slavery with another young Venezuelan woman. She says, “A month, more or less” because while she was kidnapped, the days went by in a haze. She could hardly remember, as she was not allowed to be aware of herself.

She had accepted in 2018 the offer of an acquaintance to travel to Trinidad in the midst of a precarious financial situation that did not allow her to cover the expenses neither for her nor for her daughter, in Maturin, State of Monagas. The woman promised her that she would receive lodging and food until she could find a job to settle down and be able to pay. But the man who came to pick her up in a boat in La Barra, Delta Amacuro, a dangerous place known as a transport point in the human trafficking business, was a drug dealer.

He forced her to use drugs; otherwise, he threatened to send her to the police to be deported. Since she noted that he was a man with potential contacts in the police and a member of a criminal gang, she realized that there was very little within her reach to escape from that hell. She remembers having a gun pointed at her head the day she refused to drink alcohol, while at the same time, she was trying to prevent her “boss” from raping her.

One of the modus operandi of the gangs is to rotate the women from place to place, generally every three to five months. Among the names of the businesses that have been recognized as places where sexual exploitation occurs on the island are Copa Cabana, Villa Capri, 4Play Bar, and Tzar Night Club. With the restrictions because of the covid-19 pandemic, some of these places have temporarily closed their doors. However, the business has not stopped.

Survivors report that it has continued at private parties for which they are hired and in the rooms of hotels like Alicia’s Palace Hotel and Dads Dan. This last establishment was reported for cases of women trafficking at least six years ago, when the owner and his assistant were arrested for trafficking two Venezuelan women in 2015 and for having a place engaged in prostitution. An attempt was made to ask the administrators of the above bars and establishments about these facts, but they did not answer. In the case of Dads Dan hotel, they said that they cannot provide information because the case is still open in court.

Once the victims fall prey to human trafficking networks, they face a maze with no way out. Escape routes are almost nonexistent. Some are rescued in police raids, but are then imprisoned in detention centers under precarious conditions. Others take the risk of escaping. And in a few cases, the only hope left to the victims is to cling to the word of the “bosses” that they will be released once they settle their debt. That is why they keep thorough accounts of how much money they generate for each day of exploitation, in order to know when they will be free to leave.

Fernanda, after working for five months for the gang, learned that she had completed the amount they demanded as a quota. Her captors offered her to stay working as a prostitute, but she refused, acted quickly to leave and preferred to “move far away” to another city in Trinidad. However, she lives in fear.

She had to change jobs because a man showed up asking for her, saying that she owed him money. “I’m afraid. I’m very careful about taking a cab, a car, walking. At some point I could run into them and I don’t know how they might react,” says Fernanda.

As to the case of Marlene, the raid on the “Chinese houses” resulted in her leaving the human trafficking networks. She worked for a while in a casino in Trinidad until she had enough money to return to Venezuela. She never saw a penny of the US$ 9,500 she had been promised she would receive, with which she had planned to buy a house for her family.

The most far-off possibility of getting out of the sexual exploitation circuit is to escape, a decision that very few make because they know it could mean death. Maritza took the risk of running away from the second house of sexual exploitation where she was being held. One night, she managed to keep TT$ 100 from one of the “services.” At two o’clock in the morning, she took advantage of her boss being asleep and took his cell phone.

She jumped over the gate of the house and ran as fast as she could to Diego Martin’s stadium, where she saw a car pass by and flagged it down. The driver agreed to help her and took her to a fast food place in Port of Spain, where she was to meet some friends who she texted to come and pick her up. “From that moment on, I started from scratch. Those were dreadful moments. I even was on the verge of dying. I don’t wish this on any other girl.”

Once she paid off her “debt” and managed to leave the house where she was sexually exploited for over five months, Fernanda tried to report her case to the authorities. In June 2018, she went to the San Fernando Police and accused her captor.

“Everyone was speechless like a statue, as if I was speaking nonsense,” she says. The officers, she recalls, took some “very quick notes and never did anything else.” Her captor is still at large and, as far as she knows, the “business” remains operational, with at least seven women forced into prostitution.

Data show that the crime has enjoyed full impunity in Trinidad and Tobago for almost a decade. There have been no judicial sentences throughout this time. A parliamentary report released last year indicates that from 2016 to April 2020 Trinidad’s police services received 484 reports of sexual exploitation, 119 of which were officially confirmed victims. Fifty-seven persons have been charged and nine were brought into court for this crime during that time.

The research on women trafficking in Trinidad, conducted for Caricom, warns that “the lack of convictions and solved cases accentuates impunity, and in turn, the cycle of crime. The accused, after being released, reoffend because they know that there are low levels of prosecution, delays in trial process, lack of convictions and corruption in the different institutions, states the report.

In the document prepared by the parliament, the police argued that there are obstacles in detecting cases and insufficient evidence to secure charges. They mentioned, among others, the lack of CCTV images and the difficulty to have access to DNA tests in Trinidad due to their high cost. They also argued the unwillingness of witnesses to testify and affirmed that “the victims were reluctant to cooperate.”

But trafficking and sexual exploitation survivors constantly repeat that their cases are ignored by the police. Zurima says that after her captors were arrested in a raid, she went for four months to testify at police stations and in court. “When we arrived, they frowned,” she recalls. She believes it was because they did not speak English. “The treatment was blunt. When we had already made progress on the case, whoever was in charge took a vacation and passed it on to someone else.”

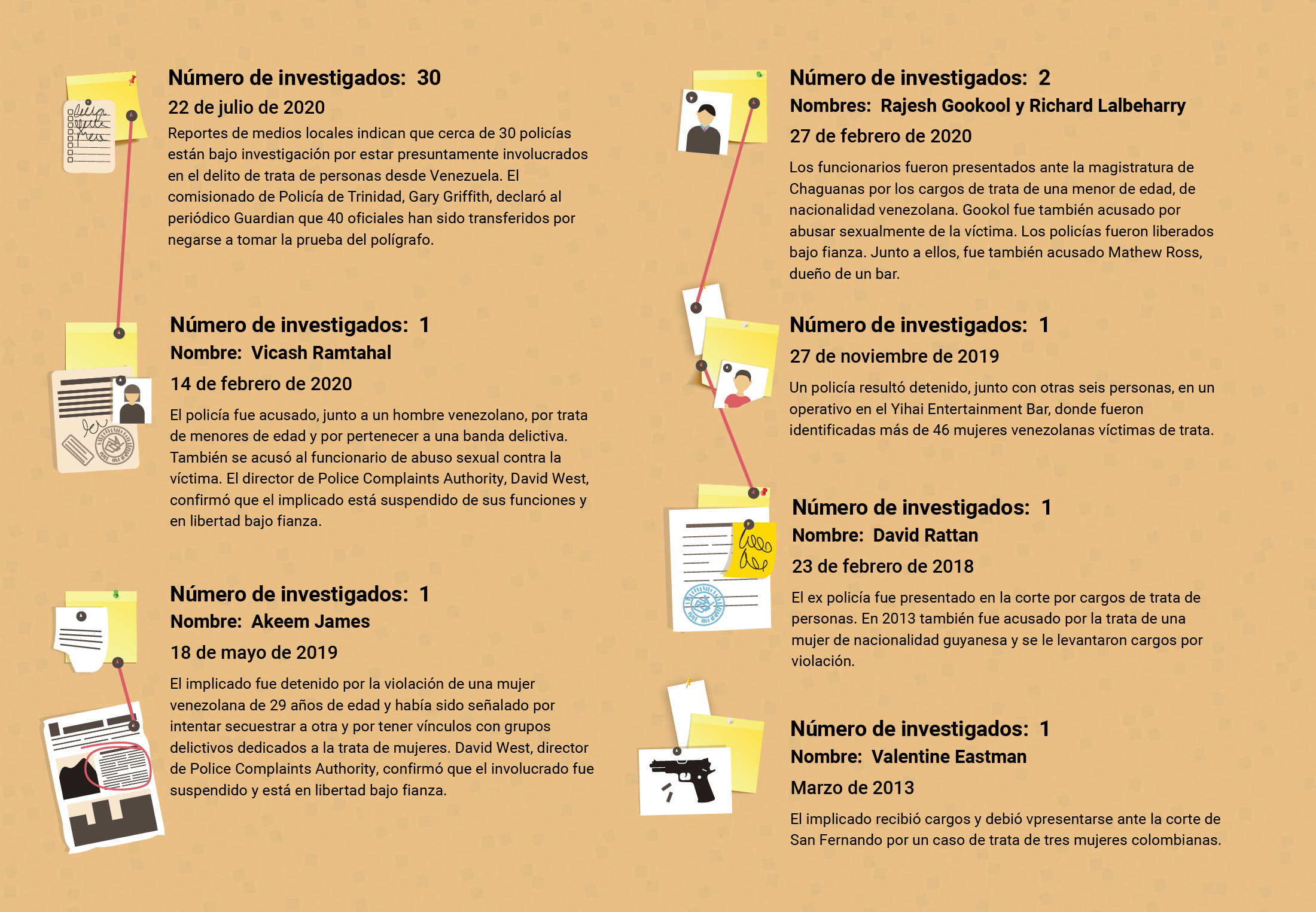

Police complicity is the elephant in the room when it comes to the lack of efficiency in the prosecution of women trafficking in Trinidad. Over the last three years, at least 36 police officers on the island have been associated to this crime - according to local media - but there have been no judicial sentences against any of them. Most of the victims in these cases are Venezuelan.

David West, director of the Police Complaints Authority, an independent organization that oversees police work in Trinidad and Tobago, says that in some cases, the officers involved take advantage of their position of authority to intimidate their victims and prevent them from reporting.

This was the case of two Venezuelan women who filed their complaint with this office but then disappeared, making it impossible to continue with the investigation, he says. “The women came and pointed out the officers who took advantage of them, but no charges were brought and the officers are still wearing their uniforms,” he points out.

Even the Ministry of Security agrees in the report made by the parliament that among the factors affecting the lack of sentences is “the public complicity of law enforcement and private sectors that participate in human trafficking and hamper the investigation.”

In August 2020 alone, 30 police officers were under investigation for involvement in a human trafficking ring operating between Venezuela and Trinidad and Tobago. Survivors interviewed for this investigation affirm that police officers are aware of the bars, houses and hotels where the crime is committed. “Some of them guard the house together with the gang,” says Maritza.

The research conducted for Caricom also indicates that police officers “provide transportation and work as security guards and even as pimps in establishments where prostitution and human trafficking occurs.” The report refers to cases where police have taken young women to a guesthouse elsewhere in Trinidad and charged people for “using” them.

Maritza witnessed this situation. She describes how the police would come to the house, where she was being held together with about 50 women, and select some of them to take them on a “date.” Fernanda also witnessed several times the visit of police officers at the place where she had to offer sexual services. “There was no problem with the police because he (her captor) befriends with all of them. The police are fully aware of what happens in those houses,” she says.

From time to time, there are police raids that intervene sexual exploitation centers, but this does not guarantee progress in fighting the crime. “In fact, some interviewees stated that high-profile raids may be exaggerated to make it look like the Government is doing something, but there are no real and serious procedures and protocols in place to address human trafficking,” Caricom’s research says about the cycle of impunity in Trinidad and Tobago.

One of such high-profile raids took place in November 2019, at the Yihai Entertainment Sports Bar in the Cunupia area, where 46 trafficked Venezuelan women were found. Among the detainees was a policeman. In February of the same year, as reviewed by local media, another officer had been arrested together with a Venezuelan man for being involved in trafficking of minor girls.

This journalistic team requested the Trinidad Police to give information about these cases and, so far, no response has been obtained.

The lack of prosecution of the cases fuels the victims’ fear of meeting again with those who sexually exploited them. In fact, some have been threatened by their captors from prison. Zurima says that the criminals she had reported contacted her on Facebook or called her on the phone. They told her and other informers that they would kill them if they continued with the accusations.

Eventually, she was forced to drop the case. “We had no protection whatsoever. We feared that if we ruin those men, they would follow through with their threats. They have a lot of money and weapons. We had no protection from the police. We told them about the threats and they warn us to make the right decision, because otherwise the men would be out on bail,” Zurima says.

The report prepared by the Parliament points out that the slowness of the judicial procedures conspires against the possibility of imprisoning the culprits. The victims “are not willing to wait years for trials to be initiated and completed.”

The vulnerability of Venezuelan immigrants, who risk deportation if arrested, also favors human traffickers. In the last two years, U.S. State Department reports have emphasized that the government of Trinidad and Tobago does not effectively screen illegal immigrants or refugees, as it does not establish whether they have been victims of human trafficking and if they require special protection before arresting them.

This particularly affects the Venezuelan population that has massively migrated to the island in recent years. At this time, according to figures from the Organization of American States, there are 40,000 Venezuelans on the island, but only 16,000 have a regular migratory status.

Activists, survivors and reports, like Caricom’s, agree that trafficking victims have been imprisoned for up to three to five years on irregular immigration charges, after they are accused of being illegally in the country or on criminal charges, such as drug or weapon possession. These cases have occurred after the women are found in police raids.

The Counter Trafficking Unit (CTU), created in 2013 to investigate and prosecute human trafficking cases and also to provide assistance to the victims, is not, however, immune to accusations. Lack of investigation, follow-up and even abandonment of cases, precarious conditions in shelter houses, lack of psychological care to victims, and little transparency in resources, are some of the complaints that activists and trafficking victims make about this office. Since 2017, CTU has not reported its budget, based on a report by the U.S. State Department, although there is an evident drop in the allocation of resources for victims.

Reina experienced the shortcomings firsthand. Although she reported to CTU that she was kidnapped, drugged and raped, her case fizzled out, she says. After four months of statements, in which she and another victim of the same criminal group gave the name of their captor, nicknames of the criminal gang and even photos, officials of this institution told her that they did not consider her a victim and, thus, there was no open case. They had to leave the protection house where they were staying.

This journalistic team requested an interview with Alana Wheeler, director of CTU, to verify these claims, but she said that she is not authorized to give statements.

Deportation, without police and judicial resolution of the cases, is often the fate of Venezuelan women once they leave the trafficking networks. An official document, which the journalistic team had accessed to, described the passengers of a “humanitarian flight” to Venezuela in late 2020, and contained information about an 18-year-old victim who was repatriated.

Different organizations handle information about at least six other adolescent victims of sexual exploitation, who were deported - one of them pregnant - in the first months of 2021. Lilia, the 17-year-old teenager taken in Maturin, was repatriated at the beginning of the year, after having spent 13 months in a detention center for adolescents and in the home of a foster family.

Reina affirms that her complaint was not only abandoned, but also manipulated. “I told them everything that happened. That he (her captor) acted aggressively when he drank or took drugs, and that, on one occasion, he pulled a gun on me to make me have sex with him. But then I was able to read that CTU wrote in the file that I voluntarily had sex with him every day. It was nuts,” she says. In the end, Reina was also deported to Venezuela.

(*) The names identified in this report with an asterisk have been changed for security reasons.

**This story was written by Marielba Núñez and Claudia Smolansky for Armando.Info and CONNECTAS, with the support of the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) in the framework of the Investigative Journalism Initiative of the Americas.

Six out of every ten Venezuelan sex workers killed abroad since 2012 were in Mexico. In that country it is often about attractive girls who work as high-level company ladies or night-time waiters, businesses directly managed by organized crime. There are many clues that lead to the Guadalajara New Generation Cartel at the peak of this trade in people, with the complicity of others such as Los Cuinis and Tepito. Often the human merchandise becomes the property of capos and assassins, with whom he knows the hell of the femicides

Since the borders to Colombia and Brazil are packed and there is minimal access to foreign currency to reach other desirable destinations, crossing to Trinidad and Tobago is one of the most accessible routes for those in distress seeking to flee Venezuela. Relocating them is the business of the 'coyotes' who are based in the states of Sucre or Delta Amacuro, while cheating them is that of the boatmen, fishermen, smugglers and security forces that haunt them.

Without human rights officers at the ports of entry or legal system that protects the refugee, Venezuelans migrating to the Caribbean island find relief from hunger and shortages. In return, they are exposed to labor exploitation and the constant persecution of corrupt authorities. On many occasions they end up in detention centers with inhumane conditions, from which only those who pay large amounts of money in fines are saved. The asylum request is a weak shield that hardly helps in case of arrest. Yet, the number of those who try their luck to earn a few dollars grows.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.