Far from Cuba, the Venezuelan identity documents were actually designed in Germany. Havana’s intermediation has only left a trail of transfers and commissions that transited at least four countries. For years, there was a surreptitious key character in this operation. But his secret was not kept under lock and key, and is about to be revealed in this report.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

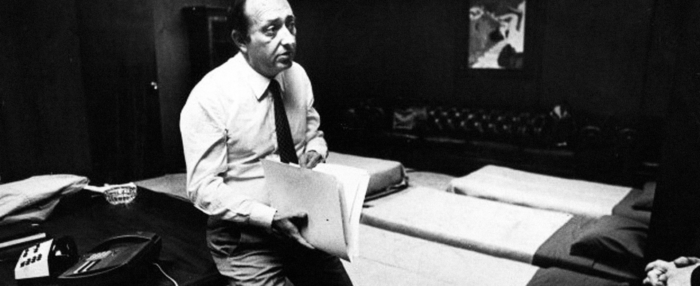

Clinging to his equity, Peruvian banker Francisco Pardo is remembered in Lima for having hidden - with a mattress and everything - in his office of Banco Mercantil, which no longer exists in Peru. "There is no negotiation with nationalization," he declared in 1987 against the decree that President Alan García had issued to nationalize the bank. Who would say that the same person who 30 years ago broke spears and tended mattresses in Peru for private property, is now behind a network of companies that allowed Fidel Castro's Cuba to provide the passports of Hugo Chavez's Venezuela?

Francisco Javier Pardo Mesones, or "Pancho", as he is also called, chaired the Association of Banks of Peru in the 80s, and in the following decade, he was in the Congress of the Republic, first as parliamentarian of the party of the former secretary of the United Nations, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, and then, on the other side of the floor, in the ranks of Alberto Fujimori.

Great grandson of the first civilian president of that country, his name is among the honorary members of an elite that has been meeting for 160 years in the legendary National Club of downtown Lima.

For 15 years, Pancho Pardo was far from the commotion of public life, but, like when he hid in his office to avoid expropriation, he is back at the front page. The documents kept - and now leaked - in the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca point him out as the true beneficiary of Billingsley Global Corp and other offshore companies, which served as a vehicle for Havana to resell the technology of Bolivarian passports to Caracas.

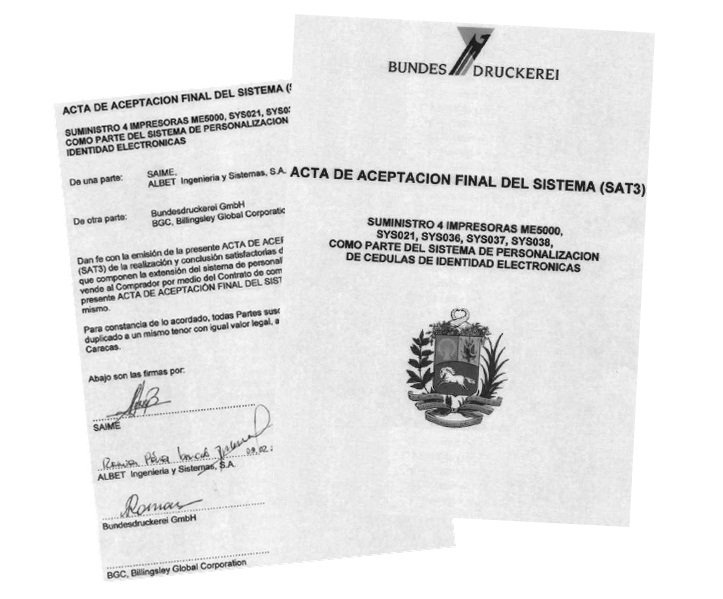

The polycarbonate sheets of the identity documents actually came from Germany, from company Bundesdrukerei. "This company does not want to sell directly to Cuba and Venezuela, mainly because of the reputational aspect. They fear that the competition makes adverse propaganda on the matter of sales to totalitarian governments."

Lawyer Ramsés Owens, by then, one of the senior executives of the law firm, noticed that in an internal correspondence over eight years ago, on November 26, 2007. "Fortunately for us there is nothing that inhibits us in Panama," he said in the same email.

Chavez government began to renew its identification system in late 2005. Hence, the then Minister of Interior and Justice, Jesse Chacón, was commissioned to look for some of the technology giants to first produce the new passports and then the so-called electronic ID cards announced since then. The US companies were discarded at once and the Chinese preferred to pass by due to the Cuban intermediation. This is how Pardo Mesones set up in Caracas a triangulation of transfers and contracts through tax havens.

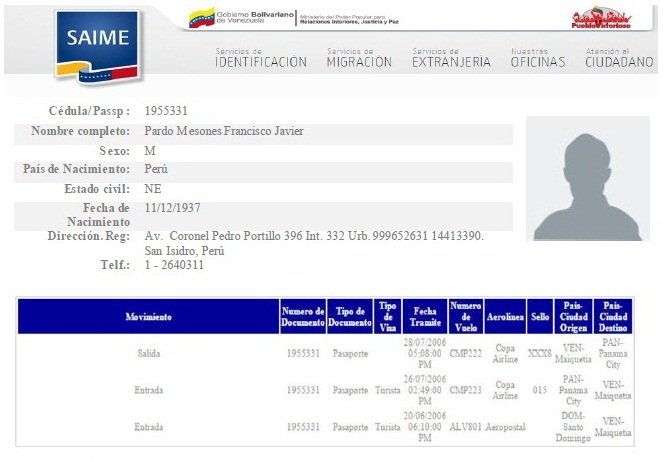

Based on immigration records, Pardo Mesones arrived in the Venezuelan capital on July 26, 2006, at 2:49 PM, on flight 223 of Copa Airlines and flight back a couple of days later after a negotiation in which, according to the database of the Administrative Service of Identification, Migration, and Immigration (Saime), he coincided in Venezuela with the German Joerg Baumgartl, who was the head of company Bundesdrukerei.

The rest of the business was coordinated between Lima and Panama City, in the offices of Mossack Fonseca, the staff of which designed a “financial bicycle” that enabled the triangulation. Just two weeks before the visit to Caracas, Pardo Mesones had chosen the name of the company from a list of three turn-key law firms recently registered in Panama and ready to be used. "The client wants to acquire company Billingsley Global Corp," the representative of the law firm in Lima, Mónica Ycaza, wrote on July 11, 2006 to her co-workers at the headquarters.

In Panama, they concluded the coordination of the process and even opened the bank accounts where the first deposits from Havana arrived. Pardo Mesones had provided one of the best business cards for that purpose, a reference letter signed by Pedro Pablo Kuczysnki, the then second leader in the government of Alejandro Toledo and current candidate with options to win the Presidency of Peru in the second round.

"I am pleased to introduce Mr. Francisco Pardo Mesones, who is an old acquaintance of mine, an honorable and well-known man in Peru," Kuczysnki wrote in the letter, stamped in June 2006, with a letterhead of the Peruvian Council of Ministers. Now in campaign, he warns that the letter was a plain formalism. Pardo and Kuczysnki were peers in the classrooms of Markham College in Lima. But there are no close ties, says the presidential candidate. "Now I see him sporadically," he says. "I have signed many such letters. In many cases, I was asked to write letters of introduction for Peruvian professionals, and I did it with pleasure."

With these references, in any case, and the contracts signed with Cuba and Venezuela, the newly created company Billingsley Gobal Corp secured at least 64 million euros for itself: 40 million had to reach Germany and the other 24 would stay with Pardo in Panama, as Owens warned in another email to Sascha Haust from the German bank Dresdner Bank AG. But, even so, it was not easy to find international banks that accepted the letters of credit from Banco Financiero Internacional of Cuba as collaterals, as it is affected by the still effective economic blockade imposed by the US government on the entire Cuban economy.

In Panama, Credicorp and Multibank opened the first accounts for Billingsley. The most difficult thing was to find other key players acting as extras in Europe to finish triangulating the journey of some transfers from Venezuela to Germany.

Owens and the rest of Mossack Fonseca's team knocked on the doors of BBVA, Berenberg Bank and Dresdner Bank AG. They even appealed to the Republic Bank Limited of Trinidad and Tobago, which – in his own words - has been able to take advantage of the embargo against Cuba to pay its cash bills in exchange for unprecedented commissions ranging between 10% and 20%. "Basically, the government of Cuba is a client of this bank." He says in a string of emails that they were looking where to keep the money. "Anyway, this is a bank that deals with Cuba, and may have ideas and solutions for our friend Pardo Mesones :)."

Venezuelan passports have been issued in this way in the shadow of absolute secrecy. The negotiation - until now kept secret - establishes express confidentiality clauses, and not in one or two, but in all contracts. Even in the following phases, as it can be read in “Contract I10-084-000/2010 for the expansion of the passport and electronic identity card personalization system for the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela".

Cuba also reserved access to the software through Albet Ingeniería y Sistemas, the subsidiary that the Castro regime designed exclusively for this task. "Albet will acquire a perpetual, non-exclusive and non-transferable right of use through the software provided together with the system," the document states.

Computer engineer Anthony Daquin had already warned that - after reporting the case - he went from being an advisor to the Ministry of Interior and Justice to an asylee in the United States of America. "The Cubans manage the software and set the security guidelines," said journalist Adriana Rivera in the July 20, 2011 issue of the newspaper El Nacional, in a report that gave for the first time news about the hand of Cuba in the Venezuelan identification system.

"The originals of the source codes (those describing the operation of the software and allowing changes to be made) of the developed computer applications will be kept by the Cuban side while the technical support period remains in effect," he said at the time. Today he says from the USA that nothing has changed. "These people have the capacity to issue a Venezuelan passport in Cuba and set up the data in the system at the same time."

To Daquin, it is no accident that Caracas became one of the most dangerous cities in the world just when the Venezuelan Government interconnected the civil registry with tax and commercial information. "The organized crime is using the system to kidnap!" He exclaims on the other side of the phone. But even if that were not the case, there is no doubt that the burgundy passports were so expensive that they made it possible for a series of transfers and commissions from Havana to the anything but socialist law firm Mossack Fonseca.

It was precisely in the offices of Mossack Fonseca where they always took care to keep under lock and key the intricacies of this operation. Even Pardo Mesones’ résumé remained there, where it is evident that already in the 70s he was no alien to Venezuela, where he started a career in the insurance market leading the Association of Insurers of Venezuela, La Unión Compañía de Seguros (insurance company) and the local office of American International Underwriters.

The Panamanian law firm also kept a copy of his passport. Despite all these evidences, Pardo Mesones categorically denied his participation in this story. "I do not know what you are talking about," he answered this week by phone in Lima. "I cannot meet with you because I do not know what you are talking about. I am a 78-year-old man, I am retired and I do not want to know anything about the Prosecutor's Office or strange things."

Moderate and cautious, Pardo Mesones had left no traces since 2006. When he opened the company, he asked for the documents not to be sent to Lima and, in just in case, he requested through his agents for the registration to be with "bearer shares," a legal concept that in Panama allows anonymity to be kept under a title that guarantees ownership to anyone who has it in their hands. Something like a traveler's check.

Billingsley was a kind of ghost, which could only sense some lights when someone had to sign on its behalf. In 2008, it registered special powers of attorney for Pardo Mesones and his partners in the Bundesdruckerei, the Germans Joachim Gerhard Kammerer and Joerg Baumgatl, the same who, under affidavit of April 3, 2014, denied having had personal links with Billingsley Global Corp.

Two years later, Mossack Fonseca put an additional reserve lock when placing lawyer Ricardo Icaza Huertas at the head of the company, whose name stands out in the Public Registry of Panama in charge of over 230 companies. At the same time, the fictitious owner guaranteed the shares to the real owner through a trust of the shares.

But Caesar's wife must be above suspicion. Jealous that its own seemed like another briefcase company, the law firm implemented in Billingsley a telephone service number +511 965-2631, as part of another of its products, the "virtual office" service, with a rate established at $ 45 for each email or phone calls attended.

"Good morning, Billingsley Global Corporation, what can I do for you?" the recording said. Then, it was the turn of a bilingual operator to whom the name of Francisco Pardo Mesones was written under an item dedicated to specify the "Details of the effective owner (true owner)." Billingsley also promoted itself on the Web, through the Google Ads advertisement service. The invoice of the transaction was registered with code GG11/PA/00867988/00002157 in the name of Francis Pérez, another Mossack Fonseca employee, who, even before this case, had already been mentioned in other countries for being on the board of directors of companies such as Helvetic Services Group and Cifart, investigated for corruption scandals in Argentina and Paraguay, respectively.

Most of the money finally arrived in Europe, but in parts. While there are powers of attorney and invoices that involve Bundesdrukerei in this scheme, its director, Joerg Baumgartl, always took care not to appear in public. But he forgot to take into account that his father-in-law, Peruvian Miguel Arbulú Alva, not only represented the German company in Peru, but as stated in his résumé, he held key positions in the business consulting firm Exxed, founded by nothing less than Pardo Mesones.

Baumgartl also forgot that even though he was hidden in the Caribbean, his name was registered along with Pardo Mesones, not in Billingsley Global Corp of Panama but in Billingsley Global Investments Corp of the British Virgin Islands, better known as a tax haven than for its beaches.

The same Peruvian and the same German who met in Caracas in July 2006, were united a year later -on June 13, 2007- in a society in which both of them gave the address of La Molina de Lima, Calle La Vuelto 145, Rinconada Alta, where Pardo Mesones lives, as their domicile.

As if it were about Russian dolls, the weekly news magazine Der Spiegel, published in Hamburg warned in its February 20, 2014 issue, that the same Bundesdrukerei that manufactures the German passports and a most of the euro zone banknotes was part of a web of companies within companies, also of Latin American bribes and commissions. That day, they published the name of Billingsley. Now the company did not only appear in Google Adds, but in "a money laundering play."

Based on the testimony of a former Bundesdruckerei broker in Venezuela to Der Spiegel, there were two other offshore Panamanian companies, Selbor and Sotelco, created at the request of Baumgartl, which corresponds to the new data obtained. In Mossack Fonseca's communications there is an invoice from Sotelco of more than half a million euros, for "data capturing" services provided to Billingsley Global Corp.

Baumgartl sued Der Spiegel before the Court of Cologne specializing in press matters, the same that gave the green light to the weekly news magazine to continue writing about the subject.

Although the name of Pardo Mesones did not appear in that first issue of Der Spiegel, the alarms in Peru triggered quickly. In less than a month, the Peruvian was in Panama doing damage control. "It is because of a publication of the German news magazine Der Spiegel about Billingsley," confirmed Mossack Fonseca's representative in Lima, Mónica De Icaza, in an email on her client's trip.

The decision was to revoke the powers of attorney issued to Bundesdrukerei’s representatives. "Following your request, please find attached drafts of the revocation records of the Powers of Attorney issued to Joerg Baumgartl, and the draft of the Special Power of Attorney issued to Joachim Gerhard Kammerer, all dated retroactively." So, at least on paper, this story would never have happened if the dam that kept the millions of secrets of Mossack Fonseca had not collapsed.

(*) This is a team work simultaneously documented and published by Armando.info in Venezuela and IDL-Reporteros in Peru, in the course of #PanamaPapers.

Pequiven, a subsidiary of Petróleos de Venezuela, sought shelter in tax havens to legalize its association with Iranian company National Petrochemical Company, from which Veniran emerged. Although the Panamanian law firm was suspicious of the alliance between the then presidents Hugo Chávez and Mahmud Ahmadinejad, it finally solved the inconvenience to please both clients.

Leonardo González Dellán headed Banco Industrial de Venezuela (BIV) from 2002 to 2004. The papers of Mossack Fonseca reveal that, in this period, which also coincided with the establishment of the exchange control and the birth of the extinct Cadivi, he was related to overseas companies.

The last two major global investigations conducted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists revealed the offshore business of Eligio Cedeño, a former Venezuelan banker considered a fugitive from justice by some and politically persecuted by others. Company Cedel International Investment, owner of Bolívar Banco and Banpro, also requested the services of Mossack Fonseca to operate in the British Virgin Islands.

The name of the former head of the Venezuelan oil company in Colombia appears in the papers of Mossack Fonseca with 100% of the shares of a company created in June 2011, of which she requested to be dissolved six months later. She is unemployed since August 2015, when she was replaced by the ex-sister-in-law of President Nicolás Maduro

The so-called "insurance tsar" opened four offshore companies in a Caribbean island through the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. Corporación OFL, which consists of about 20 companies in his name, makes him one of the entrepreneurs in the insurance sector that has grown the most during the chavista government.

The ex-banker used the services of the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca to register companies in tax havens while he was being tried in Venezuela by his ex-colleagues from the Stanford Group. He said he was a victim of chavism to be accepted as a client and thus protect his fortune.

When Vice President Delcy Rodríguez turned to a group of Mexican friends and partners to lessen the new electricity emergency in Venezuela, she laid the foundation stone of a shortcut through which Chavismo and its commercial allies have dodged the sanctions imposed by Washington on PDVSA’s exports of crude oil. Since then, with Alex Saab, Joaquín Leal and Alessandro Bazzoni as key figures, the circuit has spread to some thirty countries to trade other Venezuelan commodities. This is part of the revelations of this joint investigative series between the newspaper El País and Armando.info, developed from a leak of thousands of documents.

Leaked documents on Libre Abordo and the rest of the shady network that Joaquín Leal managed from Mexico, with tentacles reaching 30 countries, ―aimed to trade PDVSA crude oil and other raw materials that the Caracas regime needed to place in international markets in spite of the sanctions― show that the businessman claimed to have the approval of the Mexican government and supplies from Segalmex, an official entity. Beyond this smoking gun, there is evidence that Leal had privileged access to the vice foreign minister for Latin America and the Caribbean, Maximiliano Reyes.

The business structure that Alex Saab had registered in Turkey—revealed in 2018 in an article by Armando.info—was merely a false start for his plans to export Venezuelan coal. Almost simultaneously, the Colombian merchant made contact with his Mexican counterpart, Joaquín Leal, to plot a network that would not only market crude oil from Venezuelan state oil company PDVSA, as part of a maneuver to bypass the sanctions imposed by Washington, but would also take charge of a scheme to export coal from the mines of Zulia, in western Venezuela. The dirty play allowed that thousands of tons, valued in millions of dollars, ended up in ports in Mexico and Central America.

As part of their business network based in Mexico, with one foot in Dubai, the two traders devised a way to replace the operation of the large international credit card franchises if they were to abandon the Venezuelan market because of Washington’s sanctions. The developed electronic payment system, “Paquete Alcance,” aimed to get hundreds of millions of dollars in remittances sent by expatriates and use them to finance purchases at CLAP stores.

Scions of different lineages of tycoons in Venezuela, Francisco D’Agostino and Eduardo Cisneros are non-blood relatives. They were also partners for a short time in Elemento Oil & Gas Ltd, a Malta-based company, over which the young Cisneros eventually took full ownership. Elemento was a protagonist in the secret network of Venezuelan crude oil marketing that Joaquín Leal activated from Mexico. However, when it came to imposing sanctions, Washington penalized D’Agostino only… Why?

Through a company registered in Mexico – Consorcio Panamericano de Exportación – with no known trajectory or experience, Joaquín Leal made a daring proposal to the Venezuelan Guyana Corporation to “reactivate” the aluminum industry, paralyzed after March 2019 blackout. The business proposed to pay the power supply of state-owned companies in exchange for payment-in-kind with the metal.